This column reflects the opinion of the writer. Learn about the differences between a news story and an opinion column.

Less than 13 years into a 20-year sentence, family of Linda Strait is fighting to keep her killer behind bars

On a May afternoon in 1983, a man asked two 8-year-old girls outside Trent Elementary to help him look for the keys to his car.

He then pushed the girls into the car and drove off. One of the girls escaped; the other was raped and choked repeatedly, then left for dead in a wooded area.

The girl had not died, though. She rose and went for help, and the man was eventually sentenced to prison for kidnapping and rape. Twenty-three years later – as the man was about to go before the parole board – she found herself sitting in a courtroom with her attacker, Arbie Dean Williams.

“To come in contact with you is to lose a part of your soul,” she said. “Not even death is good enough for you. You can’t look at me now, can you?”

She was not testifying in her own case, but in a long-unsolved murder Williams had committed not long before he had kidnapped her at Trent. The rape and murder of 15-year-old Linda Strait had been a long-unsolved mystery in Spokane, one that had tormented Strait’s family and frustrated investigators.

After more than two decades, a DNA match proved he was Strait’s killer, as well.

As he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, Williams told the judge he didn’t expect the family to forgive him.

“I don’t see how you could forgive a person like me,” he said.

In April, Williams will go before the parole board once again, having served less than 13 years of his sentence. As Williams foresaw, forgiveness was not forthcoming from the people whose lives he shattered, not then or now.

Strait’s family is working to persuade the members of the board that not only should Williams not be released now – he should not be released at the end of his full sentence, either. He should never be released, they say, and given the nature of his crimes it’s possible the state could commit him civilly as a sexual predator after his criminal sentence is served.

