Once-favored Iraqi ally severs U.S. ties

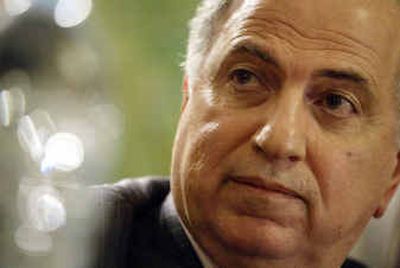

BAGHDAD, Iraq – Ahmad Chalabi, the Iraqi Governing Council member who was once the linchpin of the Bush administration’s ambitious plans for a new Iraq, said Thursday that he’s severed ties with the U.S.-led coalition after a morning raid at his mansion in Baghdad.

Chalabi told journalists his relationship with occupation authorities was now “non-existent” after American soldiers and intelligence officers sent Iraqi police inside his home to confiscate computers, weapons and other equipment.

A senior British official with the coalition said the raid was conducted to arrest as many as 15 people on charges that “involve fraud, kidnapping and associated matters.” Chalabi wasn’t among those named in arrest warrants. The official added that coalition forces oversaw the raid on Chalabi’s home and two offices of his influential Iraqi National Congress party, but didn’t participate in the searches.

Chalabi’s colleagues on the U.S.-appointed Governing Council condemned the raid, a move that could mean American administrators would lose other Iraqi allies six weeks before they hand over limited sovereignty to an interim government.

Until recently, Chalabi and his INC enjoyed unusual access to neoconservative officials in the Pentagon and Vice President Dick Cheney’s office and to some Republicans on Capitol Hill. Chalabi and his group provided much of the information on which the administration built its case for war and the Pentagon built its plans for war and for postwar Iraq. Four months ago, Chalabi sat behind first lady Laura Bush in the House of Representatives gallery during President Bush’s State of the Union address.

But in recent months, three senior administration officials told Knight Ridder on Thursday, four concerns led Bush, National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice and some of Chalabi’s former allies in the administration to lose faith in the former exile. All agreed to speak only on the condition of anonymity because the president dislikes public reports of dissension in his administration.

The concerns:

• Allegations of what one of the senior officials called “rampant corruption” by some of Chalabi’s allies and underlings in Iraq, including stealing cars, demanding bribes from companies that sought to bid on contracts with Iraqi ministries, questionable banking activities and seizing houses and other properties.

The allegations, widely known in Baghdad, were undermining support for U.S. efforts in Iraq because Chalabi was generally considered America’s closest Iraqi ally. “Chalabi was killing us,” said one senior official in Washington.

• Intelligence suggesting that Chalabi’s security chief, Arras Habib, had what one top official called “contacts with the more nefarious creatures in Iran.” Other U.S. officials said Habib might have given Iran information about American military activities and political plans in Iraq.

• A campaign by Chalabi to undermine United Nations special representative Lakhdar Brahimi’s efforts to form an interim government by June 30, when the United States has vowed to return limited sovereignty to an Iraqi government.

Chalabi also irked U.S. officials when he tried to launch his own investigation of the United Nations’ oil-for-food program, refused to turn over files the INC seized from Saddam Hussein’s intelligence services and bitterly opposed a new U.S. policy to rehabilitate some members of Saddam’s Baath Party.

• Mounting evidence that Iraqi defectors supplied by the INC fed the administration exaggerated, fabricated or unproved information on Iraq’s illicit weapons programs. Chalabi also assured U.S. war planners that Iraqis would greet U.S. troops as liberators.

The officials said support for Chalabi in Washington has largely evaporated. “You never hear his name anymore,” said one senior official.

The Iraqi National Congress was informed last week that the $335,000 monthly payments it has received from the Defense Intelligence Agency would stop in June. The INC received $33 million from the State Department from 2000 to 2003, according to a General Accounting Office report on Thursday.

In addition, two senior U.S. officials said, Pentagon officials or contractors who they said had been living intermittently in Chalabi’s compound and serving as back-channel liaisons between Chalabi and the office of Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, “have moved out.”

Sen. Sam Brownback, R-Kan., once a leading supporter of Chalabi, said Thursday that he hadn’t spoken with Chalabi in two months. Chalabi has been “nettlesome to a number of people,” said Brownback, an original sponsor of the Iraq Liberation Act, which helped fund Chalabi’s INC.

Rumsfeld wouldn’t comment Thursday when a reporter asked if he’d lost confidence in Chalabi.

“He is seen now as much more of a problem for the U.S. than a solution,” said Iraq expert Anthony Cordesman of the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Iraqis rank Chalabi as one of their least-liked politicians, but in an apparent effort to boost his support, Chalabi has become increasingly critical of the U.S.-led coalition. He said Thursday’s raid was payback for his calls to keep Baathists out of the government, investigate alleged bribery in the oil-for-food program and return full control of the armed forces to Iraqi leaders.

“I am America’s best friend in Iraq,” Chalabi said. “If the CPA finds it necessary to direct an armed attack against my home, you can see the state of relations between the CPA and the Iraqi people.”

“My message to the (Coalition Provisional Authority) is: Let my people go,” he told reporters. “We are grateful to President Bush for liberating Iraq, but it is time for the Iraqi people to run their affairs.”

Dan Senor, a coalition spokesman, said the raid was based on intelligence from the Ministry of Finance. The ministry is overseen by Chalabi supporters and has been accused of funneling money to the INC, according to a coalition official speaking on condition of anonymity.

An Iraqi criminal courts judge speaking on background described eight people, including security chief Habib, as “outlaws” wanted for torture, kidnapping and stealing cars from the former regime for personal use.

Neither Chalabi nor U.S. officials could confirm whether any of them were in custody.

Chalabi said he was asleep at 11 a.m. when Iraqi police barged into his bedroom of his pagoda-style home in Baghdad’s wealthiest neighborhood.

Chalabi said officers helped themselves to fruit and cartons of Pepsi before kicking in doors and breaking a picture of his grandfather. News photographs taken after the raid showed ransacked rooms and a framed portrait of Chalabi with a bullet hole in the head.