A half-century of hope: Created 50 years ago, iconic POW/MIA bracelets linked people at home to missing soldiers

An iconic piece of jewelry turns 50 this year – a simple metal bracelet that is like a miniature time capsule from the Vietnam War.

A California student group called Voices in Vital America first created its popular POW/MIA bracelets in 1970. After meeting the wives of missing pilots, organizers wanted to raise awareness about the conflict’s prisoners of war and missing in action.

From 1970 to 1976, the group distributed about 5 million bracelets initially costing $2.50 to $3, with proceeds to pay for awareness bumper stickers and ads. Each band was engraved with a rank, name and date the person went missing.

People vowed to wear them until that person came home or remains were found. But, eventually, most of the bracelets came off. Some were sent with notes to service members who did return. They were mailed to family or more often left at graves and memorials. Many were stored and forgotten.

“I wore this bracelet all through middle school,” said Sheila Geraghty, 59, executive director of the Historic Flight Foundation at Felts Field. “I’m surprised I still have it. Mine is very worn.”

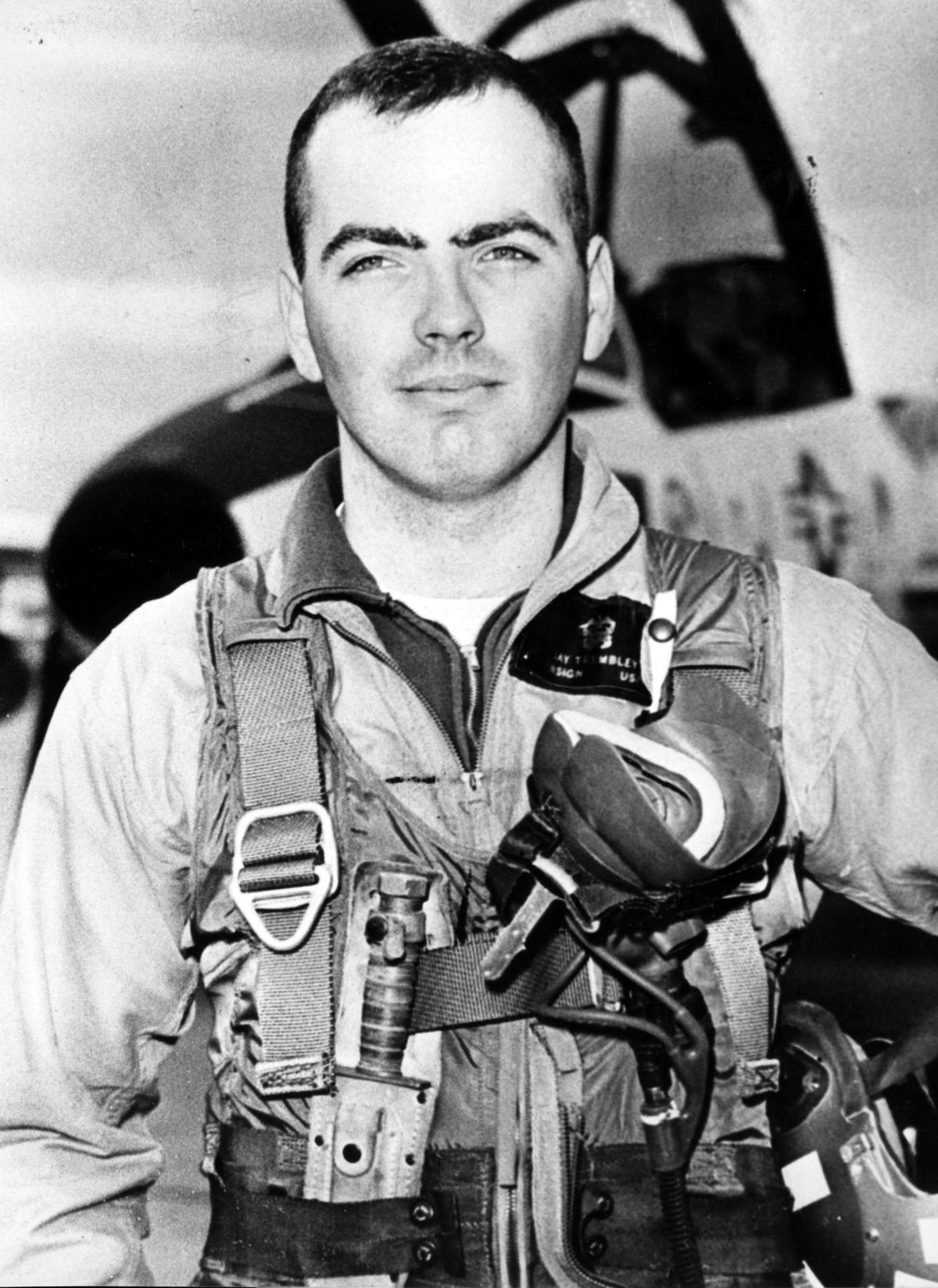

Geraghty wore the bracelet for her father’s first cousin, Lt. J. Forrest Trembley, a Navy pilot whose plane was shot down Aug. 21, 1967. He was born and raised in Spokane.

Reports say Trembley and a crewman took off in their A-6A Intruder from the USS Constellation on a strike mission against the Duc Noi rail yards near Hanoi. Upon leaving the target area, their aircraft and another one in the flight were attacked by enemy MiGs.

When last seen, the two aircraft were disappearing into the clouds near the Vietnamese-Chinese border. The last radio message from Trembley indicated the MiGs were in hot pursuit.

Geraghty said relatives when she was young had known his plane went down, but they still held out hope for some time.

“I would have been about 9 years old when the bracelets first came out,” she said. “I know our family got a whole bunch of these bracelets, and everyone wore one.”

