Tim Eyman-backed initiative would upend state transportation funding

Tim Eyman’s latest anti-tax ballot measure is either a Robin Hood-like gesture for the people of Washington or a disastrous gambit that will kill the state’s necessary transportation projects.

It just depends who you ask.

On its face, Eyman’s measure is plain enough. It would limit annual motor vehicle license fees to $30 a year, eliminate a host of programs that fund local road projects and dismantle some transit agencies. In the process, it will cut $4.2 billion from transportation funding.

Eyman and other initiative backers say that will force policymakers to be more frugal and thoughtful about how they spend taxpayer money. Critics, on the other hand, say the cuts would throw into chaos an already confusing and underfunded roadwork funding mechanism, which in the most recent two-year budget is expected to generate and expend nearly $10 billion.

Eyman and his detractors do agree that if Initiative 976 succeeds at the ballot box, the way the state pays for its roads will dramatically change. Even Eyman acknowledged he didn’t have a better idea how the state should fund its roads, saying he would avoid the “temptation to play god.” Instead, the question will be forced on lawmakers if his measure passes.

And local legislators say Spokane’s most important projects would be imperiled if state lawmakers are forced to fight over what projects to save and which ones to scrap if a major slice of the funding pie is done away with by voters.

Eyman said the ballot measure – which is similar to measures approved twice by voters nearly 20 years ago, blocked by courts and, in one instance, restored by the Legislature – is driven by what he believes is overtaxation by insatiable politicians who can’t take no for an answer.

“We just hate the idea of the state government imposing really high vehicle tabs, and we hate this dishonest valuation system you guys use. We want to get rid of that,” he said, referring in part to the state’s system of car valuation. “We don’t want state government and local governments having high car tabs. We just want $30.”

The situation is far more complex, said Senate Majority Leader Andy Billig, a Spokane Democrat.

“Whatever you care about in transportation – whether it be pothole repair, the North Spokane Corridor, transit, bike infrastructure – it will likely be undermined by Initiative 976,” Billig said. “This will be such a jolt to the system that everything will be cut. Everything will be in jeopardy.”

Local impacts

Washington car owners pay a base amount of $38.75 to license their vehicles, according to the state Department of Licensing. That breaks down to a base fee of $30, a county filing fee of $3, a license service fee of 75 cents and a service fee of $5. On top of that, weight fees are added on. The average 4,000-pound vehicle is charged a $25 weight fee, which goes up as the car’s heft does, an acknowledgment that heavier cars do more damage to the roads.

In 61 Washington localities, motorists pay another car-tab tax to fund local road maintenance through what’s called a transportation benefit district. In Spokane, that adds $20 to the registration fee.

Most of this would go away if I-976 passes. The base amount would be strictly limited to $30, and weight fees and the ability for transportation benefit districts to impose fees would be eliminated.

Though the measure would have disastrous effects on Seattle’s Sound Transit, Spokane Transit Authority is still examining the issue.

“If passed, STA anticipates impacts to funding for all the services it provides including Paratransit, Fixed-Route and Vanpool, but we’re still working to fully understand specific financial implications,” according to Brandon Rapez-Betty, STA’s spokesman.

Over the next six years, the state would lose more than $1.9 billion in revenue if the measure passes, according to the state Office of Financial Management. Local governments will lose an additional $2.3 billion in the same time period.

As Billig suggested, it’s difficult to know how this would play out locally. It’s not just a simple equation involving subtraction. Instead, it would be more like taking whatever money is left over after voters cut out the $4.2 billion, throwing it into a pile and watching as state lawmakers fight over it.

What’s for sure, however, is the city’s transportation benefit district’s $20 car tab will go away. The district and fee were approved by the Spokane City Council in February 2011 to be used for the “sole purpose of acquiring, constructing, improving, providing, and funding transportation improvements” in the city, according to information from the city.

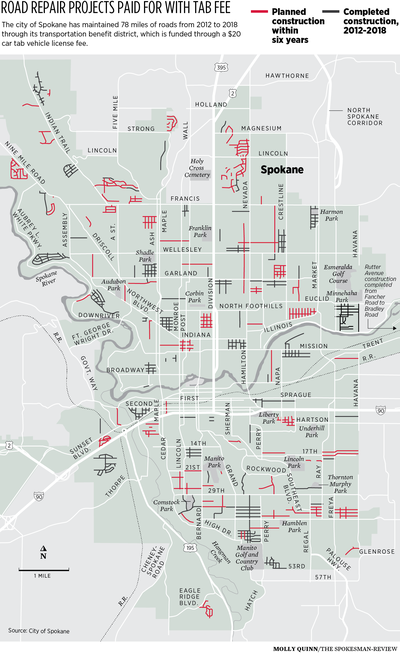

From 2012 to 2018, the city raised between $2 and $3 million a year through the program for chip seal or grind and overlay work on 78 miles of roads.

