Some pot prosecutions in doubt

OLYMPIA -- Prosecutions in some marijuana cases are grinding to a halt in Washington, a result of a glitch in a new law, a lack of equipment at the state crime lab and the basic chemistry of the oft-discussed weed.

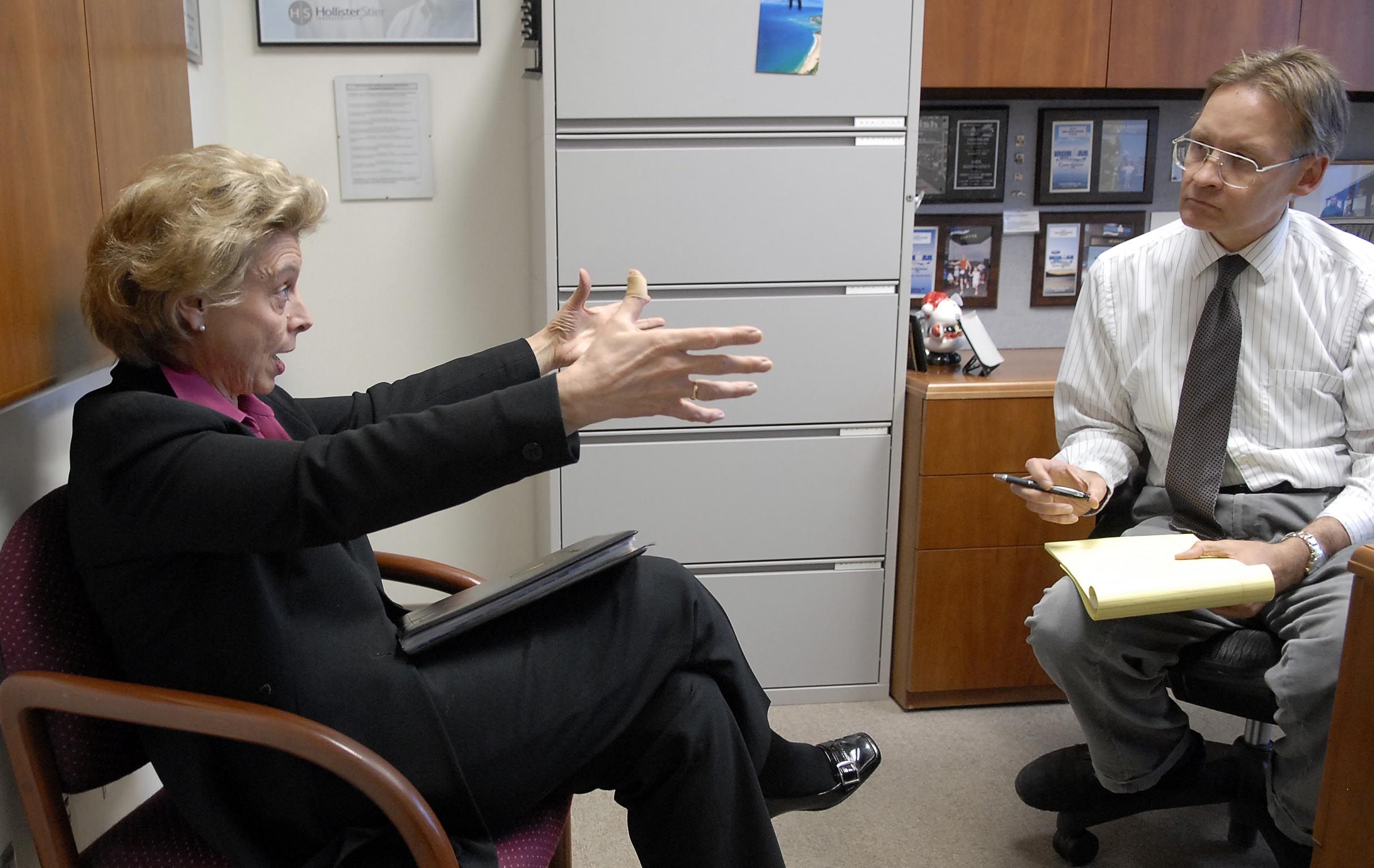

The Washington State Patrol Crime Laboratory can't say for sure that material seized in growing operations, drug buys or major possession cases meets the new definition of illegal marijuana, King County Prosecutor Dan Satterberg told the House Government Accountability and Oversight Committee Thursday.

