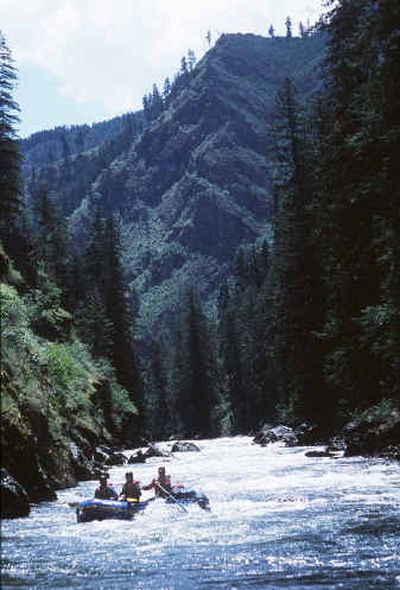

Idaho’s Selway River a revered waterway

Rivers are the blood vessels of a wilderness area. They are the life lines that link the ecosystem and provide the arterials for fish, wildlife and adventurers alike.

The Wild Rogue in Oregon, the Wenaha-Tucannon in Oregon and Washington and the (Salmon) River of No Return in Idaho are examples of wilderness areas named for streams that have carved a critical role in the region’s viability and culture.

None is more revered than the namesake of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, an area that was among the first no-brainer listings for protection under both the Wilderness Act and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act.

Competition for whitewater permits to float Idaho’s Selway River is second in the continental United States only to the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon. Floaters who applied to the Forest Service in February for the lottery drawing faced 31 to 1 odds in snagging one of the 55 private group permits offered for the prime season this year.

The odds on the region’s other top wilderness rivers are 29 to 1 on the Middle Fork Salmon, 9 to 1 on the Salmon and 3 to 1 on the Snake.

In addition, four outfitters are allowed a total of 16 launches a season on the Selway. They charge about $1,500 a person for five-day guided trips that generally book up with more than a dozen clients each.

The trips center on 47 of the river’s 90 miles, a roadless section featuring about 45 named rapids of Class II or higher. Most notable are rapids such as Goat Creek, Ham, Double Drop, Ladle, and Wolf Creek, which range to a puckering Class IV or higher depending on the water level.

From Paradise Guard Station to Selway Falls, the river plunges an average of 28 feet per mile. However, the Selway’s two major distinguishing factors are the solitude — only one party is allowed to launch each day — and the dearth of recovery pools or eddies in major stretches of rapids.

Once you launch into this section, the chances of getting help are limited to the rafters that might come a day later, a few scattered lodges, airstrips, the Moose Creek Ranger Station or the occasional pack string plodding along the trail that sometimes offers a view of the river.

On some days, you’re likely to see more black bears than people.

Dave Campbell, the Selway-Bitterroot National Forest West Fork District ranger, said the policy of allowing only one launch a day dates to the late ‘70s, when solitude was listed as a key plank in the Selway’s wilderness management. Other rivers, including the Middle Fork Salmon, allow multiple launches each day.

The Selway, combined with the adjacent Frank Church-River of No Return and Gospel Hump wilderness areas, total 3.9 million acres to form the largest block of designated wilderness in the lower 48 states.

Yet no Forest Service rangers check boaters for safety gear at the Selway put-in as they do on most of the other major wilderness permit rivers.

“Along with the solitude, there’s a higher degree of responsibility here,” said Barry Miller, the Selway River ranger for the past 20 years.

The way the river changes from mile to mile, day to day and storm to storm is another defining characteristic, Miller said.

When the snowplows first open the Forest Service access road over Nez Perce Pass in late April or early May, the river is low and ice cold. It rages as most rivers do for a few weeks of runoff and settles through the end of the wilderness rafting season in July, when there are more rocks than water showing in the upper stretches.

But no matter what stage the river’s in, the flow changes dramatically as you float downstream because of the streams feeding the river from the enormous watershed, Miller said.

“Below Moose Creek, the river will be more than twice the volume at the put-in,” he said.

But I was confident as I joined a group of Missoula-area rafters who had drawn a permit. Getting a call from an old college buddy to fill a slot on such an exclusive and coveted adventure was a dream-come-true, especially considering the group’s credentials.

“This is basically the same group that got the permit and went down the Grand Canyon last year,” assured Ed, my companion for numerous muscle-powered adventures. “They’re all experienced rafters.”