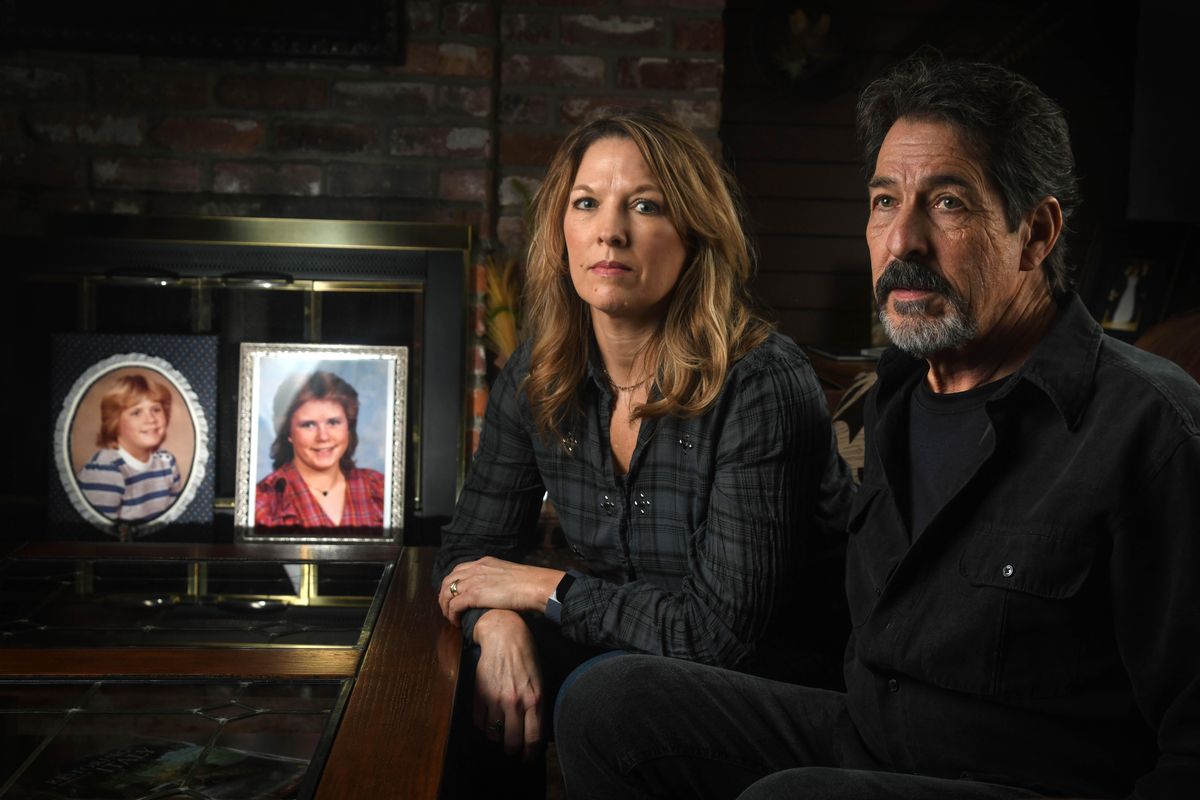

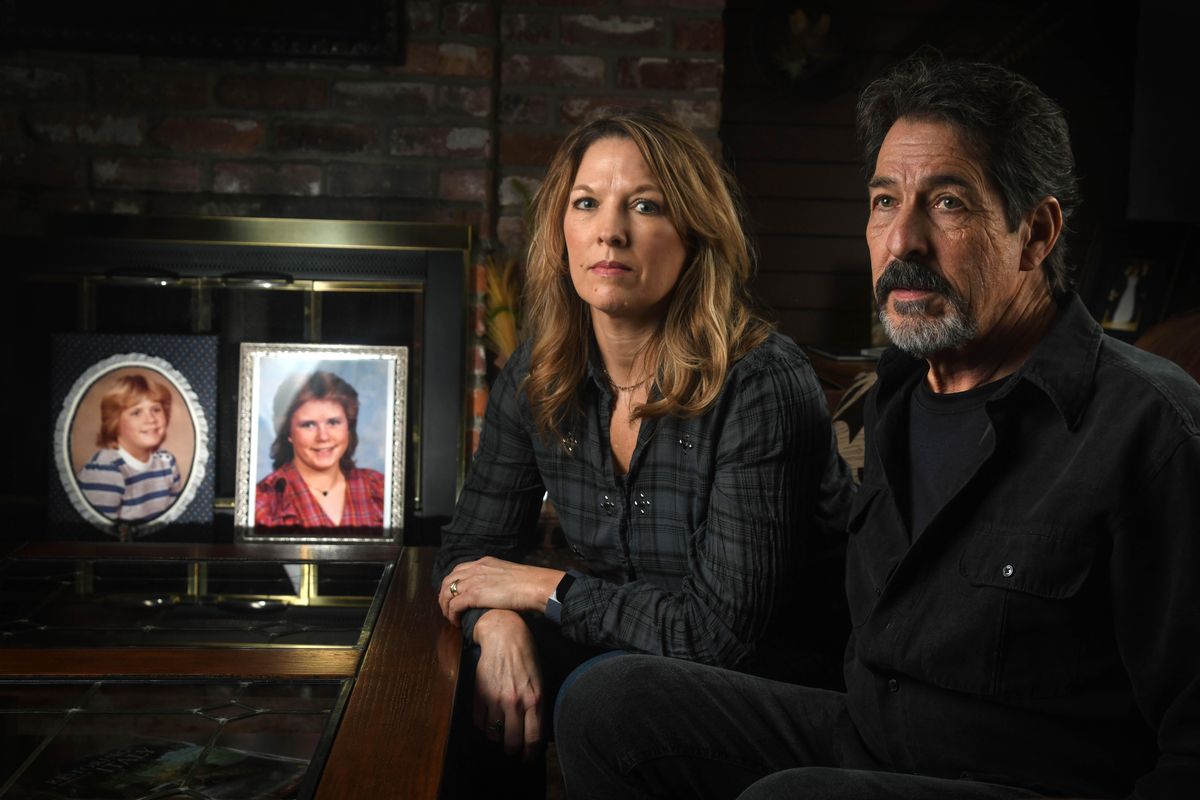

“I had the assumption that he’d be in for life,” said John Milla, Linda’s cousin. “How do you not get life for doing what he did?”

‘Full of life and spirit’

In the early 1980s, Theresa Milla, her sister, Mary, and their cousin Linda Strait spent their summers constantly in each other’s company. Theresa, Mary and John were part of a large family of seven kids who lived in the Spokane Valley; Linda lived on Spokane’s North Side with her family.

At the Millas’ house, the teenagers would pull weeds, snap beans and do the other chores they were assigned, and then they’d walk to Valley Mission Park, about a mile away, to swim and play. Or they’d sit outside and play board games until it got dark, or go to basketball camp together.

“We were inseparable,” said Theresa, whose surname is now Briggs. “We never got tired of each other.”

Linda was a sophomore at North Central High in 1982, with interests in basketball and playing the flute, roller-skating and video games.

“She was just so smart, so sweet, so full of life and spirit,” Theresa said.

When they were at Linda’s house in Spokane, it was common for them to walk to a nearby Safeway about a quarter-mile away.

On a Sunday in late September 1982, Linda walked by herself to that store around noon and never returned. The following day, her body was found in the Spokane River. She had been suffocated and raped; among the items found on her body was a pillowcase with her attacker’s semen.

The search for her killer dominated local news for weeks. TV cameras lined the back of her funeral. Her stepfather, George Ragland, did press interviews and tried to keep bringing public attention to the case. Investigators interviewed nearly 1,000 people, including several potential suspects, but no leads panned out.

