Boy saved by town to graduate today

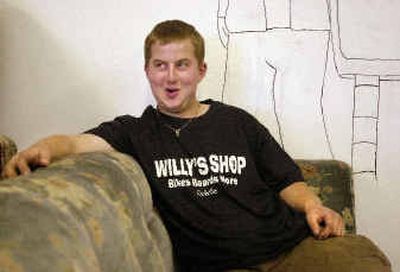

COLVILLE – Nick Thresher, the frail kindergarten boy it took a village to save, is graduating from high school today.

The boy who wasn’t expected to live is now a young man who charges down Colville Mountain on a heavy-duty mountain bike and scales rock walls with his girlfriend. He works part-time as a bicycle mechanic, and plans to begin college this fall.

His mother calls it a miracle.

Thresher, 19, remembers little of the bone marrow transplant that nearly killed him while saving his life 12 years ago. But he remembers the “Nickels for Nick” campaign that helped make it possible.

“If you start to think about it at all, you feel there are definitely a lot of people that care for you,” Thresher said. “They’re good-hearted people who want to make a difference.”

As a kindergartner, Thresher spent more time in hospitals than in class and was near death. He suffered from a rare blood disorder, called Evans syndrome, that caused his immune system to destroy his blood cells. Only about a half-dozen people in the nation were believed to suffer the disease at the time.

His doctor, Spokane hematologist Frank Reynolds, determined that a bone marrow transplant was Thresher’s last hope for survival. But the Thresher family’s insurance company, Qual-Med, refused to pay because a marrow transplant apparently had never been used before to treat Evans syndrome.

Then, in January 1992, the village intervened.

Elementary school students collected “Nickels for Nick,” middle-school students had a cake walk with pizzas and high-school students went Christmas caroling for cash. Police officers played exhibition basketball to raise money, and other adults passed the hat at work.

Eventually, hundreds of people throughout the Inland Northwest joined the campaign to save a little boy most of them didn’t know. They raised about $57,000, enough to cover staggering out-of-pocket expenses that would have bankrupted his family.

“People were so wonderful. It makes me cry even now just thinking about it,” said Nick’s mother, Diane Backstrom. “We were fairly new to the community. It was very unexpected, and it was just amazingly kind of people to come through like they did.”

Although extraordinary, the contributions were still far short of the quarter-million dollars needed for a bone marrow transplant.

It just didn’t seem right to Hofstetter Elementary teacher Carol Monasmith’s third-grade class that Qual-Med wouldn’t pay. One of Nick’s older brothers, Zach, was in Monasmith’s class and Nick, then 6, sometimes came along when their mother was a class volunteer.

“He was kind of a class mascot,” Monasmith recalled. “He was just so sick. It looked like he wasn’t going to live.”

The class had just studied Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement when Qual-Med said Nick Thresher’s bone marrow transplant was an experiment it couldn’t pay for. So the kids launched a letter-writing campaign.

Excerpts from those letters – including their misspellings – were published in a front-page story in The Spokesman-Review. “He needs your monny,” the headline read, quoting a letter in which Robert Davis advised Qual-Med that “a little six year old boy shouldn’t be thinking about dieing.”

“You act like he’s only thin air,” classmate Julie Smith told the insurance company.

Classmate Josh Sampson thought Qual-Med executives should pay or go to jail. Others offered more subtle but equally powerful messages.

“What would you feel like if you had a son or a daughter that was about die, and the insurance company won’t pay?” Ryan Wolfe asked. “Could you just find it in your heart to save someone’s life!”

Three days later, Qual-Med announced it would pay, having discovered that a bone marrow transplant had been used to treat a condition similar to Thresher’s.

“That was such a great lesson for the class,” said Monasmith, who figures her students’ letters had more to do with the decision than new information did. “It showed them that one person can make a difference in another person’s life.”

Thresher barely survived the grueling transplant, in which his faulty immune system was destroyed with chemotherapy so it could be rebuilt with stem cells from his brother Zach. Now, though, Thresher has outlived Qual-Med – which went out of business several years ago – and every other Evans syndrome patient.

Bone marrow transplants are now the standard treatment for Evans syndrome, according to Thresher’s mother, who went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in nursing. She now works in a Colville medical clinic.

Nick still has to take steroids, although in far smaller doses, to keep his immune system under control. He is susceptible to infections, and spent much of last summer battling pneumonia.

“That wasn’t cool,” he said. “I couldn’t go swimming or anything.”

He also suffers chronic sinus problems and – occasionally – arthritis-like joint pain. Thresher said he thinks his major medical problems are solved and the rest amounts to “fine tuning.”

His family also has faced hardships over the years. His parents divorced in 1996, and his eldest brother, Jeremy, vanished without a trace about three years ago. Jeremy was a student in Bellingham and fell in with a bad crowd, Nick said. Police don’t know what happened, but think Jeremy may simply have chosen to disappear, his mother said.

“It’s a very hard thing,” she said. “I just don’t know what to do.”

Zach is working as a timber cruiser for the Forest Service in Eureka, Mont.

Nick said he had lost contact with his father, Cliff Thresher, but they’ve started seeing each other again.

He sees a possible career in graphic design and advertising, which springs from the interest in photography and videography he developed at Colville High School. For his senior project, he spent 27 hours making a 30-second television commercial for Willy’s Shop, the bike-and-board business where he was hired a couple of weeks ago after hanging around there for three years.

Although many of his classmates are eager for brighter lights, Thresher said he wants to stay in Colville as long as he can. People probably get bored in Seattle, too, and they have to go a lot farther for mountain biking, he reasons. So he plans to do his basic college courses at the Community Colleges of Spokane branch here.

Thresher also acknowledges a debt to the community.

“I’ll have to figure out a way to give that back somehow,” he said.