Civics lesson: 70 years ago, a new constitutional amendment created presidential term limits

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: The president of the United States can only serve two terms. Why?

A two-term president enjoying his authority and wanting another term has a likely insurmountable obstacle: the 22nd Amendment, which was ratified 70 years ago on Saturday.

For most of this nation’s history, there was no constitutional obstacle.

Back in 1787, the framers at the Constitutional Convention debated for the first time officially what the office of the president would look like and how it would function. When the topic of term limits came up, it may be surprising to hear that some fathers of democracy like Alexander Hamilton and James Madison argued for lifetime tenure for presidents, a policy that George Mason derided as elective monarchy.

An early draft of the Constitution limited the president to a single seven-year term, but this divisive issue, with framers lobbying for numerous other options, eventually came to a compromise. The president would serve a four-year term, but there was no limit on how many terms a president could serve.

As a result, the framers decided that someone could theoretically be president for decades if he or she kept winning re-election. It gives the impression that a president could become the second coming of King George III, but they were also not guaranteed more than four years.

Today’s two-term limit actually started when the framers were still around. When George Washington was nearing the end of his second presidential term, he felt that two terms were probably enough for a president, with historians saying he was just plain tired after winning the Revolutionary War and leading a nation still in development.

Washington stepped down after his second term, even though he could have won re-election easily. Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the U.S., further established the tradition by also declaring his intentions to end his presidency at two terms. The second president, John Adams, didn’t get to decide whether to serve a third, or even second term. He was unpopular at the end of his first term and lost a re-election bid to Jefferson.

And then president after president who won re-election stepped down instead of running for a third term, turning Washington’s decision into a strong precedent.

There were a few exceptions over the years. Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson all attempted to run for third terms, but none had a realistic chance to win the presidency: Grant and Wilson failed to win their party’s nominations and bowed out, while Roosevelt ran unsuccessfully as a third-party candidate.

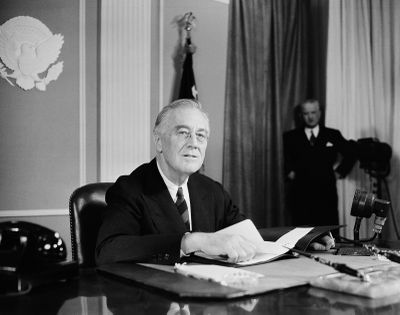

Then came Franklin D. Roosevelt, and nearly 150 years of precedent was tossed aside when he decided to run for his third term in 1940.

Roosevelt had a strong argument for his third term. The U.S. still was facing the lingering effects of the Great Depression and the Nazis were beginning their invasion of European countries – dual crises that he argued should be handled by an incumbent with experience. And with no constitutional limit, Roosevelt was free to pursue and win his third presidential term in 1940.

And why stop at three? Roosevelt won another term in 1944, much to the chagrin of Republicans who had already endured 12 years of a Democratic president.

“Four terms, or 16 years, is the most dangerous threat to our freedom ever proposed,” said Thomas E. Dewey, the 1944 Republican presidential nominee. But voters disagreed and decided to keep Roosevelt in the White House.

After Roosevelt died a couple of months into his fourth term, in April 1945, his vice president, Harry Truman, proceeded to finish his term. Republicans, who won both the House and Senate in the midterm elections in 1946, set out to amending the Constitution to make sure something like Roosevelt’s extended tenure could never happen again.

Finding some Democratic support, Republicans passed the 22nd Amendment in Congress in 1947 and sent it to the states for ratification, which happened when it was approved by Minnesota on Feb. 27, 1951.

The amendment stipulates that “no person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice,” but does not say that no person can ascend to the presidency more than twice. A former vice president who became president could run in two presidential elections, which would mean more than eight years in the White House.

For example, Lyndon Johnson served out President John Kennedy’s first term after Kennedy was assassinated. Then Johnson won his own first presidential term, and could have run for a second, but decided against it due to the tensions of the Vietnam War.

But there are limitations for those who ascend to the office upon the death or resignation of the president. The amendment says: “No person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once.”

The timing of Kennedy’s death toward the end of his term made Johnson eligible to run for a second full-term in 1968 had he opted to.

If the 22nd Amendment had been in place when Teddy Roosevelt considered it for the 1908 election, he wouldn’t have been eligible because he had served well over two years of William McKinley’s term after McKinley was assassinated.

Presidents who have been elected twice could be a bit crafty if they just can’t kick the leadership bug.

A former two-term president could try to become a vice president and then make the argument that they can become president again if the president whom they serve under vacates the office. John Hudak, a senior fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution, was confident that this loophole is bunk.

“I think the history of this constitutional amendment would suggest that the Congress wanted a president to be done after two terms,” said Hudak. “And so, the idea that Barack Obama or George W. Bush or Bill Clinton could become vice president, it just doesn’t really stand up to history.”

But the loophole has not been tested so experts can only speculate if it could actually withstand a legal challenge. There seems to be a very small, but non-zero, chance that we could see a modern-day Roosevelt.