Redemption Project unravels the past in hopes of building stronger future for inmates

With each toss of a colorful ball of yarn, the story thread unraveled.

March 17, 1991: A woman is arguing with her estranged husband. A day later, she’s dead from multiple stab wounds. He hopes their three children didn’t see anything.

Thirteen years later, the man is released from prison. He doesn’t know how to be a father to his son JR, so instead the two use meth together. JR’s sister is worried – her brother just pointed a gun at a cop.

A year later, JR is out of prison. He continues to change. He’s angry. He wants to fight someone. He hit a cop car near Portland and ran. He’s going back to jail.

It’s Oct. 28, 2008, and JR steals a bag from a woman. He’s back in jail. A year later, and still behind bars, he orders to have someone killed. He’s caught.

Three strikes, he’s out.

“This is my story,” said Joshua Phillips, a 33-year-old inmate at Airway Heights Corrections Center, as he stood in the center of the maze. “It started with my dad. It started with him, but it didn’t have to end the way it did.”

Surrounding him were a dozen inmates and a staff sponsor, all of them hanging by a thread. Literally. As they read his story aloud, they tossed the yarn until an intricate spiderweb formed.

Four years ago, Phillips would be hard-pressed to admit the mistakes he made that led to his lifelong incarceration in Washington. Let alone write them all down for a group to read aloud.

But one therapeutic program changed all of it. And he’d like the world to know about it.

“I often think of the negative impact I’ve had to my victims,” said Phillips in an email sent to The Spokesman-Review in February. “My emotions center around my remorse. I’m so sorry for hurting them.”

The program is called the Redemption Project – a 21-week-long initiative whose origins trace to Stafford Creek Corrections Center in Aberdeen, Washington, when in 2007 an inmate named Anthony “Wali” Powers developed the incarcerated-led class.

It has since moved to prisons across the state, more recently to Airway Heights in 2016, where it has found a strong following.

Staff sponsor Liz Wright, who has helped oversee classes and develop curriculum from the onset, said it has quickly become one of the prison’s most effective programs for re-entry.

Before each session even starts, she has to place at least 20 inmates on a wait list.

“As the time goes on, you see,” she said. “They get something out of it, whether they’ll admit it or not.”

