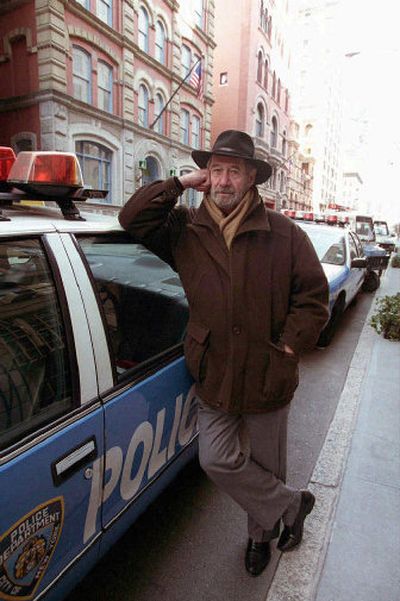

Commissioner of crime genre dies at age 78

WASHINGTON – Author Evan Hunter, who as Ed McBain became the master of the police procedural novel with his “87th Precinct” series and was one of the most prolific and best-selling authors of his day, died Wednesday at his home in Weston, Conn. He was diagnosed with throat cancer three years ago and also had had three heart attacks and triple-bypass surgery. He was 78.

In Hunter’s graphic prose, there were no lone-wolf detectives like Philip Marlowe or amateur sleuths like the country vicar. Starting with “Cop Hater” (1956) and ending more than 50 books later with “Fiddlers,” to be published this fall, Hunter chronicled beat cops, forensic detectives and others in the 87th Precinct as they solve murders, rapes and the range of human miseries in the fictional metropolis of Isola.

Hunter once said that “the only valid people to deal with crime were cops, and I would like to make the lead character, rather than a single person, a squad of cops instead – so it would be a conglomerate lead character.”

If he did not invent the police procedural style, he “single-handedly popularized” it, emphasizing the entire precinct as it went about its work, said publisher Otto Penzler, founder of the Mysterious Bookshop in New York. He dominated the field, Penzler said, having perhaps his greatest influence on television, particularly such shows as “Hill Street Blues” and the “CSI” series.

Despite the sheer volume of his prose, most critics wrote that Hunter’s books remained fresh and inventive, filled with vivid humor, drama and gore. He was said to have written short stories early on to match pulp magazine covers. While he wrote the 87th Precinct novels to illustrate a simple truth – “Cops have a tough, underpaid job, and they deal with murder every day of the week, and that’s the way it is, folks,” he said – he composed dozens of other titles, under several names, touching on far more sensitive themes.

His works of fiction that didn’t deal with police included “The Blackboard Jungle” (1954), his exposure of the educational system; “Buddwing” (1964), about an amnesiac; “Sons” (1969), about the legacy of war in the 20th century; and “Love, Dad” (1981), about failing family ties during the antiestablishment movement of the 1960s. He worked as a screenwriter, notably adapting a Daphne du Maurier short story into Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Birds” (1963).

Hunter was born Salvatore Albert Lombino on Oct. 15, 1926, on his family’s kitchen table in Manhattan. He had hoped to be an artist but turned to writing when he discovered so many of his classmates at the Cooper Union vastly superior in talent and passion. The only child of a mail carrier, he was long practiced at inventing dialogue while playing with his toy soldiers.

He left school to join the Navy and was serving in the Pacific when he began writing in earnest. “I was on a destroyer in the peacetime Pacific, and there wasn’t much else to do,” he once said.

Hunter researched heavily, spending vast amounts of time in squad cars, precinct buildings and in crime labs before writing his first word – efforts that won him vast recognition for the accuracy of his dialogue and plotting and descriptions of body parts on sidewalks and in gutters.

He also relied on some innate ability for invention.

He told an interviewer in 1997: “I have never in my lifetime been on a rooftop in the middle of winter with a Puerto Rican man grieving over a bird that got killed in a cockfight, never in my life. A Puerto Rican man in a pink cotton sweater, dead drunk. … Never.

“But that scene to me is so real, just talking about it now I feel as if I’m on that rooftop, with these cops talking to his drunken guy who’s just confessed to killing someone, their hands hovering near the butts of their revolvers.”