The one Ichiro’s after

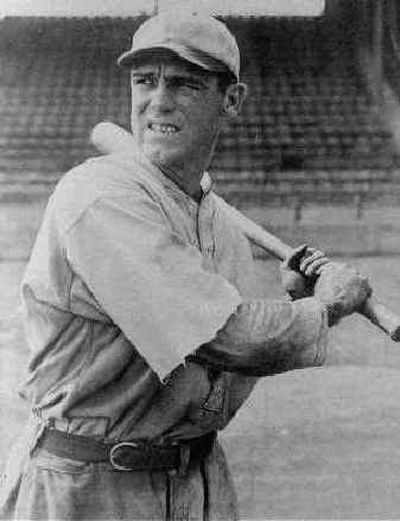

In 1941, George Sisler watched as Joe DiMaggio eclipsed his record 41-game hitting streak, going all the way to 56 games. Now, Sisler’s family is watching as another of his records is threatened.

Right fielder Ichiro Suzuki of the Seattle Mariners is approaching Sisler’s single-season record of 257 hits, a mark that has stood in baseball obscurity since 1920, the year the St. Louis Browns first baseman averaged .407.

Ichiro has 250 hits with eight games remaining.

“My dad would say, ‘More power to him,’ ” says Sisler’s only daughter, Frances Drochelman, 81, of St. Louis. “He appreciated players that worked hard. My dad would say that records are made to be better. My dad was a gentleman, a great athlete and very educated. He never bragged. I loved that about him.”

Sisler is one of baseball’s greatest players, and yet he remains virtually unknown. His career with the Browns started briefly as a pitcher, with Sisler getting two of his five wins against Hall of Famer Walter Johnson. In 1916, the Browns made him a first baseman to take advantage of his hitting.

With the possible exception of Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, Sisler was considered the best all-around player in baseball of his era, says Hall of Fame researcher Gabriel Schechter.

Sisler, a left-handed batter who is considered one of the best defensive first basemen ever, hit .340 for his career and had two seasons in which he hit better than .400. He won four American League stolen-base titles and the 1922 A.L. MVP Award. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939.

Browns fade to black

Sisler faded into obscurity because he was quiet and played for a team that rarely won and eventually moved to Baltimore to become the Orioles in 1954. Also, batters are often judged more by their average than their hit total, meaning Sisler’s record tends to get forgotten, says Steve Hirdt of the Elias Sports Bureau.

“George Sisler was not flamboyant,” Schechter says. “He played for the Browns, who were overshadowed by the Cardinals. He was overshadowed by Rogers Hornsby, and then Ruth and Lou Gehrig. And Sisler wasn’t controversial like Ty Cobb. He was a clean-living, efficient performer.”

After playing eight seasons and hitting .420 in 1922 — the year the Browns lost the A.L. pennant by one game to the New York Yankees — Sisler sat out the 1923 season because of a sinus problem that caused double vision. He returned in 1924 and retired in 1930 with 2,812 hits.

“He had optic nerve problems in his eyes at age 30 in the middle of his prime,” Schechter says.

“He was seeing double. He lost power and just wasn’t the same.”

There is a group of Browns fans in St. Louis that is hoping Ichiro doesn’t erase Sisler’s record.

“If Ichiro breaks the record, the Browns will be left with nothing — except for records like the 1950 game, when Boston scored 29 times against us,” says George Walden, 71, a Browns fan who lives in St. Louis and scouts for the New York Mets.

“I hope you understand why we Browns fans are silently cheering for our hero. It’s all we have left.”

Sisler earned a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Michigan but never used it.

After his career, he ran a sporting goods store, built softball parks, owned a printing company and worked as a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates.

Sisler, who was 80 when he died in 1973, was known as “Poppy” to his family members.

When he was scouting for the Pirates, his family remembers Sisler getting up early after night games, reading the Bible and typing his reports with the hunt-and-peck method on a typewriter.

He and his wife, Kathleen, had four children. In addition to Frances, the three boys were all involved in baseball.

George Jr. was a minor-league executive. Dave Sisler pitched for seven seasons, mainly with the Boston Red Sox, and Dick was a first baseman-outfielder with the Cardinals, Cincinnati Reds and Philadelphia Phillies.

Dave Sisler, 72, who was 16 when he pitched batting practice to Robinson at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, said his father never saw him play baseball or basketball as a youth: “He never wanted to put pressure on me.”

George Sisler, attending an old-timers’ event, saw Dave beat the Yankees in New York one afternoon.

That was the only time he saw his son pitch in the big leagues.

Era error

Ichiro and Sisler are different types of players, and ironically each may have fit better in the other’s era.

Sisler had more than 100 RBIs in four seasons and could hit for power, finishing among the top five in slugging percentage six times.

Ichiro, on the other hand, is a singles hitter playing in an era when players swing for the fences and don’t give strikeouts a second thought.

Dave Sisler says his dad’s single-season hit total would have had an additional 13 hits — for a total of 270 — if he had played in 162 games instead of 154.

“My dad’s record has held for 84 years, so he had a pretty good year that year,” Dave Sisler says.

“My dad was a great person. Most people think that baseball players should be tobacco-chewing guys, but my dad was a straight, straight arrow. It’s a shame that hardly any one knows about my dad’s records.”