NASA may launch shuttle even if fuel-gauge problem returns

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. – This will be something of a first:

NASA planned to fuel Discovery overnight, strap its seven astronauts into the orbiter, pray that a baffling fuel-gauge malfunction does not reappear and then press the button today for the first space shuttle liftoff since safety issues contributed to the loss of Columbia and its crew.

Essentially, it will be a combined will-it-work-this-time pre-launch test and real-time launch countdown, a rare event in the history of human spaceflight. Even the relentlessly rational engineers of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration are resorting to superstition.

“No doubt, there is some degree of finger-crossing,” said Pete Nickolenko, a NASA test director who could not recall the last time something like this might have happened.

Even if Discovery fails the test – if the fuel gauge acts up again, as it did during the first launch attempt on July 13 – NASA may proceed with the countdown.

Liftoff from the Kennedy Space Center is set for 7:39 a.m. PDT. The 12-day mission will deliver supplies to the International Space Station and test post-Columbia safety equipment.

On Monday, NASA declared the ship ready to go. Forecasters predicted a 60 percent chance of favorable weather. First lady Laura Bush and other dignitaries were expected to attend.

Former astronaut Winston Scott noted that shuttle components are routinely tested as the countdown ticks toward zero, but it is highly unusual for engineers still to be dealing with an unexplained problem as liftoff approaches.

Nevertheless, given the circumstances, he endorsed the plan.

“I would feel confident strapping into the orbiter knowing these tests are going on,” said Scott, who flew in space twice and now runs the Florida Space Authority. “I think this is a good course of action.”

At issue is a fuel sensor that monitors liquid hydrogen in Discovery’s external fuel tank. A still-unexplained fault in the sensor or its wiring forced NASA to scrub the first launch attempt. The same problem occurred during a fueling test in April.

Four sensors help make sure that the shuttle’s three main engines don’t cut off prematurely or too late. Either of those events could trigger another fatal accident.

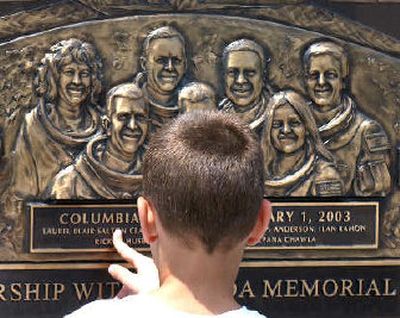

A different problem with the external fuel tank – insulating foam that ripped off and punched a hole in the left wing – caused the Columbia accident in February 2003. All seven astronauts died.

In the wake of Discovery’s scrubbed launch and after unsuccessful study by hundreds of engineers, mission managers decided to switch a few wires, rework three grounding connections, take their tests to the next level by fueling the tank, hope for the best and give it a try today.

NASA flight rules require all four sensors to operate properly, but mission managers said they might permit launch if one sensor fails again and everything else seems fine.

Asked Monday about the propriety of conducting the first post-Columbia mission aboard a ship that might still harbor an unresolved defect, Nickolenko said: “I think that we’ve done an extensive degree of troubleshooting and analysis. … We fully expect that it should work as designed.”