Decades after a divisive groundbreaking, the Thomas S. Foley U.S. Courthouse ‘building is wholly Spokane’

The clock on the ninth floor of Spokane’s Thomas S. Foley United States Courthouse is part of the wall – embedded when the building was constructed in 1967.

It used be part of a centralized clock system, with a master clock in the basement keeping time for its many servants around the building. But too many people jiggered with its arms and now the ninth floor clock is battery powered and protected by a plastic shell.

Paul Zambon, field office manager for the local region of the U.S. General Services Administration, tells this story as part of another, itself embedded in the history of the building. Built 52 years ago, and characteristic of midcentury modern architecture, the building was recently deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places, and the GSA is going over the interior of the building to determine the historical significance for each area, from elevator lobbies to courtrooms.

Made of 850,000 bricks cast from local clay deposits, designed by local architects and built by local laborers, the building is wholly Spokane – even if it represents “the federal presence in Spokane,” as Zambon said.

Its shape is reminiscent of the Parkade, which was built just a year earlier, and its color and masonry like the muted tone and construction of the turreted Spokane Regional Health Building. But it came from D.C., which mandated “efficient and economical facilities” that provided “visual testimony to the dignity, enterprise, vigor and stability of the American Government” as laid out in federal building guidelines in 1962.

Zambon, who called the GSA “the landlords for the government,” was less comfortable detailing historic facts about the building than speaking of its efficiency.

“I like mechanical spaces. Boilers and chillers. Things like that,” he said. The modern heating and cooling system, installed in 2012, makes its low energy costs “the pride of the nation.”

When the Modernist courthouse opened in 1967, it wasn’t exactly the pride of Spokane. While lauded for its potential to help rejuvenate the city center, it was nearly immediately criticized for its design. The intervening five decades, however, have proven its steadiness on the Spokane skyline, with its flared cornices ringing the building’s roof, basket handle archways at ground-level and seemingly countless tan bricks pulled from the Mica brickworks southeast of the city.

As opinions soften toward the sometimes severe, concrete-friendly architecture of the mid-20th century, the federal courthouse is ready for its day, said Rebecca Nielsen, regional historic preservation officer for the regional GSA.

Calling the building an “iconic civic structure,” Nielsen said in a statement, “It’s a great addition to Spokane’s growing collection of Modernist buildings.”

New courthouse, no Ebasco

On June 8, 1961, the Spokane Daily Chronicle broke the news: The old federal courthouse on Riverside Avenue no longer had adequate space. Numerous federal agencies were spread around town in 15 different commercial locations, and a large building had to be built to fit them all.

No site had been chosen, but Mayor Neal Fossen suggested it be built concurrently with a new City Hall. “I’m thrilled; it’s wonderful,” he said. “This ties in beautifully with our proposed governmental center site.”

City leaders were deep into plans to remake downtown following the midcentury ideas of “urban renewal,” which meant demolition and reconstruction. The so-called Ebasco report guiding the plans envisioned a “Civic Center” with city, county and federal buildings in “one complex near the business core of the city,” according to a October 1961 Chronicle article.

The GSA was on board, and so were lawmakers. On June 14, 1961, the House Public Works Committee approved the $8.7 million needed for the Spokane federal building, and a few weeks later, the Senate appropriations committee devoted $1.5 million to acquire property.

Newspaper reports were unclear on where Ebasco’s government center was planned. Some said the block bounded by Stevens and Washington streets, Main Avenue and the former Trent Avenue now called Spokane Falls Boulevard, where Auntie’s Bookstore is located. Others pointed to the block held by the Davenport Grand. One said the Realty Building near Bernard Street. Regardless, GSA officials said the Civic Center site was a “primary consideration.”

Voters had a different idea. On March 13, 1962, they turned down a $10.4 million bond that would’ve funded the Ebasco report’s plans. It needed 60% of voters to approve it, but only got 40%. The rebuke by voters shocked the city’s political leaders. But federal officials said a new courthouse would still be built, just not where Ebasco said it should be.

“There is definite need for such facilities in Spokane,” said H.A. Abersfeller, regional director for GSA. “However, no one can say now where the new building may be located.”

