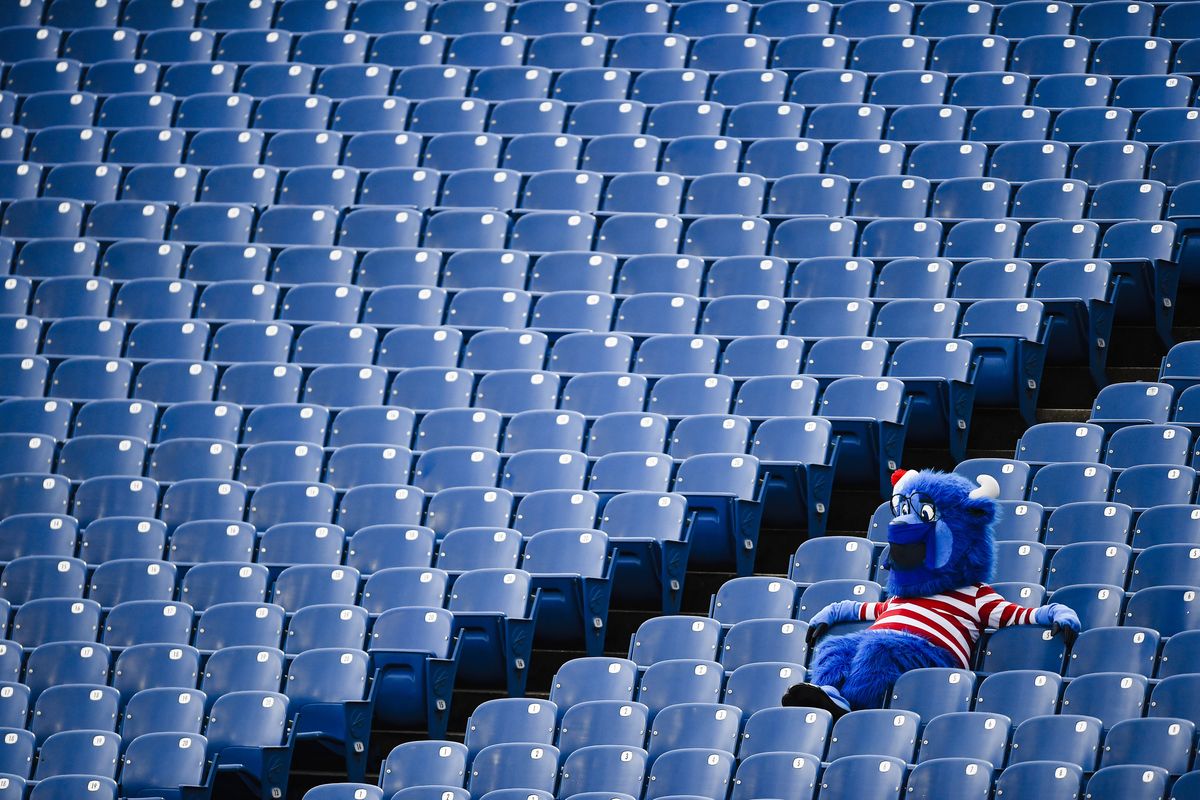

A tribute to lonely mascots, the most surreal symbol of sports in 2020

SEATTLE – The most surreal symbol of sports in 2020 is arguing with a cardboard cutout three rows behind home plate. It is attempting to convince a smiling, life-size photograph of a fan to join in “The Wave” inside an obviously empty Citizens Bank Park. It is 6-foot-6 and 300 pounds – with bright-green fur, bushy blue eyebrows and “a slight case of body odor,” according to its bio. It is a flightless bird from the Galapagos Islands – but it looks like a pear-shaped bush that waddles when it walks. It wears a white jersey, a red hat and an unblinking expression. It does not wear pants. It does not need pants.

Its pleas – er, gestures? – fall on deaf ears. Or, more accurately, on no ears at all.

It is the Phillie Phanatic, baseball’s most beloved mascot.

And, besides the players, it is literally alone.

Which, of course, conflicts with a mascot’s calling. According to A.J. Mass, an ESPN writer who assumed the massive head of Mr. Met from 1994 to 1997, “the whole point of a mascot – not to get on a philosophical level – but they pay you to entertain the crowd. If there’s no crowd, what are you doing there?”

In 2020, COVID-19 caused an existential crisis – mascots without the masses they were made to entertain. MLB’s 60-game sprint was played exclusively in empty stadiums. The NBA, WNBA and NHL all embraced makeshift bubbles, while the NFL and college football allowed varying numbers of socially distanced spectators.

The mascots, meanwhile? They struggled to adjust.

“This whole watch-from-home thing was great until I got a noise complaint for blasting ‘Bow Down to Washington,’ ” said Harry the Husky, the University of Washington’s anthropomorphic mascot, in an actual statement provided by the school. “They must be friends of Butch T Cougar.”