The U.S. listed 2,646 Americans as unaccounted from the Vietnam War in 1973. Today, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency says that number is now at 1,587 U.S. military and civilian personnel. More than 58,200 Americans died during the war or remain missing.

Lt. J. Forrest Trembley 8-21-67

“I remember it was a really sad time for our family,” Geraghty said. “Me and my sisters were very close to his mother who is our Aunt Anna, my grandpa’s sister. I remember when we were little, we used to go to our Aunt Anna’s house all the time. She’d bake us cookies and make us lunch.

“I remember she frequently cried thinking of Jay.”

Trembley had one sister. He also was married and had a son. “He looks a lot like his dad, very handsome,” Geraghty said.

In 1993, news finally reached the family, a Seattle Times article said. Documents and photos confirmed Trembley’s death. Much later, his remains were identified through DNA analysis. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery on April 1, 2005, nearly 38 years after his disappearance.

Geraghty knows she wore her bracelet consistently during seventh and eighth grades in Spokane.

“I wore it a lot in honor of my Aunt Anna,” Geraghty said. “I think after middle school, I wore it off and on. It’s not very fashionable, but it was always here. I remember wearing it as often as I could, but I probably stopped wearing it in high school.

“I think we were pretty sure he had been shot down and was missing in action. I think it was nice to wear the bracelet when you were remembering and hoping that maybe he wasn’t missing in action, hoping he was a POW.”

She also said it meant a lot to the family all those years later to have his remains identified.

“The whole thing was you were supposed to wear the bracelet until the person was found. After a few years, either you give up or forget about the bracelet. I think the family was really surprised that one day we were contacted.”

Capt. Melvin Ladewig 8-24-68

Spokane resident Steve Peck, 64, remembers the popularity of the 1970s-era POW/MIA bracelets worn by many of his classmates.

“The first I saw them was in 1972 while a high school freshman in Colorado Springs,” Peck said. It was nearly 15 years later when he decided to wear one while in the Air Force.

In the 1980s, rumors still lingered about the missing in Vietnam. Peck’s stainless steel bracelet was made by a different organization long after VIVA closed in 1976. Yet the one he received for Capt. Melvin Ladewig is similar with rank, name and date of loss – along with an etched USAF.

Peck chose the bracelet for Colorado and to honor the Air Force and his father’s World War II service. Ladewig, a pilot systems operator, had joined the Air Force from Colorado and served with the 497th Tactical Fighter Squadron.

Presumed killed in action, Ladewig went missing Aug. 24, 1968. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency lists his status as unaccounted, as remains were never recovered. Ladewig was in a F-4 Phantom II, call name “Agile 2,” for a night reconnaissance mission over North Vietnam.

After the lead aircraft dropped flares on the target, Agile 2 made a bomb run. Seconds later, the lead aircraft’s crew saw a fireball northwest of the target and couldn’t make radio contact with Agile 2. Search and rescue teams were unable to locate a crash site or missing crew members.

Peck worked with pilots who had flown Vietnam War missions and knew some of those missing in action. He also was inspired by a speaker.

“It was through Project Warrior,” Peck said. “We had a speaker who was a POW in the Hanoi Hilton for five years. He made it clear there was still a lot of servicemen unaccounted for.”

That’s when he got the POW/MIA bracelet and wore it for at least 10 years. Today, Peck said he still wears the bracelet at veteran activities or special events.

“I think it’s important. I tried to explain that to a younger veteran from the second Gulf War. He told me, ‘We have those, but we call them KIA bracelets now’ because they don’t have anyone missing for those more recent conflicts.”

He’ll keep his POW/MIA bracelet for now.

“I keep checking in, and even though there has been a lot of progress in repatriating remains, he’s still missing. I look forward to and hope for the day that the Ladewig family gets their missing son and brother home. Then I can finally retire my bracelet and try to get it back to the family.”

S/Sgt. Perry Kitchens 11-3-70

This reporter’s bracelet came from a drawer. It was my mother’s. Occasionally, I’ve looked at the name and wondered. I wish I’d asked her why she got the bracelet.

There are vague childhood memories of people wearing the POW/MIA bracelets. Thanks to the Vietnam Memorial’s online digital images, I recently saw the face of Army Sgt. Perry Kitchens for the first time. From Decatur, Georgia, he was only 21 when he died in 1970.

I’ve also learned what’s believed to have happened to him. He was in the 5th Transportation Command with duties that included support of amphibious operations and supplying ammunition primarily by heavy boat.

On the afternoon of Nov. 2, 1970, Kitchens and other crew members departed Da Nang on a resupply mission. The next morning, Nov. 3, helicopter pilots sighted the capsized craft.

There was no apparent hostile action. At the time, only one crew member’s remains were found. By December, divers gained access to all compartments of the craft, but no survivors or evidence of remains were found – only pieces of clothing, small arms ammo cans and a radio.

Seven years later, on March 16, 1977, “The body of Perry Kitchens was returned to U.S. control and subsequently positively identified,” said the POW Network. “There has been no word of the rest of the crew.”

Vietnam-era bracelets still are around and sometimes are left at memorials, said Nicole Frazer with the Spokane-based Washington State Fallen Heroes Project.

“A lot of people leave them at the traveling wall and the Vietnam Memorial,” Frazer said. The national site eventually archives them. Now, newer generations of bracelets for the fallen are worn.

“It’s moved to KIA because there are not many POWs or MIAs in the current two wars, which would be Iraq and Afghanistan,” she said.

“I’d say Memorial Day is not a day to thank a veteran. It’s a day to remember those who lost their lives protecting our freedoms. And the bracelets are a great remembrance of those lives.”

The bracelet naming Perry Kitchens now sits on my desk at home this Memorial Day. If I ever visit the Vietnam Memorial, I’ll look for his name and remember.