In 1991 more than one-third of Washington was represented in the Legislature by two parties. In 2021? Hardly any.

Washington’s polarized political landscape has long been seen in the results of statewide elections, with counties around Puget Sound reliably Democratic blue and those east of the Cascades solidly Republican red in votes for president, governor or the U.S. Senate.

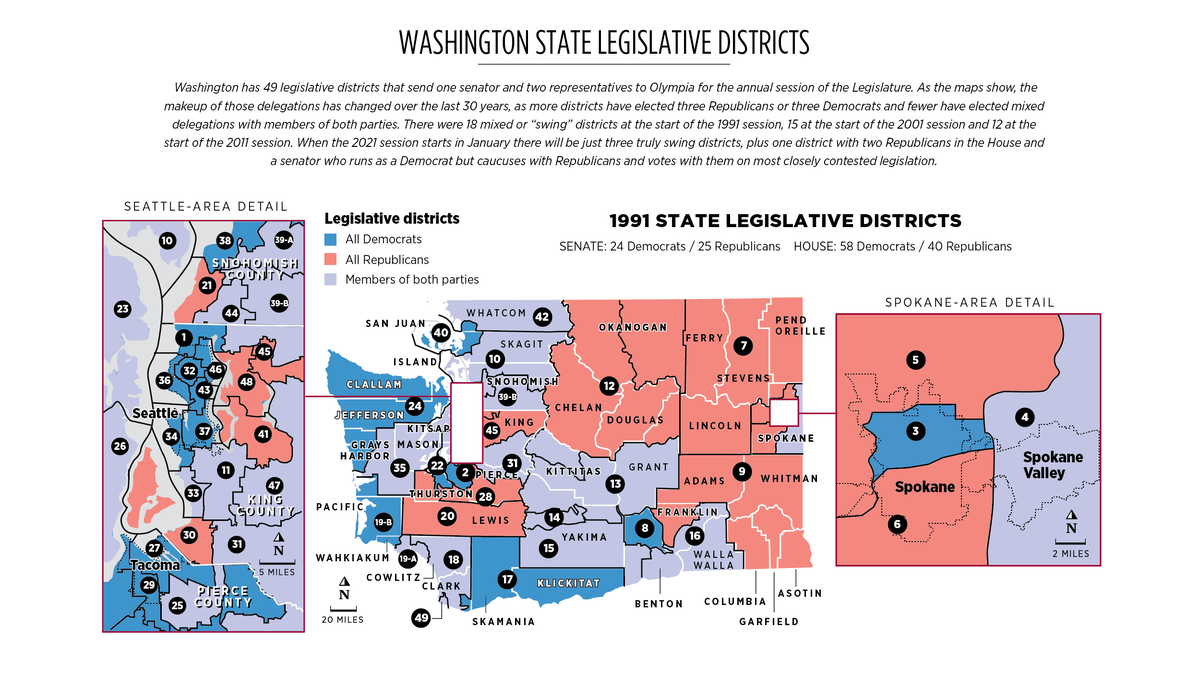

For many years the Legislature was a place where bipartisanship was easier to map. Some legislative districts had three Democrats, some had three Republicans, but a significant number – more than a third of the districts in 1991 – had at least one member of each party in their three-person (two representatives, one senator) delegation.

The numbers of those bipartisan or “swing” districts dropped slowly for three decades until this year, when only three of the 49 districts – two between Everett and the Canadian border, and one that straddles the Puget Sound – have true bipartisan representation. Another district on the Olympic Peninsula has two Republicans in the House and a nominal Democrat in the Senate, but Sen. Tim Sheldon of Potlach caucuses with Republicans and usually votes with them on closely contested legislation.

East of the Cascades, all legislative districts have three Republicans except one: The 3rd District which covers much of the city of Spokane, has three Democrats. Republican districts are also the rule in rural parts of Western Washington, while districts in the heavily populated, urban Interstate 5 core are solidly Democratic.

It is an example, some political observers say, of the type of partisan “sorting” happening around the country.

“The urban-rural sorting has been taking place for years,” said Cornell Clayton, director of the Thomas S. Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University. Democrats have increasingly become the party of urban cosmopolitan voters and Republicans a rural nationalist party.

“In the suburbs, that’s where the battles have been waged,” he said.