Billig and other opponents of the measure warn that the $1.5 billion North Spokane Corridor would be imperiled if the initiative passes. The north-south freeway received $879 million through the 2015 Connecting Washington Package. The $16 billion transportation spending program is funded primarily through an 11.9-cent gas tax, but $2 billion comes from vehicle weight fees, which would be reduced by Eyman’s measure.

The 2015 funding package also dedicated $2.75 billion toward debt service, illustrating how much the state has depended on credit to build and maintain its highways and how the current funding model doesn’t pay for the roadwork the state needs.

From watch salesman to crusader

Eyman began his anti-tax crusade in 1999, when he was in his 30s and selling watches in Mukilteo, Washington.

He started with I-695, which required voter approval for any state or local tax increase, repealed the motor vehicle excise tax and imposed a top license tab fee of $30 a year. Just over 56% of voters approved of the measure, but the Washington state Supreme Court deemed it invalid. The Legislature restored the motor vehicle excise tax after the court’s ruling.

In 2002, Eyman again got a measure limiting annual vehicle licensing fees to $30 on the ballot, with I-776. It passed with 51% of the vote, but was overturned by the King County Superior Court because it violated the state’s “single subject rule” by setting license fees at $30 and encouraging a new public vote on Seattle’s Sound Transit light rail program.

What Eyman was saying then is similar to what he says now.

In Eyman’s telling, I-976 has a simple message, and it shouldn’t get lost in the weeds: Voters twice approved a similar measure, politicians refused to abide by it and now they’re using the “dishonest” tax to prop up a dysfunctional and excessive system.

The goal of the measure is simple as well, he said. By forcing legislators to use a far reduced transportation revenue stream, the system will become more efficient and the money will be actually be spent on roads – not transit or bike lanes.

Anything voters hear otherwise is false.

“Politicians have nothing but threats, lies and scare tactics,” Eyman said. “No matter how much you give the government, it’s never enough.”

Spokane City Councilman Mike Fagan and his father, Jack, have worked with Eyman since 1999. Fagan, too, is a sponsor of the initiative and largely agreed with Eyman’s assessment. However, he said he parted ways with Eyman and dissolved any businesses and committees related to his initiative work with Eyman.

Fagan said his father’s old age was the main cause, but Eyman has troubles that may spell the end of his crusading career. Aside from an embarrassing episode in February when he allegedly stole a $70 chair from an Office Depot store in Lacey, Washington, he continues to fight a campaign-finance lawsuit, in which Attorney General Bob Ferguson has accused Eyman of using the initiative process to get rich, according to the Seattle Times. He has been found in contempt twice and faces a lifetime ban on directing the finances of political action committees.

Fagan, a firebrand conservative, said he’s not as critical of government as he was before sitting on the council for eight years, and that he’s open to discussing how user fees such as a gas tax or vehicle license fee could be used to fund infrastructure. But he believed any decisions about tax increases belong with the voters. That goes for fees as well.

If a city wants to create a transportation benefit district tax, the voters have to approve it, not council members, he said.

“I’m a local guy. If a local community wants a specific project, then there should be a local discussion,” he said.

But Fagan and Eyman agree the measure is a reckoning for lawmakers.

“People are angry,” Fagan said.

Eyman said we are living in a “tapped-out moment with people” and warned that “voter surliness is coming about.”

Both said they weren’t alone in their concerns, and pointed to the 350,000 signatures they gathered to get the measure on the ballot. The committees Eyman oversees spent $670,000 to gather those, equating to about $1.90 per signature.

Business, labor, environmental groups oppose

Billig had his own warnings.

Transportation is “the foundation for our economy,” he said, and gutting the state’s transportation funding system would have immeasurable repercussions.

He described the measure’s impact as delivering “such a blow to our transportation infrastructure,” but he said that he couldn’t precisely say how the measure would affect the state’s projects due to its potential to create chaos.

“We don’t know,” he said. “We can’t tell you. But it will have dramatic effects.”

Stripping $700 million out of state and local transportation budgets each year for the next six years would clearly damage some projects. Billig and state Rep. Marcus Riccelli, a Spokane Democrat who sits on the House transportation committee, said the loss of money would simply start a “money grab” by lawmakers to fund whatever project is imperiled in their district.

“We’ll have to go back, and the Legislature and the DOT will have to go and figure out what projects are going to get delayed, which ones will get scrapped,” Billig said.

Riccelli was less measured and described a situation in which legislators from every corner of the state begin fighting over the funding revenues that remain in place – namely, gas tax revenue.

