‘The most popular Cougar.’ Bob Robertson, who presided over Washington State broadcasts for 52 years, has died at 91

Brian Jeffries estimates he was 13 years old, maybe 14, when he and a childhood friend from Tacoma began gazing into the future, mapping out what they wanted to do and who they wanted to be when they grew up.

Dreaming, fantasizing, imagining, as young kids do.

A sports fanatic and radio nut who’d grown to idolize the man – and voice – behind the broadcasts of the local minor league baseball team, the Tacoma Rainiers, Jeffries had it on the tip of his tongue.

“I told my friend, ‘Gosh I’d love to be a sports announcer like Bob Robertson,’ ” he recalled.

The friend responded, “Well, he’s my next-door neighbor.”

“You’re kidding me,” Jeffries answered.

So, for weeks, Jeffries pedaled a bicycle to his friend’s house, always crossing his fingers Robertson would return home at the same time he arrived. Of course, knocking on the front door was too daunting of a proposition for the young boy, given his admiration. But one day, Robertson’s car and Jeffries’ bike pulled in at the same time, and the opportunity finally lined up.

“From there on, I was just infatuated and he kind of mentored me at that point, encouraged me,” said Jeffries, who enters year No. 34 as the radio voice of University of Arizona football, baseball and basketball. “He used to recreate baseball games, the Triple-A team there in Tacoma and he invited me down to the studio one time to watch how he did it. I was a young kid, I was just amazed watching it and he was kind of my young idol and I made up my mind that’s exactly what I wanted to do.

“He just always encouraged me.”

Robertson, who spent more than half of his life presiding over Washington State football broadcasts, died Sunday at his home in University Place. He was 91 and surrounded by family at the time of his death, according to a school press release.

A specific cause of death is unknown and date hasn’t been set for Robertson’s memorial service, but The Spokesman-Review learned his family intends to wait until the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic ends.

For legions of WSU fans, Robertson’s name, perhaps more than that of any coach, player, broadcaster or writer, is the one that comes to mind when considering the last half-century of Cougar football. His notorious tagline, “Always be a good sport, be a good sport all ways,” may be as synonymous with WSU football as the “Go Cougs” slogan itself.

Robertson’s association with the school began in 1964 and culminated 52 years later, in October 2018, when he announced his immediate retirement prior to No. 25 WSU’s upset of No. 12 Oregon in a showdown that was featured on ESPN College GameDay.

“He’s the most popular Cougar in the state of Washington,” former WSU coach Mike Price said Monday over the phone. “… I just loved him to death and he was just as great off the field as he was on the air. … He was the most popular person, the most popular Cougar, that I’ve ever known.”

Over the years, one of Price’s favorite hobbies has been rummaging through boxes that contain cassette tapes of historic WSU football games, and memorable Robertson calls. It’s a way for Price to relive the most successful stint of his career and replay broadcasts he was never able to hear as a coach.

“I do a lot of fishing up here in Coeur d’Alene on my boat and I’ve got my stereo and I’ve got a bunch of old cassette tapes that I listen to some of the old games he did,” Price said. “Just for the voice and the expressions and everything.”

From his own home in Coeur d’Alene, another ex-WSU coach, Jim Walden, spent time Monday reflecting on his relationship with Robertson – something that manifested from a piece of advice given to him by a former coach, Wyoming’s Bob Devaney.

“(Devaney) told me, in uncertain terms, ‘One of the most important people you’ll ever have on your side is your radio play-by-play person,’ ” Walden said. “He said, ‘Because, it doesn’t matter how many people come to the games. You may get 50,000 people in the stands, and they’re not listening to the radio, but you can have a million people over a three-hour broadcast that he can have some influence over the job you’re doing.’

“So, when I got my first job here at Washington State,” Walden said, “I made sure Jim Walden and Bob Robertson were always going to be good friends.”

Mississippi State’s Mike Leach, at the helm of the WSU football program for the last seven years of Robertson’s famed career, said Monday in a text message, “Bob Rob was maybe the most prolific broadcaster for any school, the most respected, and the most loved. He has had a huge impact on WSU. I cherish the fact that I had the honor to know him.”

For more than five decades, Robertson’s voice and WSU football games were one in the same. For the vast majority of those years, he was in a play-by-play role – Robertson only moving to the analyst seat for the final eight years of his career. From 1964-2016, he called 589 consecutive games. There was one absence, however, at the 1981 Holiday Bowl, but only because local radio was not permitted to broadcast. Robertson also called Cougar basketball games for two decades.

