Review: Imax documentary ‘Apollo 11’ is a virtual round-trip ticket to the moon

One of filmmaking’s cheapest tricks is on-screen applause – where characters clap to cue the movie’s viewers that they should also be impressed. There’s a lot of that in “Apollo 11,” but it’s not cheap. In this documentary about the people who pulled off the spectacular feat of sending Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins to the moon in 1969, the ovations are genuine, spontaneous and well deserved.

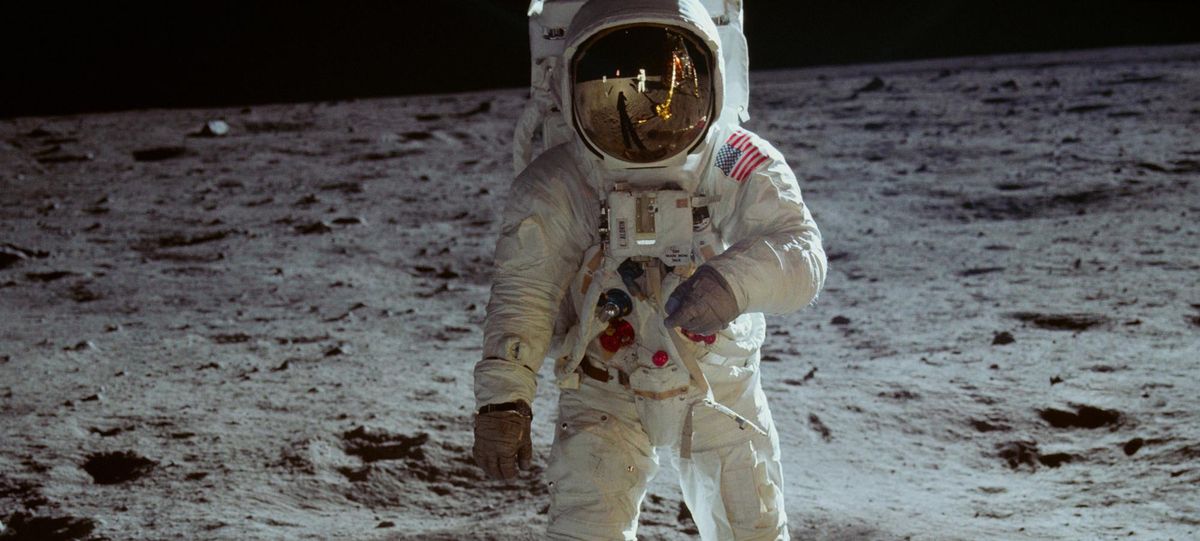

NASA’s first lunar landing is not exactly an obscure event. And “Apollo 11” doesn’t profess to offer new information or insights. What it does offer is a wealth of fresh images and sound, assembled into an immersive Imax journey by director and editor Todd Douglas Miller. It’s a more visceral trip than any moviegoer – even the armchair experts – has ever taken before.

It was inevitable that some movie about the first moon landing would be released in 2019, the 50th anniversary of Armstrong and Aldrin’s stroll on the lunar surface. But Miller’s documentary still packs surprises because in the buildup to that anniversary, a momentous discovery was made at the National Archives: a hoard of never-developed film from the Apollo 11 mission was unearthed, some of it in 70 mm. The filmmakers also made use of a bounty of audio material whose existence was previously known but which had never before been synced to pictures.

In “Apollo 11,” Miller combines the newly excavated footage with some that’s been seen before, but only in a cropped, 35mm format. Some of the found film is not as crisp as contemporary digital imagery, but it has an immediacy that today’s CGI-dependent tales of cosmic fantasy never achieve.

There are no voice-over commentaries here, no talking-head interviews or TV news clips. We hear Walter Cronkite, the Homer of the American space odyssey, but we never see his face. Other than the astronauts, the celebrities, including Johnny Carson, are reduced to spectators, sweltering in Florida’s July heat along with everyone else, as they wait for liftoff – and a glimpse of the day’s real stars.

The emphasis is on workaday procedure, not giant leaps. “Apollo 11” tells the story by an accumulation of small details: a rig in motion; a leaky valve; Aldrin’s heart rate; snippets of flight data and diagrams superimposed on the screen. Close-ups of text-only computer monitors and pencil-on-paper calculations reveal the project’s reliance on human smarts and dedication. Ordering a pair of socks online today involves more computing muscle than NASA had in 1969.

But there’s a paradox: The movie becomes more ordinary during the sequences that were, in reality, the most extraordinary. Once the Apollo 11 module reaches space, all the available images are taken from photos and films that have been seen before. The astronauts’ sojourn on the moon itself is told mostly with a sequence of still photographs. Things heat up again as the crew heads home, and the number of locations and camera angles increases, dramatically.

Another source of drama is Matt Morton’s music, which throbs and pulses – before turning, unfortunately, a little too honeyed at the end. In the spirit of the era, Morton used only analog synthesizers that were available in 1969. Like the engineers who somehow managed to send a man to the moon in the pre-PC era, Morton’s score makes the most of its technical limitations