Abersfeller said it would probably be better to build a new courthouse near the existing one on Riverside Avenue near Lincoln Street, now the U.S. Post Office.

The month after the vote, GSA said it had found a new site: “the north half of the block bounded by Monroe, Riverside, Madison and Sprague.”

City leaders, fresh from defeat by voters, reacted against the new site. Fossen, the mayor, asked GSA to postpone a final site decision. Councilman Del Jones said the new site would lead to “destroying a beautiful building,” referring to the still-standing Western Union Life Building.

Abersfeller dismissed Fossen and Jones, saying the project could not be delayed.

“Any further delay would, in my opinion, seriously jeopardize the building itself,” he said. “We would have considered the eastern downtown site if the Urban Renewal plan had developed. But I find it difficult to recommend that a federal building be placed in a blighted area when there is no guarantee of rejuvenation.”

S-Double A-C, serpentine curve

Somehow, someway, the GSA began “having some second thoughts” about the site and were considering the site adjacent to the post office, according to a July 1962 article in the Chronicle. Unlike the Western Union Life Building, designed by Kirtland Cutter and expanded by Gustav Pehrson, the buildings standing at the new location had no advocates in government.

At the time, the site had the YWCA facing Main, and facing Riverside was the Dodd Block, which contained “several first-floor offices, plus apartments on its two upper floors.”

In September 1962, it was official. The Chronicle ran a story with the headline, “Dodd Block Job Tops $8 Million.”

The next spring, two local architecture companies were given a joint contract on the building, Culler, Gale, Martell, Morrie & Davis, and McClure, Adkison, Walker & McGough. By year’s end, in December 1964, The Spokesman-Review revealed the plans for the courthouse. It was to be a “nine-story structure facing a landscaped quarter-circle forecourt 140 feet deep.” Riverside would be realigned “to create a continuous curve of constant radius.” The building will be “light-colored brick harmonizing with the color of the existing Post Office Building” and an “arcade will surround all four sides of the building on the ground level with arched openings in the outer wall.”