This could be seen nationally in the presidential race between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, said Matthew Levendusky, a political science professor who holds an endowed chair for Institutions of Democracy at the Annenberg Public Policy Center at the University of Pennsylvania.

“Two big things happened to put Biden over the top this time,” Levendusky said in an email. “First, he ran up big margins in the cities and especially their dense suburbs, and he did slightly less bad in rural areas.”

That urban-rural divide is tied to the polarization among white voters by levels of their education, he said. Whites with college degrees have shifted from Republican to Democrat over the last few cycles, but those without a college degree have continued their shift in a Republican direction.

A good example of that shift could be seen this year in southwest Washington’s 19th District, which includes timber, farming and fishing communities along the mouth of the Columbia River and the Pacific Ocean. From 1989 to 2017, the district sent three Democrats to Olympia, who were sometimes re-elected with no GOP opposition. It voted for Democratic presidential candidates, sometimes by significant margins, until 2016.

Four years ago, the two counties in the district, Grays Harbor and Pacific, voted for Trump, and it broke the legislative trend by electing Republican Jim Walsh to the House. This year, the counties also supported Trump and replaced Democratic Sen. Dean Takko, who has a combined 15 years between the House and Senate, and 20-year Rep. Brian Blake with Republican challengers.

“It’s hard for a Democrat to be successful in a rural areas,” said Todd Donovan, a political science professor at Western Washington University who researches state and local elections and representation. “The New Deal Democratic brand is gone.”

The second factor that may be reflected in the shift in Washington’s legislative delegations is the nationalization of state and local politics, Levendusky said. Those local races used to be about local concerns. Now they tend to be a referendum on national factors.

“Everything down the ballot is so nationalized,” Donovan agreed. “People are voting straight tickets, seeing things through partisan lenses.”

That makes it less likely voters will split their state House votes between a Democrat and a Republican, or vote for a Republican for the state Senate and Democrats for the House.

This year, that might have helped equal out the gain Senate Republicans had in the more rural 19th District with a Democratic pickup in an urban-suburban district in the Puget Sound area. Republican Sen. Steve O’Ban lost to Democratic challenger T’wina Nobles in the 28th District, which includes parts of Tacoma as well as Lakewood and areas around Joint Base Lewis McChord.

The partisan divisions in both chambers will be the same next year as they are now, although the number of bipartisan districts dropped from four to two.

One of the biggest shifts over the last 30 years has been in the 5th Legislative District. In 1991, the 5th covered northwest portions of Spokane city and county. It sent three Spokane Republicans to the Legislature that year although at the time it was considered Spokane’s swing district, having elected members of both parties in the previous decade. The 3rd was reliably Democrat and the 6th, 7th and 9th reliably Republican.

The 4th, which was and remains centered around the Spokane Valley, had started a brief, four-year flirtation with being bipartisan by electing Democrat George Orr along with Republicans Mike Padden and Bob McCaslin. With the 1994 election, however, the district went back to being among the most reliably Republican in the state.

After the 1990 Census, faster population growth in Western Washington meant Eastern Washington had to lose a district. The newly formed redistricting commission, whose members are appointed by the top party leaders in the House and Senate, moved the 5th out of Spokane.

It landed in suburban King County, in the suburbs east of Bellevue, and was bipartisan for a few years. By 1996, however, its delegation consisted of three Republicans, including Sen. Dino Rossi who in 2004 and 2008 would be the GOP candidate for governor. It stayed solidly Republican until 2012, when Democrat Mark Mullet won the Senate seat but the House delegation stayed Republican until the 2018 election.

This year it was solidly Democratic enough that Mullet faced Ingrid Anderson, a progressive Democrat backed by Gov. Jay Inslee, in the general. Mullet is ahead by 69 votes. A recount changing the race in Anderson’s favor won’t alter the Senate’s partisan split but would replace a moderate with a progressive in the Democrats’ majority caucus.

The shift in the 5th may be a sign of the influx of people into some suburban and exurban districts, Donovan said. “The population’s just been exploding in some areas.”

Population growth may also mean the districts are becoming more homogenous, he added.

“People are attributing it to Trump … but it clearly started before him,” Donovan said.

Clayton agreed that the shift isn’t tied solely to Trump and his impact on the political landscape: “Trump is a symptom as much as a cause.”

