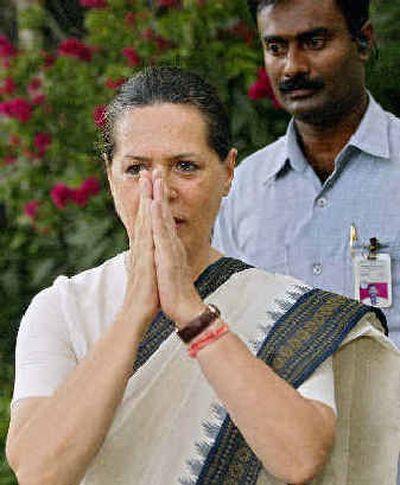

India’s leader concedes defeat

NEW DELHI – She first claimed the spotlight as the prime minister’s wife, then as his widow. Now Sonia Gandhi will try to forge a coalition that could thrust the Italian-born opposition leader into the office her slain husband once held.

Results coming in Thursday from India’s five-stage parliamentary elections gave Gandhi’s Congress party a wide enough lead that her rival, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee, conceded defeat – a stunning upset. Gandhi also won her Parliament seat.

“She will be the prime minister – hundred percent,” Congress party general secretary Ghulam Nabi Azad said. “For stability it is necessary that the prime minister be from the single largest party, that is the Congress party and our candidate is Sonia Gandhi.”

If the Congress party does lead the next government, it would only be able to do so in an alliance with other parties. Some have not made clear that they would accept Gandhi, who would be India’s first foreign-born prime minister.

Most observers had predicted that the ruling alliance led by Vajpayee’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party would easily sweep to victory again, riding a surging economy, good monsoon rains and a public relations campaign celebrating what they called “Shining India.”

As for Gandhi herself, the BJP had hammered on her foreign origins, saying her Italian birth should keep her from becoming prime minister.

It was an argument she dismissed.

“They have so totally failed that they have to pick up this one issue,” Gandhi, who became in Indian citizen in 1983, said in a rare television interview in February.

She told New Delhi Television that her foreign birth might work against her with some, but that in rural areas – especially among women and the poor – she was no outsider.

“I never felt they look at me as a foreigner,” she said. “Because I am not. I am Indian.”

A woman who had long tried to stay out of politics, Gandhi, 57, was thrust into national prominence with the 1991 assassination of her husband, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Seven years later, Congress party officials desperate for a prominent name to help rebuild their stumbling party coaxed her into taking over its leadership.

Slowly, she became an important presence in Indian politics, and has traveled constantly in her campaign to return the party to power.

But she remains shy to the point of near-reclusiveness, and while she now regularly gives speeches in her Italian-accented Hindi, she almost never gives interviews or press conferences.

The daughter of a small building contractor and raised in a conservative Roman Catholic family outside Turin, Italy, Gandhi came to India as a 21-year-old bride.

She married into a dynasty that had dominated Indian politics since independence from British colonial rule in 1947.

Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, headed the country from independence until his 1964 death. He was followed by his daughter, Indira Gandhi, a woman chosen by party leaders because they felt they could control her, but whose often iron-fisted rule defined the next two decades of Indian life.

Whether intentional or not, Sonia Gandhi reminds many Indians of her mother-in-law: the way she wears her sari; her habit of forcefully striding ahead of her aides; the way she stretches out her arms to adoring supporters.

Indira Gandhi was killed by her own bodyguards in 1984, and her son Rajiv, an airline pilot and Sonia’s husband, was reluctantly forced to take the political spotlight.

In a memoir about Rajiv, Sonia wrote that she “fought like a tigress” to maintain the family’s privacy he was pulled into national prominence.

Riding a wave of public sympathy over his mother’s killing, Rajiv won the following election with an unprecedented majority, but his attempts to open India’s stagnant economy and shrink its bloated bureaucracy cost him a lot of his popularity. He lost power in 1989, and was killed two years later while campaigning.