Our permit was for the last week in June, normally a period when the river can still be quite high and scary. This year, however, the runoff had tapered quickly in early June, although not soon enough for one party.

On June 5, Oregon rafter Gail Sparwasser, 58, drown in the Selway after the 14-foot raft rowed by her husband flipped in either Double Drop or Ladle rapids. She was wearing a full drysuit, lifejacket and helmet, but she was still overcome by the combination of cold, swift water and a constant pounding in that boulder-strewn section of the river.

“The river was at 3.8 feet when they put in, but down where the accident happened, it was in the 6-foot range,” Miller said. “That’s not unraftable, but it’s big, dangerous water.”

Sparwasser was the first river-running fatality on the Selway since 1996. Forest Service officials say modern raft designs, more acceptance for wearing safety gear and higher skill levels have dramatically improved the river’s safety record since 1990, the last of three consecutive years for fatalities.

The river had dropped to 2.7 feet at the put in when we loaded our rafts, zipped up our wetsuits and launched from Paradise. The lower flow had throttled back some of the river’s power, but exposed more rocks and made some stretches trickier and more technical.

I had full faith in the group, though, and I even strapped my fly fishing rod to be accessible for any opportunity to cast for the river’s fabled native cutthroat trout. The river flows were just coming down from the best whitewater range and into good fishing conditions.

“There goes Brian,” said Ed after we pushed off second in the flotilla of five rafts and one kayak. “He can really read the rapids. He’s the guy we want to follow down the river.”

Then, within seconds of Ed’s soothing observation, for no apparent reason, Brian was ejected from the raft by a little wave I wouldn’t hesitate to let a toddler take on in a little rubber duckie.

“Whoa!” I said.

Ed chuckled a nervous what-the-hell’s-going-on chuckle and the four of us in his raft squeezed a little tighter on our paddles.

For the first four days, there was no time to put down the paddle and pull out the fishing rod while on the river. Such diversions from safe navigation in our paddle raft were possible only at lunch breaks or in the evening, as the group made camp on isolated beaches and fanned out to explore the river on trails, some of which were maintained only by elk and moose.

The rafters snapped into a quick routine of unloading boats, pitching tents, setting up the kitchen and finding a private spot with a spectacular view for the “groover,” which is a misnomer for a group that’s prissied up to a tank toilet with a comfy round seat.

Like soldiers of foreign wars, veteran rafters distinguish themselves with sobering stories of sitting on the old open ammo box that left two temporary creases in their butts.

Seasoned river rafters are surprised the Selway has no regulations requiring floaters to use fire pans to keep beaches clean of ash or to pack out human waste.

Whitewater rafters have readily complied with those rules on rivers such as the Salmon, Snake and Grande Ronde.

“I was an advocate for those requirements when I first came here,” Miller said. “But in 20 years I’ve seen the user ethics evolve and I don’t think the rules are necessary. Our objective is to keep the management plan simple. We limit the use more than other rivers and we’re probably getting 95 percent compliance on fire pans and potties without a regulation.

“Most people have realized they like a clean camp when they get here, and they leave it that way.”

Indeed, the river gathered more speed and power as we traveled downstream, much to the amazement of Rick, my partner in the front of the paddle raft.

“It seems like whenever you go somewhere you keep asking, ‘Are we there yet?’ ” he observed. “But on the river, it’s like, ‘Hey, are we here already?’ “

We spent considerable time stretching our legs near Moose Creek, hiking and dodging rattlesnakes up to Shissler Peak Lookout for a view of the vast wild expanse we were penetrating, and later hiking downstream to check out the first couple of big rapids we’d encounter in the next stretch, known as the canyon section.

“The Class IV’s come pretty fast down there,” Ed said.

We’d eddy out before each rapid, scout the stretch and make a plan for negotiating the haystacks, holes, boulders and bends. Then a calm would come over the group as each raft focused on the challenge ahead, erupting dripping wet in brief celebration after each success.

Finally, on the last half of the fifth day the river calmed enough to allow fly rods to come out as we drifted. We looked for chinook salmon that had negotiated hundreds of miles of the Columbia, Snake and Clearwater rivers before making huge air-borne leaps to scale Selway Falls and swim into the wild Selway to spawn.

The river was so calm we could hear a winter wren serenading on shore and contemplate the bears we’d seen in the water upstream.

The wilderness river that had consumed us was now letting us go.