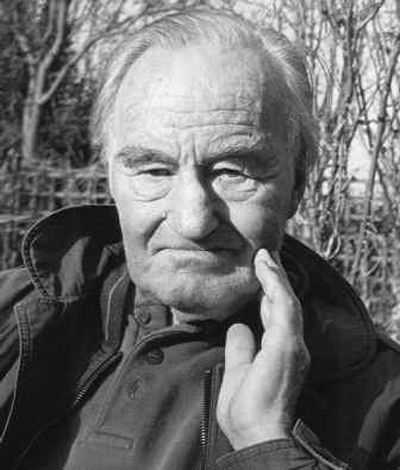

Peter Benenson, the founder of Amnesty International, dies

Peter Benenson, an English barrister whose outrage over the imprisonment of two students prompted him to found the human rights organization Amnesty International 43 years ago, died of pneumonia Feb. 25 in London at John Radcliffe Hospital. He was 83.

Benenson’s organization, which now counts 1.8 million members, won the 1977 Nobel Peace Prize for “defending human dignity against violence and subjugation,” by focusing on human rights and cases of torture and unjust imprisonment around the world.

He launched a movement as well as an organization. Amnesty International is considered the largest of the independent, nongovernmental organizations in domestic and international politics.

As he later said, it started when Benenson, wearing his bowler hat and reading a newspaper on the London underground in 1960, came across a small article about two Portuguese students at a Lisbon restaurant who toasted freedom, were arrested and sentenced to seven years in prison. He wrote an appeal that was sent to the Observer newspaper and printed on the front page, calling for a one-year campaign to address the conditions of six “prisoners of conscience” around the world. Thousands responded.

“He brought light into the darkness of prisons, the horror of torture chambers and tragedy of death camps around the world,” Irene Kahn, secretary general of Amnesty International, said in a statement. “This was a man whose conscience shone in a cruel and terrifying world, who believed in the power of ordinary people to bring about extraordinary change.”

In subsequent years, Benenson remained a modest and self-effacing man, shunning attempts to glorify his role and avoiding personal publicity whenever possible. When the group won the Peace Prize, the organization was represented by its chairman, Thomas Hammarberg of Sweden, not Benenson.

Almost every British prime minister in the past 40 years has offered to recommend him for knighthood, but he responded to each with a personal letter suggesting “if they truly wished to honor his work, they would clean up their own back yard first, and then he would set out a litany of human rights violations the British government was complicit in,” said Kate Gilmore, deputy secretary general of Amnesty International. “It was a clever and inspired pitch, and it was heartfelt. In an era of ego and self-aggrandizement, it was almost hard to conceive that such a man … had such a worldwide impact.”

Benenson’s career as an activist began with a youthful complaint about the quality of food at his school, Eton, which prompted the headmaster to warn his mother of her son’s “revolutionary tendencies.” In his teens, he led his first campaign, to garner the school’s support for orphans in the Spanish Civil War, and he raised money for Jews fleeing Hitler’s Germany.

He studied history for a year at Balliol College, Oxford University, then joined the British Army during World War II, where he worked in the Ministry of Information press office. After the war, Benenson took his bar exams and became a leading member of the Society of Labour Lawyers.

In the early 1950s he was sent to Spain, then under the Franco regime, to observe the trials of trade unionists. Benenson confronted the judge with a list of complaints. The trials ended in rare acquittals. He advised Greek Cypriot lawyers battling the British rulers. He agitated for lawyers to send observers to Hungary during the 1956 uprising. These efforts led to the formation of “Justice,” a British-based legal and human rights group.

Amnesty International began with a simple idea: pressure governments to free political victims by inundating them with postcards and letters from volunteers.

The tactics expanded to include meticulously researched annual reports, press releases and in-person lobbying. The group shows no favor to the West; it regularly criticizes the United States for its military operations and prison executions. Critics have noted that open societies in which information gathering is easier sometimes become the objects of criticism from Amnesty International that is much more severe than such places as North Korea, which does not welcome outsiders investigating human rights.

The organization does not keep statistics on how many prisoners its appeals have freed, partly because it works with many other groups and partly because it prefers to focus on the unfinished work. But there are indicators of success. Gilmore noted that when Benenson began, there were few international legal standards that would hold governments to account for violations of the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but there are now conventions against torture and other egregious acts.

The organization also receives letters such as the one from former Soviet dissident Vladimir Balankhonov, who spent years in a Siberian labor camp. He said his knowledge of the group’s efforts helped him “to remain alive and unbroken despite my uncertainty of what was going on behind the impenetrable barrier of walls and barbed wire surrounding the hell of the gulag.”

Benenson inspired many individuals and the formation of many non-governmental organizations that work on human rights and civil rights of all types. Gilmore called it “this audacious, outrageous conspiracy of hope he contaminated the world with.”

Benenson, who funded Amnesty International in its first years, never stopped organizing. He also founded a society for people with celiac disease, and in the 1980s he became the chair of a newly created group, the Association of Christians Against Torture. In the early 1990s, he organized help for orphans of Nicolai Ceausescu’s Romania.

Survivors include his wife, Susan Benenson; a daughter; a son; and two daughters from a previous marriage.