It may be more a sign that the old adage that “all politics is local” does not currently hold sway and local races are tied to national politics.

In the last 30 years, the largest shifts in legislative control have been tied to national political shifts. Democrats had a near two-thirds majority of 65-33 in the House in 1994 before the Republican wave tied to Newt Gingrich’s Contract with American flipped that to a 62-36 advantage for the GOP.

After the 2000 election, which was so close the presidential election was decided by a U.S. Supreme Court ruling over ballots in Florida, the Washington Legislature was also closely split, with a 49-49 tie in the House and a 25-24 majority for Democrats in the Senate.

The Senate was again 25-24 Democrats and the House 50-48 Democrats after the 2016 election, but Democrats may have ridden an anti-Trump blue wave in 2018 to get a nine-seat majority in the Senate and 16 seats in the House.

National races tend to revolve more around cultural issues – religion, abortion, gay rights or the 2nd Amendment – than economic issues, government spending, infrastructure or health care, Clayton said. When cultural issues hold sway, they speak to a person’s identity, are hard to compromise on and can expand to cover a wide variety of topics.

“The pandemic has become a cultural issue. Wearing a mask is a cultural issue,” Clayton said.

As long as the parties are aligned with issues that speak to a voter’s cultural identity, it’s probably less likely that they will “split their ticket” between Democratic and Republican candidates, he said.

One other factor that can work against bipartisan representation in a legislative district is the way the boundaries are drawn every decade after the U.S. Census data is released.

The maps that accompany this story look backwards in 10-year increments from this year’s election. They show the makeup of Legislatures in the final statewide general election before the boundaries were redrawn.

As a result of partisan fights and court battles over redistricting for much of the 20th century, Washington voters approved a bipartisan commission to rearrange its boundaries every four years as a way to avoid gerrymandering – the practice of gaining partisan advantage through oddly shaped districts.

The Senate majority and minority leader along with the House speaker and House minority leader each appoint one member to that commission. The boundaries they draw must be approved by at least three of the four members. The Legislature must then approve the maps with only minimal changes allowed.

That doesn’t mean some compromises aren’t made in favor of one party’s incumbents as the process takes place over a year of hearings or study. But it can solidify a party’s hold on a particular district with calculated movements of key precincts.

In 2011, for example, Spokane’s 3rd District was made more Democratic, and its 6th District more Republican when Spokane’s legislative boundaries were redrawn.

The two had been solidly Democratic and Republican, respectively, for more than a half century, but in 2006 and 2008, at least one Democrat had captured a legislative seat in the 6th. It was being called a “swing” district by some political observers, although the election results probably were tied to the strength of the candidates as well as partisan shifts in the residents.

But Spokane’s districts had to expand to include more residents because the state’s overall population was larger, the growth was faster in Western Washington and the number of legislative districts wasn’t changing. In the redrawing, precincts that usually vote Democratic in national and statewide elections were added to the 3rd, while those that usually vote Republican were added to the 6th. Since that time, Democratic candidates have come close but not won a legislative seat in the 6th.

House Minority Leader JT Wilcox, R-Yelm, said he thinks the shift away from bipartisan districts in the Legislature may be partially a result of political “sorting,” or people not wanting to live around or associate with people who don’t agree with them politically.

It may also have something to do with redistricting, Wilcox said, but if that’s the case as a member of the minority party, he would want the House Republican appointee to the redistricting commission to push for more swing districts and fewer districts where Republican collect more than 60% of the vote.

“We’d want a chance to win as many swing districts as possible, and there’s a higher chance of that in a good year,” Wilcox said.

House Majority Leader Pat Sullivan, of Covington, said Democrats haven’t talked about their plans for redistricting yet, other than to push for a “broad spectrum of voices” to be heard in the redrawing of lines.

“Since the last redistricting, things have changed so much,” Sullivan said. He was surprised at how quickly some districts, like the 5th District in suburban King County shifted, but doesn’t think it can be tied to deliberate strategies in redistricting.

After all, he said, those lines were drawn in 2012 and “I don’t think you could plan that out” eight years into the future.

Editor’s note: An early version of this story failed to note that the 26th District that covers parts of Pierce and Kitsap counties has a bipartisan delegation.