Idaho First Lady brings helping hand, ‘good karma’ to North Idaho woman recovering from addiction

Here's my full story from Sunday's Spokesman-Review:

By Betsy Z. Russell

At 25, Brandi Irons has accomplished a great deal. She is raising a young son while holding down a job at the Kootenai Recovery Center, and recently completed her first semester in a social work program at North Idaho College earning a 3.7 GPA.

It wasn’t always so. Irons has struggled with drug addiction since she was 13, been incarcerated three times and emerged from multiple rehab terms, only to relapse. Her climb has been a long one.

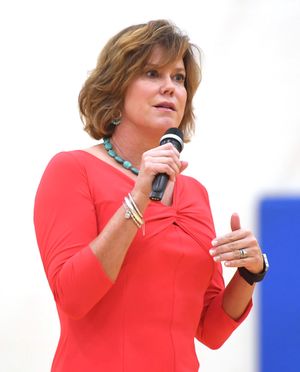

And she owes part of her current success to an unlikely source – Idaho First Lady Lori Otter. In October of 2016, Irons and Otter were on a panel together at the Kroc Center in Coeur d’Alene when the first lady heard the young woman’s story.

She was moved and offered to pay for her schooling.

“She seemed at a place where a helping hand could really turn things around and help her to continue to believe in herself as much as those who meet her believe in her ability,” said Otter, who is the founder of the Idaho Meth Project and a longtime activist for preventing teen drug use.

“I had no idea who she was, honestly. … It was my first panel that I had ever been on, so I was very nervous,” Irons said. “At the end she was like, ‘Where do you work?’”

At the time, Irons was working at a call center, but she said she wanted to be a counselor “and help youth like me, because my counselors helped me a lot when I was getting clean.”

Mrs. Otter asked the young woman if she’d applied for any counseling jobs, and Irons said she hadn’t – she still needed to go to school to recieve a certification.

“And she said, ‘I’ll pay for your school,’” Irons said. “She repeated herself and said, ‘I’ll pay for you to go to school.’”

“She followed through and I started my first semester in January,” Irons said.

Mrs. Otter paid for Irons’ classes at NIC, which cost $1,500 a semester, and all her books. “She was like, ‘Whatever it takes, I’ll be there,’” Irons said. “She followed through, and I’m still kind of in shock, honestly.”

Otter and her husband, Gov. Butch Otter, are multimillionaires. They’re also well-known philanthropists, but have always done their giving quietly.

“It’s not giving if you are keeping score,” Lori Otter said.

A former school teacher, Otter has made teen drug addiction a top cause during her husband’s three terms as Idaho’s governor. “Drugs and addiction rob people and children of their free will,” she said. “The world is hard enough without drugs messing families up and continuing cycles of dysfunction.”

Irons’ parents divorced when she was 13, and “I didn’t know how to handle (the divorce) at the time,” she said. “So I turned to drugs and alcohol. I started smoking pot, drinking at age 13, and of course it escalated quickly. And then I had a full-blown opiate addiction by the time I was 15.”

After several minor brushes with the law, she landed in jail on five felony charges – including distribution, manufacturing and possession of drugs – in 2013. She was 20 when she was charged, and 21 when she was imprisoned.

“At the time, I thought it was the worst thing that ever happened to me, but it turned out to be my lifesaver,” she said.

There were many more fits and starts ahead of her on her journey.

Released on probation, she immediately started using again and went back to jail. She went through Coeur d’Alene Pastor Tim Remington’s addiction program, and graduated in March of 2014, but relapsed again shortly afterward and headed to prison on a six-month “rider,” a retained jurisdiction program that sent her to the Boise Women’s Correctional Center.

“I was really positive about not hanging out with old friends and staying clean, and I never wanted to do that again,” Irons recalled of her release. “And that lasted for about two weeks. Then I started hanging out with my old friends again, started getting high again.” In March of 2015, she was picked up for a probation violation.

“While I was in jail, I found out I was pregnant with my son,” she said. “So praise the Lord that I went back to jail and didn’t keep using, because that would have negatively affected him.”

She was sure she was headed for a long stint in prison this time. But instead, she was diverted into Kootenai County’s drug and mental health court program. “I got into that while I was five months pregnant, I was living in a homeless shelter,” Irons said. “It was good for me, because I didn’t know how to live on life terms.”

“I could go through any treatment facility in the world and just pass with flying colors, but when it came to being out on my own, I didn’t know what I was doing,” she said. “I had been using since I was 13.”

With the mental health court, she said, “I had so much support.”

There was still one more relapse, while she was living in a transitional house with her son. That earned her a week in jail.

“I have done a total of 15 months locked up. That one week was worse than all 15 months combined,” Irons said. “I got out on Christmas Eve, and I got to spend Christmas with my son. And I vowed never to let something like that happen again. And I have been clean since Dec. 13, 2015.”

She began doing community service at the Kootenai Recovery Center, and ended up getting a job there. She’s now a certified recovery coach and peer support specialist, and says she is looking ahead to a career helping others and providing a good life for her son, Niko, who’s 20 months old.

Asked why she offered to pay for Irons’ college – including a two-year associate’s degree program at NIC followed by two years to finish a degree in counseling at Lewis-Clark State College – Otter said, “Because I can afford to help – she needed it, and really, do I need another purse?”

“She was a really neat kid who was nervous about public speaking and telling her story,” Otter recalled. “I got the sense that she realized it would be hard but a necessary part of helping her recovery process.”

Since then, Irons has spoken on several other panels.

“I went home and I was like, there is no way that this is going to happen,” Irons recalled. “I’ve done some horrible things in my life, and there is just no way that this good karma is coming to me right now.” But, she said, “We kept in contact, and she was all for it. I signed up for the classes, I got all the paperwork she needed.”

“I think Brandi is a capable smart gal who is facing her problems, holding herself accountable and has realized she is not alone in the world,” Otter said. “She can help others learn from her mistakes. She should be extremely proud of herself.”

Asked about her message for others facing issues with drugs and addiction, Irons said, “Just keep doing the next right thing – that’s what I would tell them. God will provide always, and if we keep doing the next right thing, something good is going to happen eventually. You can’t always expect necessarily to get your college paid for, but good things are bound to happen if you’re doing the right thing.”