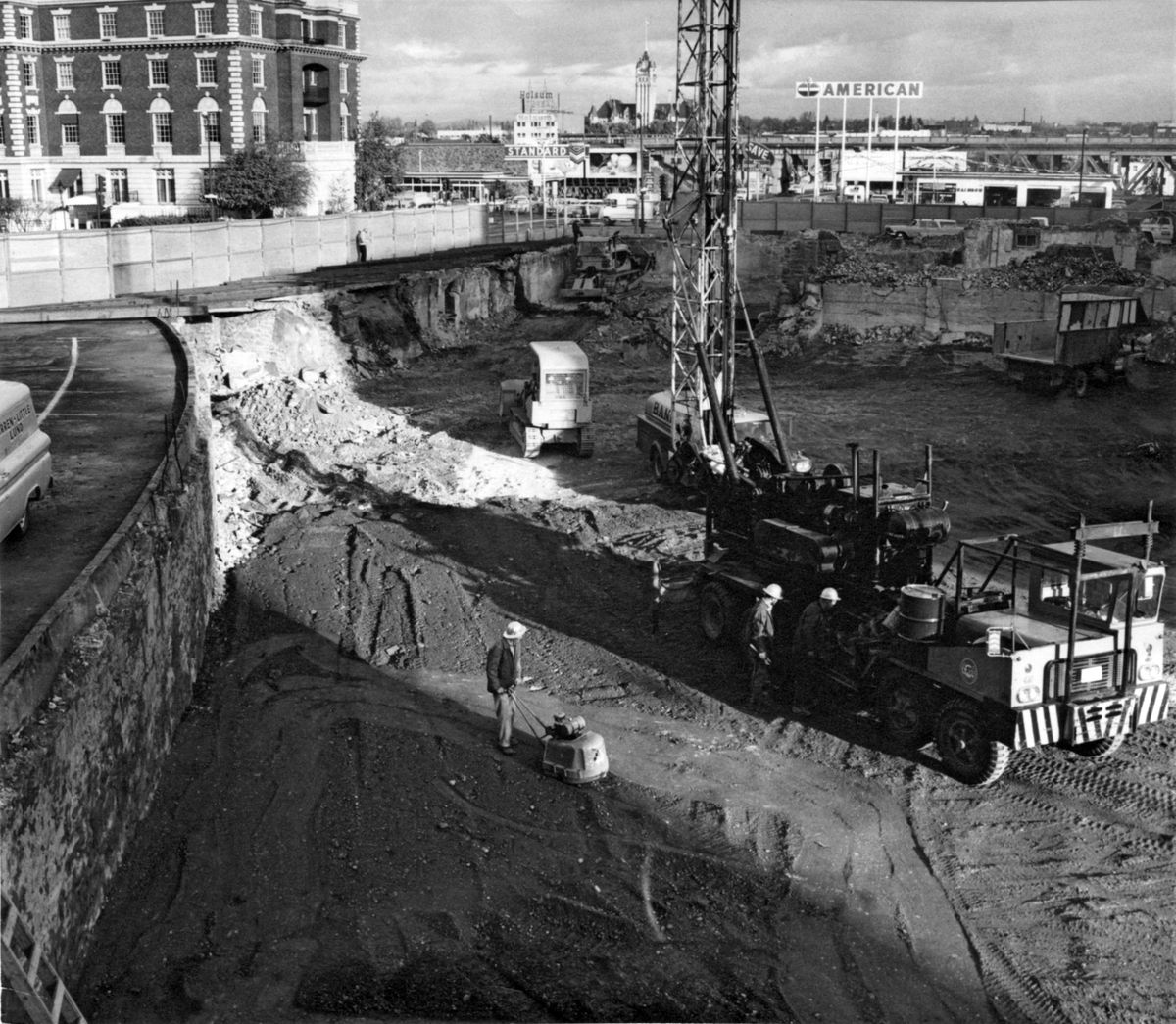

Then demolition began. Not everyone was pleased.

On Oct. 2, 1965, the Chronicle ran a story with the headline, “Demolition Job Is Creating Nostalgia for City Oldtimers.”

“Been around Spokane long enough to remember when the Spokane Amateur Athletic Club tennis courts were behind the club building on Riverside and Riverside Court? Then you’re one of those who can’t help feeling a twinge of regret as they knock down the building more recently known as the YWCA,” the article began. It described the “staged weekly amateur fight cards that jammed the gym to the rafters on alternate Fridays” at the old “S-Double A-C,” when the “youngsters wearing the red and black double triangle defended the club’s honor” against boxers from the Elks lodge, Chet McIntyre’s boys, Gonzaga University “aspirants” and competitors from the old Mekos Athletic Club in the Liberty Park district.

Facing Riverside “was a fruit stand owned by an Italian named White.” The stand was on stilts, overlooking the tennis courts 12 feet below street level. “Also on stilts and to the west against the Dodd Block was a hamburger stand that did a flourishing business on fight nights. So did Dave’s Waffle House which stood against the SAAC at Monroe and Main.”

The article ended with a quote from Wilbur Christian, described as a leading SAAC handball player, who “watched the crane swing the iron ball against the old club building. He gulped once, shook his head, commented, ‘Man, there’s a lot of history going down the drain there.’ ”

The curvy Dodd Block also received its share of stories, but primarily because of its questionable foundation and location on Riverside’s “unusual turn that architects call a serpentine curve.”

An Aug. 17, 1967, article in the Chronicle attempted to find out why the “familiar old twisty curve” was “built with such a perverse configuration.”

It suggests the contour of the land was to blame, and noted that Charles Dodd, a “farm implement dealer out of Portland,” started building his block just six days after the Great Fire of 1889. Before the fire, that area sloped down to the Spokane River. Unlike the land below the downtown Spokane Public Library and City Hall, which are underlain with trash and debris from the fire that was thrown into the small gorges, Dodd’s building was on sounder footing. But not by much.

Builders of the federal building had to go down 46.5 feet through gravel to pour footings for the new structure. Lester Cook, chief inspector for the GSA during construction, said “what’s funny is that there were two huge boulders in it, and nobody can figure out how they got there. One of the boulders was the size of a car and the other was a great big one.”

‘Built In Spite of Bureaucracy’

In September 1965, permits were issued for construction.