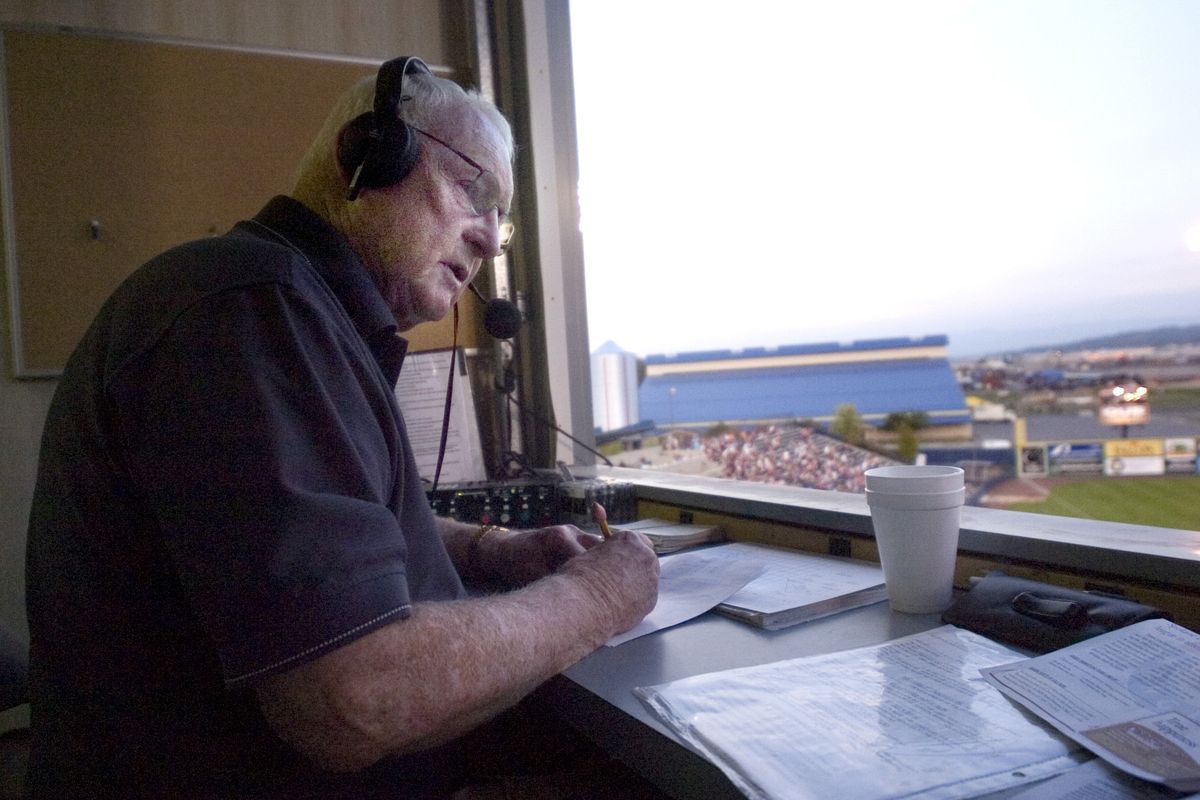

In the mid-1990s, Jerry Kyllo began working on WSU’s football broadcasts as an engineer/producer. In some ways, you can think of him as Robertson’s offensive coordinator – “basically you’re running the show,” Kyllo explained. Among other things, Kyllo set up the clunky equipment, communicated commercial breaks and timeouts to his play-by-play announcer and flipped through a book of verbal cues, shoving different reads into Robertson’s face at various stages of the game.

The first time Kyllo shared the booth with Robertson came in the 1994 season opener against Illinois at Chicago’s Soldier Field – a narrow 10-9 WSU win. His favorite Robertson tale, though, came two years later, when the Cougars traveled to Philadelphia to play Temple. The broadcast booth, Kyllo describes, “was basically a 4x8 sheet of plywood hung from the roof of old Soldier Field.”

Not much space to broadcast a college football game, let alone stand.

Robertson was mid-broadcast when a member of the station’s sales team walked into the booth, unaware of the beam hanging from the roof, and met a cruel reality.

“Walked into that thing and laid him out flat,” Kyllo said. “Bob looked down and just kept on announcing. We’re all trying to revive him and he’s got a big old knot on his head.”

Robertson’s life took a tragic turn when Joanne, his wife of 59 years, died in 2011 – the same year Robertson traded his play-by-role to become an analyst.

“She was a really kind lady,” Kyllo said, “and our daughter just fell in love with Joanne.”

Up until Robertson gave up his headset for good, he was a pseudo celebrity in the press box, drawing visits from opposing announcers, team officials and writers who all made it a priority to pop in and greet the broadcasting giant before kickoff.

“He was one of these guys you’d probably put up on a pedestal,” Kyllo said, “but once I got to know him, he was just another friendly person. … He loved the Cougs, he loved being with people, he loved talking to them and greeting people. He would’ve been the best greeter of Walmart of anybody.”

