Seattle woman awarded Nobel prize

SEATTLE – Figuring out how the nose can detect thousands of odors won’t cure cancer, but one of the scientists who won a Nobel prize for groundbreaking research on the sense of smell says it could lead to breakthroughs in treating disease one day.

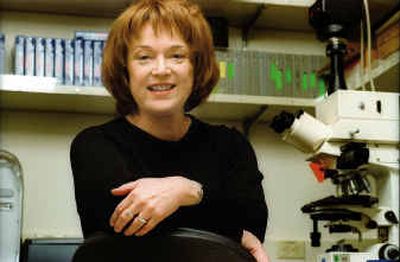

“You do basic science research to understand mechanisms and know – it’s absolutely certain – that from those basic mechanisms will come information that’s critical to treating disease,” said Linda B. Buck, a researcher at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

Buck and Richard Axel, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biophysics at Columbia University in New York, won the $1.3 million Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine on Monday for discovering the molecular basis of smell.

Until Axel’s and Buck’s findings were published in 1991, little was known about how people can recognize and remember 10,000 or more odors. Neuroscientists figured “receptor” proteins in the nose fed information to the brain, but it wasn’t clear exactly how it all worked.

Axel and Buck, then a postgraduate fellow in Axel’s lab, discovered a family of about 1,000 genes devoted to producing different odor-sensing proteins, called receptors, in the nose.

They found that those genes gave rise to the same number of olfactory receptor types – 1,000 in the mice they studied. Before that, scientists could only guess at how many different receptors were needed to distinguish smells in the environment.

Scientists now know that people have about 350 types of odor receptors, each of which can detect only a limited number of odors.

Buck and Axel showed that odor-producing molecules are recognized by different combinations of receptors in what they called an “odorant pattern.”

She compared that pattern to the way letters in the alphabet form words.

“You put letters of the alphabet in different combinations and you have different words, so similarly you can put these different receptors together and get different smells,” Buck said.

While their findings don’t have any immediate practical applications, Buck said unlocking clues in one sensory system could give new direction to research on other systems.

“As you learn more about how the brain functions in one system, then those principles that are uncovered may very well apply to other systems,” Buck said.

Buck, 57, joined Fred Hutchinson in 2002 after 11 years as a faculty member at Harvard Medical School. Mark Groudine, director of the cancer research center’s general sciences division, recruited her.

“Linda is extremely intelligent and creative, but she also just hones in on a subject and gets to know everything about it,” Groudine said. “Our philosophy in basic science is to hire great people and turn them loose.”

Buck grew up in Seattle, got an undergraduate degree in microbiology from the University of Washington, and said she returned to her stomping grounds in part because she sensed her research would be zealously supported.

“There’s a culture of science without politics here, and a real desire and a devotion to doing excellent science and uncovering the basic mechanisms underlying biology,” Buck said.

The daughter of an electrical engineer, she remembers resisting her father’s pleas to build toy motors and wonders if her mother’s love of puzzles led to her fascination with the intricacies of microbiology.

Early on in her career, Buck was focused more on immunology and said her interest in studying the sense of smell started when Axel told her she’d have to study neuroscience if she were to work in his lab.

“I read a little about it and I thought this is very difficult,” she said. “Maybe in 20 years a lot of headway will be made in understanding the immune system, but it might take 100 for the nervous system. But it was very interesting, so I went there.”

At one point, she started reading up on research into olfactory receptors and got hooked on the idea of finding where they were and how they worked.

“I became completely obsessed with finding the receptors, which in retrospect was a potentially suicidal obsession,” she said, drawing laughs at a news conference attended by two other Nobel laureates from Fred Hutchinson.

Lee Hartwell, the center’s president and director, won the Nobel in 2001 for his work in yeast genetics. Dr. E. Donnall Thomas, director emeritus of the center’s Clinical Research Division, won the prize in 1990 for his work on bone-marrow transplantation.