Pope helped lift Iron Curtain

Despite having no armies under his command and no weapons to deploy, Pope John Paul II played a pivotal role in one of the 20th century’s greatest geopolitical dramas – the struggle against the Soviet Union’s forceful dominance in Asia and Eastern Europe.

Through public statements, private negotiations and repeated trips to his native Poland, John Paul helped undermine communist rule in his home country in 1989. That event reverberated throughout other Soviet bloc countries such as Hungary, East Germany and Romania, sparking a chain reaction of revolutions and coups, most of them nonviolent. Today, that region is largely free and democratic.

Years later, former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev reflected on the changes that occurred behind the Iron Curtain. “It would have been impossible without the pope,” he said.

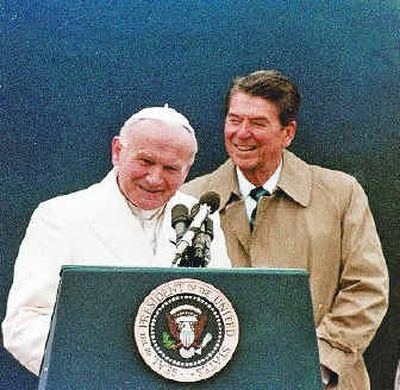

But the pope was not the only force at work in those countries. John Paul’s religious pronouncements complemented the steely will of England’s Margaret Thatcher and America’s Ronald Reagan, combined with years of economic stagnation that made the populations of the Soviet bloc countries eager for change.

The pope’s fierce opposition to communism stemmed from his belief that an individual’s chief allegiance should be to God and one’s own conscience, not the state. The pope thought communism, which suppressed religious, economic and political freedoms, set itself up as a kind of alternative god.

“In our times evil has developed outside all limits,” John Paul wrote in “Memory and Identity: Personal Reflections,” published in February. “The evil of the 20th century was of gigantic proportions, an evil that used state structures to carry out its dirty work; it was evil transformed into a system.”

Some chroniclers of this historical period portray John Paul as one part James Bond and two parts John the Baptist.

While most historians dispute this characterization, few doubt the significance of his contribution to the spread of freedom.

Timothy Garton Ash, an Oxford University historian, put it this way: “Without the pope, no Solidarity. Without Solidarity, no Gorbachev. Without Gorbachev, no fall of communism.”

The seeds of this passion play were sown Oct. 16, 1978. On that day, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla, a relatively unknown 58-year-old prelate from Krakow, was elected pope. Poles poured into the streets in celebration – crying, drinking, and kissing one another.

Seven months later, in June of 1979, the pope returned to Poland for a nine-day pilgrimage. During the trip, roughly a quarter of the nation’s population heard him speak in giant open-air meetings. Millions more in Poland and throughout the world witnessed these events on television.

The pope spoke of Poland’s Christian roots and the transience of the communist regime. His words were a direct challenge to the communist leaders that ruled Poland and surrounding countries with an iron fist that suppressed religion and freedom of speech.

“He gave enormous moral and public support to the opposition and the common man and woman in the street. He morally discredited the regime,” said Anthony Judt, a historian at New York University.

The pope’s tour galvanized the communist opposition in Poland, resulting in the formation of a giant labor union called Solidarity. Led by Lech Walesa, an eventual Nobel Peace Prize winner and Polish president, members of Solidarity struggled against Poland’s communist leaders throughout the 1980s. They assumed power in 1989 after running in the Soviet bloc’s first free election.

Like the first in a row of dominos, Poland’s relatively peaceful transition to democracy led to wholesale change throughout the region over the next year. Soon, the Soviet Union would be no more.

In “Memory and Identity,” the pope claimed little credit for the Soviet Union’s collapse. Instead, he said internal economic rot was largely responsible, even as he pointed beyond economics to spiritual and moral factors.

“It would be rather ingenuous to attribute it only to economic factors,” the pope wrote. “I also know that it would be equally ridiculous to believe that it was the pope who brought down communism with his own hands.”