It was the familiarity of Robertson’s voice on a WSU football broadcast that made him such a revered figure among Cougars fans, but those who shared his line of work could also identify the subtle traits that made him a unique talent.

“There are objective fundamentals to doing this. There are things that are required,” said Matt Chazanow, the Voice of the Cougars since 2015. “There are pieces of data that are nonnegotiable, and then there are ways to present those things. So for instance, there’s down and distance, time and score. If you’re doing 70 on the highway, the simple fact that, can you understand what the hell is going on? Because you can’t see it.

“So, one of the things Bob did that’s so hard, that’s so elite, is he did something called being on the play. And that is to say, his timing was just amazing. He was always on the play. He told me, we would talk about how he did it and he attacked it. What that means is, when you do that appropriately, when you do that right, the crowd rises underneath you at a point in time that makes a listener – whether they realize it or not, it brings them into it.”

Robertson was deep into the home stretch of his career, a WSU and College Football Hall of Famer, a 12-time Washington Broadcaster of the Year and in just about every respect, a living legend, when Chazanow arrived in Pullman five years ago. So, the 30-year-old play-by-play announcer was admittedly thrown for a loop when Robertson arrived in the booth and asked Chazanow where he preferred to sit. This, mind you, in a booth that’s held Robertson’s namesake since 2009.

“I was like, ‘Bob, it’s literally your booth. I’ll sit on the roof if you want me to ,’ ” Chazanow said. “I’m forever calling games in the Bob Robertson Suite. Like, ‘You tell me where you want to sit. How about that?’ But he loved it. He always talked about his wife, too. I always knew I was living in special moments when I was starting this off, by doing it alongside him and in some ways with his legacy in mind.”

In 1999, the Tacoma Rainiers chose to separate with Robertson after 14 years. Seeking another opportunity in minor league baseball, he dialed up the Spokane Indians and managing partner Bobby Brett. Robertson wasn’t pushy, but if they had an opening, he’d certainly be grateful. The broadcaster had hardly spoken a word when Brett and Pier assured they’d make room in their booth.

“(Robertson) says, ‘Well, how long should this be?,” recalled Dave Pier, the chief marketing officer for Brett Sports, the organization that runs both of Spokane’s minor league franchises. “We said, ‘Well, it’s a lifetime contract, Bob. You tell us when you don’t want to do it anymore.’”

Robertson spent 12 years with the Indians, calling four Pacific Northwest League championships before stepping away from the club in 2010. Those in the organization still speak to his diligence and work ethic and assure few in his position take the steps to prepare for a game as Robertson did.

But, for all the prep work he did, Robertson wasn’t email savvy, so members of Spokane’s public relations staff would send information guides and stats via fax to his local FedEx shop in the Tacoma area.

“He’d always call in February or March starting to look for background on who might be in the Rangers farm system because he did such tremendous research,” Pier said.

On that same front, Brett, the club’s managing partner for more than 20 years, added “when Bob first showed up, I was absolutely amazed how much homework and background he did before he even showed up in Spokane on those players. So, we’d get our roster and Bob would come into town a few days before the season started and he had notes after notes after notes on these guys. Then he was looking forward to meeting these players, but he already knew 80% of their backgrounds. Who they dated in high school. It was amazing how much homework he did on a day-to-day basis.”

Another unknown gem from Robertson’s tenure with the Spokane ball club?

“One of the funny things, when Bob came into the league one of the things he wanted is, not every press box had a bathroom,” Pier said. “So, we had to tell him one of the teams that didn’t have a bathroom was moved out of the league. He said, ‘Well, there’s good news and bad news: they’re not in the league anymore, but on the other hand, the team that took their place has a bathroom in the press box.’ So, he was pretty excited.”

Fifty-two years of tales similar to that one came flooding back when news of Robertson’s death spread Monday morning.

When Price finished postgame interviews with Robertson, the play-by-play announcer usually invited another assistant coach to the press box for a short conversation on the record.

Because the assistants often tried to skirt the interview, Robertson sweetened the pot, offering $5, $10 or even $20 to anyone who’d talk.

“I talked after the Apple Cup when we were ahead and lost in the last seconds of the game with (Jim) Sweeney,” said Price, recalling a game in the 1970s when he was an assistant. “I’d have paid twice that much not to have to go up there and talk to him.”

Robertson, who served as the voice of Notre Dame football for two years in the 1950s, dabbled in boxing, hockey, hydroplanes and Major League Soccer.

He was also the longtime voice of Division III Pacific Lutheran basketball.

Robertson is survived by his four children, Hugh, Janna, John and Rebecca, along with his seven grandchildren.

To the day to he died, Robertson spoke with unequivocal adoration for his late wife, Joanne.

“I know Bob really missed her,” Pier said. “I’d think we’d all like to think they’re back together.”