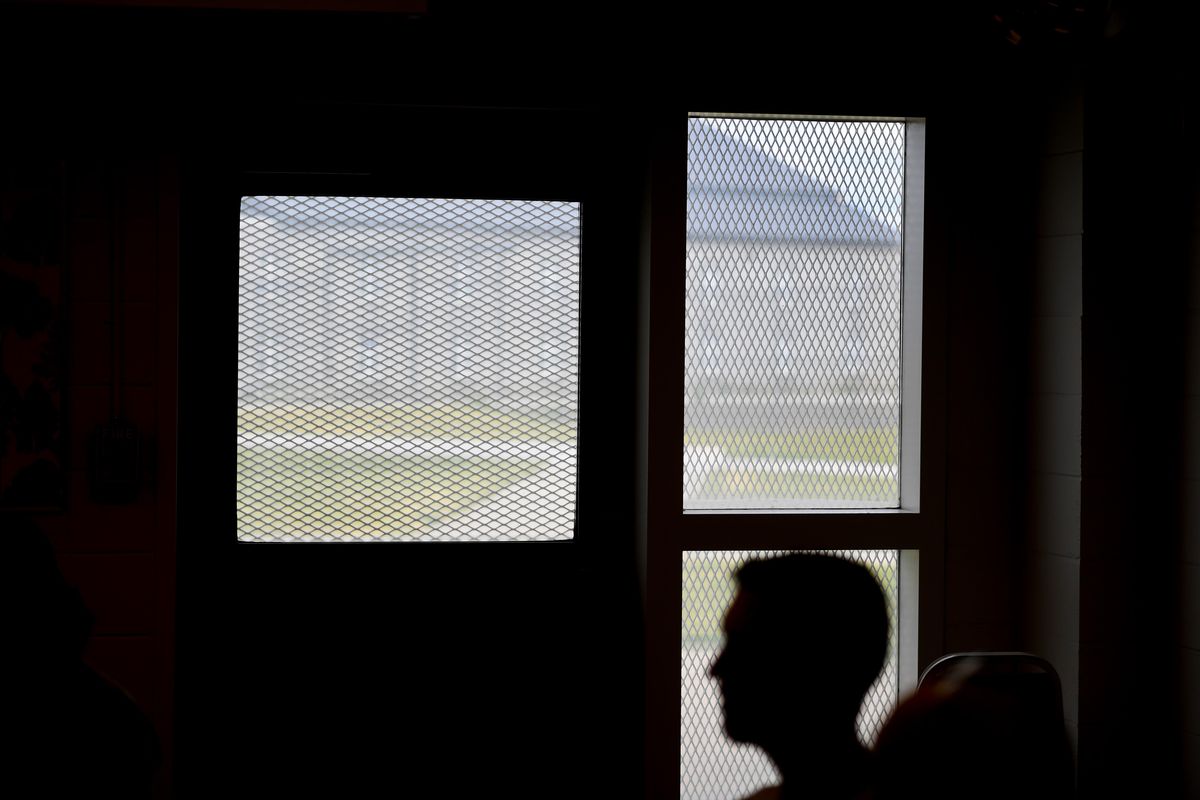

In a small room in the prison’s recreation building on Monday, a group of class facilitators gathered to develop lesson plans for an incoming group of students, with classes set to begin in late June or early July. Another group of 88 graduated Tuesday.

The facilitators – all of them inmates – are graduates themselves, and volunteer their time teaching others at morning, afternoon and two evening classes. It’s a hard job to secure, said Wright, mostly because once facilitators are in the program they don’t want to leave.

“I won’t give this up,” said 54-year-old Ricky Kerr, also serving a life sentence without parole. “I’m a three-striker, a three-time loser. If I can stop one person going down the same path, it’s worth it.”

The structure is simple: The first week is orientation and goal setting. Then the spiderweb exercise, where the students learn to open up. Kerr and Phillips said it’s one of the most difficult parts of the program, but also the most important as it sets the tone moving forward.

After that, planning for adversity, developing support networks, conflict resolution, education, job searching and so on. All the while, the inmates are filling out a booklet, wherein many of the questions have them reflecting on life before their conviction.

Phillips said it took three runs through the program before it finally clicked for him.

While research on the program is limited, prison officials said they’ve seen a clear improvement in behavior from individuals who’ve graduated.

Unlike other therapeutic classes, which are typically run by a staff member, they say Redemption is particularly adept at reaching inmates who balk at authority, since it is almost exclusively led by their peers.

“It just makes the community safer,” said Superintendent James Key. “That’s the bottom line.”

And while at least two of the facilitators are what the inmates call LWOPs – lifers without parole – Phillips and Kerr say that doesn’t stop their commitment to the program.

If anything, it might come in handy one day. A bill discussed in the Senate Law and Justice Committee last session pushed to end Washington’s life imprisonment policy by giving inmates who are well-behaved, over the age 50 and have served at least 15 years of their sentence, a chance for parole, with some exceptions for murder convictions.

Katherine Beckett, a University of Washington sociology professor who spoke on behalf of the bill in February, said that as crime rates have fallen, life sentences in Washington’s prisons have tripled.

With capacity problems looming, she said, research has shown that not only is it cheaper to not incarcerate older inmates, but recidivism rates decrease rapidly the older they get, beginning as early as the age of 30.

“It’s just something that we know to be true from so many, many studies,” she said. “This is one of the most consistent criminological findings you can discuss.”

But until the laws change, Kerr and Phillips will stay put. And perhaps continue to unspool their yarn, one line at a time.

“This program changed my life,” said Kerr, tears welling up in his eyes as Phillips placed a hand on his back. “The people in the program changed my life.”