Six months after her murder, Ragland told The Spokesman-Review, “I stand at Linda’s grave and wish she could say just two or three words. I spend a lot of time there. And I look, and I think, and I wonder.”

Time passed without an arrest. The local news stories became less frequent, dwindling to the occasional anniversary remembrance of the horrible, unsolved case.

At one point, there was speculation that she might have been the victim of the Green River Killer – an idea that her parents publicly resisted, because most of the victims in that case had led troubled lives. It was a time when police believed that the state had a significant number of unsolved killings – around 50 – they believed “aroused suspicion of being victims of serial killers,” according to one official with the attorney general’s office in 1985.

In 1990, detectives released new information about the case in a bid to jar something loose – an embroidery pattern from a pillowcase that had been found on Strait’s body, and other details. Strait’s parents offered a $10,000 reward for information leading to an arrest.

“We’re just baffled by this one,” said Mike Massong, one of the sheriff’s detectives investigating the case.

Science catches up

In 1998, then-detective Tim Hines was assigned to the case for the Sheriff’s Office. Among the evidence he noted in the case was the DNA evidence of the attacker.

Nine years earlier, that evidence had been insufficient to provide a DNA profile of the killer. But the science had advanced greatly in the intervening years. As investigators began to press to use DNA technology to try and solve cold cases, the Spokane County Board of Commissioners approved expanded funding for such testing in 2002.

In April 2003, Hines submitted a partial DNA sample to the state crime lab; because it was so old, the sample was partially degraded, and it wasn’t certain that it would work, according to a summary of the revelation from the sheriff’s office at the time. But the sample was checked against a database of convicted felons, and a match was found: Arbie Dean Williams.

Williams was incarcerated at McNeil Island Correctional Institute, approaching a parole hearing for his 20-year sentence in the abduction and rape case from 1983.

In part to spare the family a long trial, a plea deal was struck; Williams would plead guilty to second-degree murder and be sentenced to 20 years, after which the state would determine whether he would be released or civilly committed as a sexually violent predator.

The day of his plea and sentencing – July 31, 2006 – was one of great confusion and drama. Williams pleaded guilty, then tried to rescind the plea as the judge began describing his crime, then went ahead with the guilty plea.

Linda’s family members packed into the courtroom. And her mother, Donna Ragland, testified just as the woman who Williams had raped as a child had done, speaking to him directly and forcefully.

“I think you are the scum of the earth and I hope you rot in hell,” she said.

‘We were so innocent’

On Feb. 4, Donna Ragland received a letter from the state Indeterminate Sentencing Review Board, saying that Williams had a hearing on a potential release coming up in April.

Ragland, who did not want to be interviewed for this story, was astounded, John Milla said. Her husband, George, had died in recent years.

“Our aunt is 86 and like all of us we thought that this was in the rearview mirror permanently,” he said. “This knocked her off her axis.”

Milla said his family had simply assumed that the sentence would be for life. Williams was 62 years old at the time – he’s now in his mid-70s. Even though Milla understands that what’s happening is the way the system works, and that the fact Williams is having a hearing doesn’t mean he will be released – it’s hard to swallow the idea that someone who did what Williams did, to Linda and to the girls from Trent Elementary, might go free.

“It’s been a sad, sickening education,” he said.

Milla and Briggs have taken it upon themselves to rally a campaign to urge the Indeterminate Sentence Review Board to keep Williams locked up. The board has the authority to make recommendations for extended civil commitments for sexually violent predators who have completed a criminal sentence.

But that would happen later. Now, as a part of their preparations for the April hearing, Briggs has set up a website (justiceforlindastrait.weebly.com/) and a Facebook page devoted to the case.

The Facebook page is a testament to the enduring memory of Linda and what happened to her. Comment after comment reinforces how powerfully Linda’s life and death continues to resonate with people here.

“I will never forget the night I stayed up until 11 watching the news to make sure it wasn’t Linda …”

“Linda was a friend and sports teammate … her smile was contagious …”

“If there’s anything I can do to keep that killer off the street, let me know …”

“That happened in my neighborhood. It just never leaves your mind or memory.”

Family members will meet with members of the parole board before the hearing. They’re urging people to write the board and ask them to keep Williams incarcerated. So far, they say, more than 30 letters have been written.

It’s another chapter in a story that seems to never end for the family of Linda Strait – one that has often put them in the public eye as they delve once more into the painful details.

Briggs, who was 14 at the time of Linda’s death, said it marked her life ever after.

“It shattered our lives,” she said. “We were so innocent back then. It took away the innocence and made me aware of every step I take outside a safe space.”

She carried that sense of caution and protectiveness into the way she raised her now-grown daughter.

“I told her I’m sorry, I’m never going to stop,” Briggs said. “You need to be aware there are evil people out there.”