"We can't enforce the law," he said.

Prosecutions for people who smoke marijuana or eat it in baked goods, then get arrested for driving under the influence, aren't affected because the lab tests are different.

In an attempt to correct the problem, the committee approved a bill to change the definition of marijuana approved by voters last year in Initiative 502. It added an emergency clause, which would mean the law went into effect immediately if passed and signed by the governor.

"Obviously, this is something we need to act on now," Chairman Chris Hurst, D-Enumclaw, said.

But House Bill 2056, which was just introduced Wednesday, would have to pass both houses with a two-thirds majority before the session ends on Sunday, or be part of the likely special session.

Hurst said he couldn't speculate on the bill's chances. The committee did its job by sending it to the House for further consideration, he said. But if legislators don't pass the law before going home for good, marijuana possession cases might not be prosecuted for the rest of the year.

To understand the problem, the committee got a science lesson in the chemistry of marijuana from an array of laboratory analysts, attorneys and medical marijuana experts. . .

To read the rest of this item, or to comment, click here to continue inside the blog.

. . . There are different varieties of the cannabis plant, they were told. Marijuana varieties are grown for high levels of delta-9 tetrahydracannibanol, the psychoactive substance that produces the "high." Hemp varieties are grown for their fiber and oil content, and have low levels of that chemical, but do contain a precursor, tetrahydracannibanol acid, or THC-A.

Before I-502 passed, that wasn't a problem, because both marijuana and hemp were illegal, and the presence of any type of THC was enough to prove the substance was illegal. Under the initiative, however, marijuana is defined by the content of delta-9 THC; it doesn't mention THC-A.

THC-A turns into delta-9 THC when a marijuana plant dries after harvest, is heated, burned or baked into food. The machine the state lab uses to test plants seized for grow operations or major possession cases heats the material to obtain a reading. An analyst can't say on the stand how much of the delta-9 THC in the test results was THC-A in the original product.

"We don't have the ability to isolate delta-9 materials from THC-A materials," Satterberg said.

Alison Holcomb, the author of I-502 and drug policy director of the state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, said the initiative used language that is common in other countries and wasn't intended to let illegal growers or sellers avoid prosecution. But if she were defending someone in a marijuana case "I would pick at every evidentiary opportunity I had."

This isn't a problem for people arrested for driving under the influence of marijuana because that's based on a blood test for a certain level of delta-9 THC in the body.

Questions about test results came as news to defense attorneys in Spokane. Public Defender John Rodgers and private attorney Frank Cikutovich both said they hadn't heard about the potential problems with lab tests that could affect cases involving growing, sellling or possessing marijuana.

The state could buy different testing equipment, known as a liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer, that would test the seized material without heating it. But that would require training for the technicians, and the tests are time intensive.

Other countries where marijuana is legal and industrial hemp is grown use those testing machines and differentiate between the two chemicals. Rather than spend the money for new testing equipment, the bill would change the law to say the total content of THC-A and delta-9 THC could be used to determine whether seized material was marijuana.

The cost of an LCMS was debated at the hearing, with state lab officials saying one costs at least $60,000. The state would be better off spending the money for other equipment that would help ease the backlog on DNA testing, Satterburg said.

Steve Sarich, an advocate for medical marijuana, said one could be picked up on e-Bay for as little as $7,500, and the state doesn't need to regulate THC-A, which isn't a psychoactive drug.

Reps. Matt Shea, R-Spokane Valley, Jeff Holy, R-Cheney, and Cary Condotta, R-East Wenatchee, voted against the bill. If Washington wants to allow farmers to start growing industrial hemp along with state-regulated recreational marijuana "we're going to have to get this equipment."