Added the Mariner Moose in a written release (since suited mascots are, and always have been, universally nonverbal): “Every day I’d come out to the field hoping to see fans, especially kids. And while it was great to see the thousands of pictures of everyone, it just wasn’t the same! I did have more time to do things outside the ballpark, and being able to see people all around town was great. And, I got a lot better at doing video conferences. Luckily for me, it doesn’t matter if I forget to unmute myself!”

For some mascots, the experience was especially muted. Take Gritty, the Philadelphia Flyers’ 7-foot fever dream of untamable orange fur. Like his fellow mascots, Gritty was not allowed inside the NHL’s postseason bubble. And, when the league’s shortened 2021 season was announced last month, it included a glaring mascot omission.

“Hockey is back!” Gritty tweeted to his 356,000 followers on Dec. 21. “I couldn’t help but notice that (NHL commissioner Gary Bettman) left mascots out of his big announcement yesterday. @NHL you kept me out of the playoff bubble last season but I DEMAND admission to Flyers games this season. Hockey needs me, I need hockey, the world needs Gritty.”

Later, he added: “I’m depleted. I need to refuel my soul.”

To do that, he launched a change.org petition, which garnered 14,730 signatures as of Wednesday afternoon. Kevin Hayes, a seventh-year Flyers center, also tweeted that the NHL has a “big decision to make! If @GrittyNHL is not allowed in the building for games then I don’t think I can play this year! #GetGrittyIn”

Two days later, the league officially acquiesced, granting Gritty NHL arena access. It was a rare victory for the smiling, wide-eyed instigator.

Still, what must life be like for a mascot in an eerily empty arena?

Well, that’s simple.

“Sheer insanity,” Mass said.

Of course, it wasn’t always this way. In fact, mascots were once associated with a different form of entertainment altogether. The word was popularized thanks in part to the 1880s French opera “La Mascotte,” in which a struggling farmer is visited by a mysterious woman named Bettina – and, upon her arrival, his crops suddenly spring to life. “Mascot” subsequently became slang for a good luck charm.

Which is how the earliest mascot incarnations made their way into sports. There was “John the Orange Man,” a bearded man who sold fruit at Harvard in the late 1800s. It was bad luck to bet on a game that John didn’t attend. Yale’s “Handsome Dan” – the first live mascot in collegiate sports – served a similar purpose. The bulldog – owned by a member of the crew and football teams in the class of 1892 – was led across the field prior to major sporting events “to bestow confidence and prosperity upon the athletes,” according to the university’s official website. There have since been 17 other Handsome Dans.

But only one Max Patkin.

In 1944, Patkin – a former minor league pitcher – was serving in the Navy and stationed in Hawaii, when Yankees superstar Joe DiMaggio homered off him in an exhibition game. In a moment of self-deprecating inspiration, Patkin trailed him around the bases in an exaggerated trot.

And so, “the clown prince of baseball” was born. For five decades, Patkin drew crowds to games across the country – converting the mascot from a glorified rabbit’s foot into a marketing tool.

Mr. Met made his debut in 1964, and the San Diego Chicken hatched a decade later. The Phillie Phanatic – designed by Bonnie Erickson, creator of the Muppet Show’s Miss Piggy and Statler and Waldorf – unfurled its extendable tongue for the first time in 1978.

“Certainly the chicken and the Phanatic go on the Mount Rushmore, as the ones who took mascots into the modern era,” said Mass, who published a book called, “Yes, It’s Hot in Here: Adventures in the Weird, Woolly World of Sports Mascots,” in 2014.

Soon enough, the modern era made its way to Seattle. The Mariner moose roller- skated onto the scenle in 1990, and Harry the Husky joined the fray in 1995. Blitz – Seattle’s best-dressed Seahawk – flapped his feathers for the first time in 1998, and Doppler – the Storm’s resident red blob – popped onto the radar to complete the quartet.

(Squatch, the Sonics’ stunt-obsessed sasquatch, is gone – for now – but not forgotten.)

Together, they established themselves on the Seattle sports scene – teetering on a tightrope between the fans and the team.

“The mascot still lives in this sort of limbo between the two worlds,” journalist Roman Mars said in his podcast, “99% Invisible,” in 2015. “He’s not quite part of the team, but not quite part of the fanbase either. I think that’s the power of a mascot. What fan of a team wouldn’t want to be able to have that freedom to mock the other team and get a response? They live vicariously through the mascot.”

In the mascot, we suddenly see ourselves. Who among us has not felt alone, detached, disconnected from the people and passions that propel us through life? Who hasn’t yearned for the once-familiar comforts of our routines before the pandemic?

In that sense, then, we are all the Phanatic. We are all Harry the Husky and the Mariner Moose. We are all Zippy the Akron Kangaroo, and Jaxson De Ville the Jacksonville Jaguar. We are all Ephelia, Williams College’s proud purple cow. We are all the trampoline-dunking Suns Gorilla. We are all Sammy, the banana slug from UC Santa Cruz, and Arsenal’s Gunnersaurus the green dinosaur. We are all Cayenne, the hot pepper from Louisiana-Lafayette, and Nordy – a mullet-wearing mascot of the Minnesota Wild.

Coronavirus or not, we all need community.

And, sooner or later, we’ll refuel our souls.