“We worked so hard as a region to garner funding. I think we’re positioned well right now, but there are a lot of transportation projects across the state and plenty of my colleagues …” he trailed off, not finishing his sentence. “This is about protecting our fair share.”

The two lawmakers are not alone in their worries. A slate of business, labor and environmental groups has joined numerous elected officials in opposition.

The Association of General Contractors of Washington and Greater Spokane Inc. are against it, along with the Sierra Club and Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy. So are the Washington State Patrol Troopers Association and El Centro de la Raza. Numerous labor unions and business associations have joined to fight the measure, including Washington State Labor Council AFL-CIO, the Washington and Northern Idaho District Council of Laborers, and the Association of Washington Business.

About 40 mayors, senators, representatives and city council members are named a “coalition” on the “No on Tim Eyman’s 976” website. At a recent event marking progress on the North Spokane Corridor, Democrats and Republicans alike praised the bipartisanship that fully funded the freeway, and warned against measures that threatened it, without naming 976.

Keep Washington Rolling, a political action committee against the measure, has raised $1.8 million. Microsoft gave $400,000. Vulcan Inc., the philanthropic organization created by Microsoft founder Paul Allen, gave $200,000, and the state chapter of the American Council of Engineering Companies and Expedia each gave $100,000.

Locally, Avista gave $25,000, the Inland Northwest Associated General Contractors gave $20,000 and the Cowles Co. gave $15,000. The Spokesman-Review is owned by a subsidiary of the Cowles Co.

Riccelli said it was a shared concern about safety and degraded infrastructure that bound the opposition together.

“This measure would cut critical transportation funding. We need good roads and transit options. People need to be able to get to work. We depend on a transportation system that’s in order,” Riccelli said, describing why so many organizations oppose the measure. “It’s a bad deal. I think Eyman spends too much time sitting in his chair, coming up with bad ideas.”

The north-south freeway

Probably the biggest Spokane region project that could be affected by Eyman’s measure is the North Spokane Corridor, otherwise known as the north-south freeway.

The measure itself wouldn’t cut to the heart of the project, which is largely funded through the gas tax-supported Connecting Washington package passed by the Legislature in 2015.

Instead, it could be put in jeopardy if the complex system the state has set up to pay for transportation infrastructure – which includes registration fees – is thrown into disarray by the measure.

“It’s really misleading to say that the North Spokane Corridor is fully funded without explaining that it’s all based on revenue projections that will be reduced if I-976 passes,” Billig said. “It’s not fully funded like the money’s in the bank. It’s based on revenue projections.”

Riccelli said before Democrats and Republicans committed the final $879 million piece of the freeway’s funding puzzle, the Spokane region was getting back 80 cents for every dollar it contributed to state transportation funding. With the freeway funding, Spokane is “subsidized when it comes to transportation” and gets $1.30 for every dollar it contributes.

“We worked really hard in a bipartisan way,” he said. “Now that’s at risk.”

That’s the point, Fagan and Eyman said, both asserting that the Legislature should tap the state’s surplus of $3.5 billion to pay for the lost revenue if the measure passes.

Fagan would not say whether he was concerned about delaying the North Spokane Corridor, which will run through the City Council district he represents. Instead, he said that if the freeway is truly at risk, it means legislators lied to voters when they said it was funded by gas taxes.

“At the end of the day, if they’re going to hold the North Spokane Corridor hostage, did they lie to the voters again about the gas tax?” Fagan said. “At the end of the day, folks, you need to remember that Sen. Michael Baumgartner led the charge for the gas tax to get the North Spokane Corridor done.”

Baumgartner, a Republican, is now the Spokane County treasurer.

Instead of issuing dire warnings, Fagan said state and local decision makers should be “planning for impact, planning for reallocation, planning to readjust their belts.”

“These guys started the last legislative session sitting on $3.5 billion,” Fagan said. “I would say sit down and shut up. You’re sitting on more money than you’ve ever had and you’re whining about a $30 license tab?”

Eyman had a similar take, and suggested state lawmakers should be forced to find a way to pay for the freeway.

“Use the surplus,” Eyman said. “Justify funding and get rid of non-road stuff. Move money around. Use existing revenue more effectively.”

After the measure passes, Eyman said, legislators will cycle through the “five stages of grief” and they’ll fix the system.

“Denial, anger, depression, acceptance. I forget what the fifth one is, but once they reach it they’ll say, ‘Well the voters have spoken. We better do something,’ ” Eyman said from his phone while driving on Interstate 5. “Will they be satisfied? No. They seem to have an insatiable tax appetite.”

Editor’s note: This article was changed on Oct. 7, 2019 to reflect how Initiative 976 would effect transportation benefit districts, the impact of initiatives 695 and 776, and the amount Eyman raised to collect signatures for the most recent measure.