Attitude adjustment

ST. AUGUSTINE, Fla. – He heard himself called a selfish player, a malcontent, a bad teammate. What really got to Corey Dillon was that for the first seven years of his career he never heard anyone call him a winner.

“For years, I really lost hope,” the New England Patriots running back said as he prepared to play the Philadelphia Eagles in the Super Bowl. “I really thought I’d never get to this stage, but I just kept pressing. … I love going to work and working hard to try to help this organization win.”

Dillon had never been in the playoffs before this year, slogging through in Cincinnati, growing dissatisfied with the losing and the team’s increasing dependence on him to carry the offense. He ran for a then-record 278 yards in a single game in 2000, and he had more than 1,100 yards in each of his first six seasons.

But in 2003, his last year in Cincinnati, he injured his groin and grumbled about becoming part of the “Bungles” legacy of losing. He wanted out, and by that time the Bengals were happy to get rid of him. It was almost unfair when the defending Super Bowl champs – winners of two NFL titles in the previous three years – got Dillon for a second-round draft pick on the Massachusetts holiday called Patriots Day.

Antowain Smith was a steady but unspectacular running back on the two championship teams, and there was no doubt Dillon was an upgrade. But would he fit the team-first attitude of the New England locker room, where dissension is discouraged and going public with your complaints is just not done?

In vetting Dillon with his former teammates, coaches and friends, the Patriots concluded he wouldn’t be a problem at all.

“He was a heck of a player with the Cincinnati Bengals, and he’s been really good with us,” said Scott Pioli, the Patriots’ head of player personnel. “All of us have reputations that precede us. So you sit with a person, man or woman, and find out what and who they are for yourself. We try to avoid judging people before we spend time with them.”

Dillon was concerned enough about his reputation that he addressed his new teammates when he arrived, asking them to keep an open mind. They did, and Dillon thrived in a system in which no single player is the focus of the offense in a locker room where no player is treated like a star.

“Nobody really passed judgment on me,” Dillon said. “I’m pretty sure that it was in everyone’s mind: Let’s see what this guy is all about and see if the rumors are true. But just right off the bat, everyone welcomed me with open arms. Everyone has been great.”

So has Dillon.

He ran for more than 100 yards in nine of 15 games this year – and never for fewer than 79. He missed the biggest game of the regular season, at Pittsburgh, with a thigh injury. Without him, New England ran for 5 yards on six carries and lost to the Steelers on Oct. 31, ending its 21-game winning streak and costing it home-field advantage for the AFC title game.

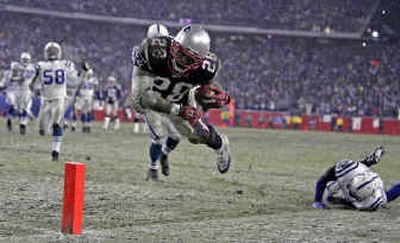

In his playoff debut against the Colts on Jan. 16, Dillon carried 23 times for 144 yards as the Patriots ran Indianapolis out of the postseason, earning him the nickname “Clock-Killin’ Dillon.”

Pacific-10 Conference teams learned about Dillon the hard way in 1996. Dillon set University of Washington single-season records of 1,695 rushing yards, 25 touchdowns and 150 points that year, his lone season with the Huskies.

“You have to hit him. You have to play sound fundamental football” to stop Dillon, Eagles linebacker Jeremiah Trotter said. “He is a big guy. He is a guy who will run hard and try to run over you, but he can break the big one. You definitely have to have a lot of guys around him with the football.”

That opens the field for passes.

“He’s added a great element to this team,” Patriots quarterback Tom Brady said. “He brings toughness to the offense just by the way he runs the ball, and he’s very excited. You can tell in practice.”

Even as he distanced himself from teammates and media in Cincinnati, no one questioned Dillon’s work ethic or his talent. But he recoiled when asked to be a leader in the locker room, and he complained when a groin injury forced him to share the job with Rudi Johnson.

After the last game of his final season there, he threw his pads, spikes and jersey into the stands, then cleaned out his locker. His teammates criticized him, and the Bengals had no choice but to trade him.

Dillon acknowledged he brought to New England “that stigma of being a bad guy in the locker room and being selfish.” But he has maintained he was only worn down by year after year of losing.

“I think the thing that irritated me the most was when they said that I was a cancer to the team. That really kind of ruffled me a little bit,” Dillon said. “For a guy that, for seven years, went out and put his heart and soul on that field, and at the end of the day be looked upon as the reason why we weren’t successful – that rubbed me the wrong way.”