Travel: Reims is the Center of Champagne and History

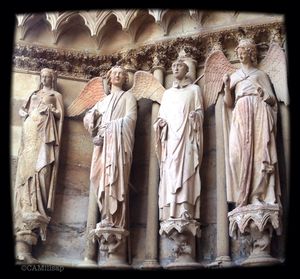

In September, after taking the TVG high-speed train from Paris to Reims, I toured the city’s exquisitely restored cathedral, painstakingly put back together after the devastation and wanton destruction of the First World War. I walked all around town looking at the grand Art Nouveau and Art Deco architecture of the rebuilt city. I sat at a table at a small cafe and watched the people stroll by.

I’d come to the city to see the landmarks and tour WWI battlefields and cemeteries, doing research for the 2017 Centennial of the entry of the Untied States to the war that had already cost Europe the best of a generation. But Reims sits in the heart of France’s Champagne region—the thing that draws most tourists—and is home to some of the finest champagne houses. I may have been there to study history but I wasn’t going to miss a chance to sip a little bubbly.

Taittinger, founded in 1932, is actually one of the newer champagne houses but its cellars are in some of the oldest of the region’s deep chalk caves. During the worst of the First World War the caverns were a place of refuge. They were put into use as a school and hospital, as a shelter during the relentless bombardments. But their history is much older than that. The caves were dug by Romans who quarried the bountiful chalk. In the 13th Century the caves housed the Saint Nicaise Abbey. You can still see the high arches supporting the caverns and the narrow stone leading up out of the caves.

Our guide led us through the long subterranean corridors, past rows and rows of champagne bottles aging in wood racks or stacked into deep alcoves and he pointed out graffiti scratched into the soft walls. Once you become aware of it, the names, dates and rough sketches are everywhere. They are permanent reminders of the fear, fatigue, anger, love and longing that were carved into the man-made rooms that had sheltered men, women and children during the war.

The year 1918—the year the war ended—was scratched in one place, a woman’s profile in another. Around one corner I could see a “pickelhaub” the derogatory name for a German soldier’s dress helmet during WWI, the one ornamented with a spike at the top.

I tried to imagine what it must have been like to be sheltered there: the ordinary sound of people, of children’s voices; the whispers, coughs, and cries of the wounded. Moving from one small pool of light to another, in such long ribbons of darkness, would have frightened me.

The Taittinger cave tour gave me a new appreciation of the ancient history of the land and the strength of the French during the long hard years of war and reconstruction. The Taittinger champagne tasting after the tour only renewed my appreciation for the way the French make wine, especially Champagne.

Cheryl-Anne Millsap’s audio essays can be heard across the Northwest on Spokane Public Radio and on public radio stations across the country. She is the author of 'Home Planet: A Life in Four Seasons' and can be reached at catmillsap@gmail.com