Heavy snowfall briefly delayed work in late December, after 1,500 cubic yards of concrete had been poured for the sub-level walls and mechanical core, but besides that work continued apace with some notable mistakes and one tragedy.

On Oct. 10, 1966, the Chronicle reported that “25,000 New Bricks Have to Be Torn Out.”

“They’re just slightly the wrong color,” Cook said. The number of bricks to be replaced were “just a drop in the bucket,” he said, noting that “there are a million pieces of masonry in the building.”

The next month, on Nov. 8, 1966, Dee Schaum, a 24-year-old apprentice steamfitter, fell to his death. He “apparently pitched headfirst about 25 feet to the concrete floor of the sub-basement, breaking his neck.”

After 18 months of work, the scaffolding was taken down, and the building was complete enough to criticize. In March 1967, The Spokesman-Review ran an article that gathered the thoughts of 12 anonymous architects and stoked a fire, saying “controversy rages even stronger over its aesthetic qualities.”

According to the article, “the building has caused much merriment. Most Spokane architects feel this levity is, of course, irresponsible at most and premature at least.” The nameless architects, however, didn’t say much and contradicted each other. The brick color was either too much of a contrast or not enough of one. The article also reported them saying the building “has its own style,” and it “is style-less.”

The Spokesman-Review’s sharp tone was mollified by its afternoon competitor in June 1967, when a Chronicle article said the building was “undeniably impressive.”

“What is perhaps most outstanding is the agreeable combining of traditional marble and dark-wood interiors with rooms of utmost modern design and convenience,” it read. “Immediately upon entering the spacious main lobby, the visitor feels the impact of generations of heavy and solid architectural influence on federal building design and construction.”

George McCue, the urban design critic for the St. Louis Post Dispatch, visited town in October 1967, and hailed the new federal courthouse, saying the “graciousness of aspect of the new Federal Building with its fine flared cornice, its craftsmanship of brick, good window modules and ornamental use of brick on an inviting podium of white stone” make it attractive.

In a note placed in a time capsule in 1967 that was unearthed in the 1980s, the architects punched back at critics. “Presently, the Federal Building is subject to severe criticism, primarily in newspaper editorials with a sports writer leading the parade,” read the note, written by John McGough. “For you with the wrecking ball, nuclear bomb, or whatever method is employed, there is an epitaph incised in the bricks under the cornice on the northwest corner which reads as follows: ‘A Monument to the Design and Construction Team - Built In Spite of Bureaucracy.’ ”

Finally, more than two years after construction began and two months behind schedule, the building was done.

“Federal Agencies Face Moving Day,” the Chronicle reported on Oct. 10, 1967.

“Last summer’s snapshots at the lake, the misplaced report the boss wanted in the spring, an extra tube of lipstick and a discarded pipe with a bite – all these are being dredged out of their hiding places in the crannies of desk drawers and coat closets as 675 federal employes get ready to pick up and go,” the article said.

Over the coming weekend, the many disparate federal agencies would be centralized. The “biggest and most unusual move” was that of the U.S. Geological Service from the Holly Mason Building on Howard Street. “An ‘accumulation of about 40 years of rocks and debris’ will have to be gathered and redistributed in the new location,” the article said.

History and future

Nowadays, the federal building is an established and aging part of the cityscape. In 2012, it underwent a $45 million renovation, and Zambon said its replacement value is around $118 million. Though the federal government used to own buildings in Colville, Sandpoint, St. Maries, Wenatchee, Coeur d’Alene and Moscow, Spokane’s building is the last monolith to remain.

U.S. District Court Judge Justin Quackenbush has been hearing cases in it for 40 years, including those for James E. Mitchell and John “Bruce” Jessen, Spokane psychologists who devised the “enhanced interrogation” techniques for the CIA, and Kevin Harpham, who placed a bomb on the route of the Martin Luther King Jr. Unity March in 2011.

“It’s been my homebase for most of my career,” Quackenbush said in a statement. “I can’t image the Spokane skyline without its unique look.”

Though its past is being celebrated, the building is still where futures are made. On Tuesday morning, a courtroom on the ninth floor held its semimonthly naturalization ceremony, where 34 people from 14 countries including Colombia, Indonesia, Iraq, Mexico, Sudan and Vietnam became American citizens.