Last ride for Greenacres cowboy

This is how rodeo cowboys honor their dead, by leading a riderless horse into the arena with a hat on its saddle horn and a pair of boots threaded backward through the stirrups.

No one knows how long this tradition has gone on, though it’s rumored that even Genghis Khan’s boots were holstered backward for a final ride in 1227, indicating the warrior wasn’t returning.

John F. Kennedy received a similar honor in 1963 and Ronald Reagan in 2004. Last Friday, it was Ray Ham’s turn.

Ham, a Greenacres cowboy with a Gene Autry smile and John Wayne’s backbone, was honored at the Cheney Rodeo. He died of cancer June 26, four days after complaining that he wasn’t “feeling well,” not ill, or agonized, just not well. It was the kind of response one expected from an 88-year-old man whose sliding scale of discomfort had been tempered by a lifetime of being bucked, bumped, stamped, kicked and even bitten by mammals much larger than him.

He was one tough hombre. Ray Ham didn’t back away from neighborhood toughs. When a repeat felon living down the street from Ham caught the elderly cowboy looking his way and threatened to knock Ham’s block off, Ham simply tightened the grip on his cane and said, “Well, what are you waiting for?”

“He told me later, ‘I don’t know if I could have taken him, but I would have gotten one good hit in with my cane,’ ” said Jason Ham, Ray’s grandson.

It was Ham’s philosophy to approach life, and not just confrontation, head-on. If he had a box of clothes to donate to the less fortunate, he didn’t drop it off at Goodwill. He’d drive to downtown Spokane and look for some downtrodden soul whose wiry frame matched Ham’s and give him the clothes directly, said Janice Austin, who helped Ham compose a biography in the mid-1980s. Inevitably, recipients of Ham’s benevolence received long-sleeved cotton shirts with elongated, sharply pointed collars and mother-of-pearl snaps in place of buttons; the Western-style shirts were all Ham wore.

The book Ham composed with Austin, “Horses & Saddles I Have Known,” was a self-published, 244-page account of the cowboy’s life, beginning in his home state, South Dakota, and ending in Greenacres, where he moved in the 1950s after becoming the outrider at Playfair Race Course. Austin met Ham while looking for someone to shoe her horses.

Thirty years before getting together with Austin, Ham had moved to Greenacres with his wife, Hazel, and sons, Dee and Jay, because they had friends there and Greenacres had hundreds of horses, said Jay Ham. To Jay’s father, it seemed like a good place to make a living shoeing horses and boarding stock.

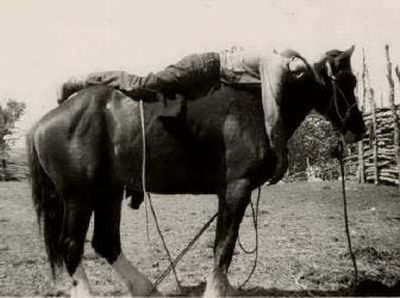

The move was also Ray Ham’s first real attempt to settle down. Ham had traveled the West searching for broncos to ride and wild horses to race. He had a knack for getting the most out of green stock by biting an ear and holding on for dear life.

In between rodeos, he did ranch work and picked peas, but he always put stability aside for the lure of rodeo. Dee Ham said his dad and mom, who died last year, were pros at winning cigar races, which entailed galloping across an arena at breakneck speed while clutching a cigar in your teeth.

Hazel and several other women would be waiting at the other end of the arena to light their rider’s cigar as he rode by. The rider who returned first to the starting point with his cigar lighted won the race.

Being proficient at either bronc riding or cigar racing, or being able to ride a bull, was a sure way to prove your manhood to Ham, a lifetime Rodeo Cowboy Association member.

But few neighbors in the old cowboy’s corner of north Greenacres had ever attempted any of the three. And the few who had made attempts rapidly disappeared in recent years as pastures gave way to duplexes and low-end split-level homes.

The ground constantly shook beneath machines compacting the earth for asphalt. And every pass of the equipment assured there wouldn’t be another Ray Ham, who day by day seemed more out of place in a neighborhood slated for 180 new houses in the next year or so.

In the last years of his life, as neighbors just on the other side of Ham’s rusted wire fence drew up plans for dozens of new homes, the cowboy could be seen in his backyard sitting down with his horse, dog and a longhorn steer he’d agreed to board for a friend, Irv Dust.

But now the steer has moved on; the dog has gone inside. And the horse has no rider.