Catholic priest sex-abuse costs $1 billion and rising

The cost to the U.S. Roman Catholic Church of sexual predators in the priesthood has climbed past $1 billion, according to tallies by American bishops and an Associated Press review of known settlements.

And the figure is guaranteed to rise, probably by tens of millions of dollars, because hundreds more claims are pending.

Dioceses around the country have spent at least $1.06 billion on settlements with victims, verdicts, legal fees, counseling and other expenses since 1950, the AP found. A $120 million compensation fund announced last week by the Diocese of Covington, Ky., pushed the figure past the billion-dollar mark.

A large share of the costs – at least $378 million – has been incurred in just the past three years, when the crisis erupted in the Archdiocese of Boston and spread nationwide.

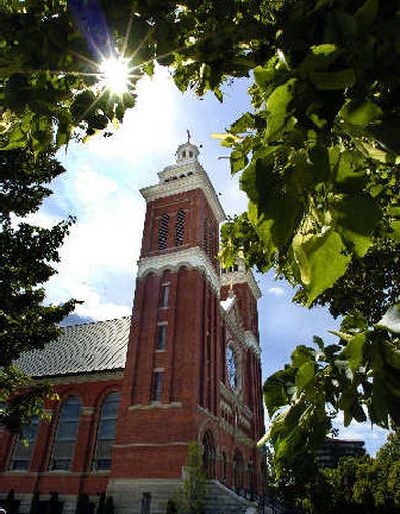

The Spokane Diocese has settled 19 claims during the past 15 years for $1.55 million. And still the diocese has barely come to terms with the onslaught of sexual abuse victims – potentially more than 100 others with claims totaling more than $80 million that forced Bishop William Skylstad to take his Spokane ministry into bankruptcy.

The Spokane estimates do not cover counseling costs, nor do they cover the growing costs of filing Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Already the diocese owes about $1 million to lawyers, and the billing continues.

The Rev. Thomas Doyle, who left a promising career with the Catholic Church to help represent victims, had warned the nation’s bishops in 1985 that abuse costs could eventually exceed $1 billion.

“Nobody believed us,” said Doyle, a canon lawyer. “I remember one archbishop telling me, ‘My feeling about this, Tom, is no one’s ever going to sue the Catholic Church.’ “

Asked about the figure, a spokesman for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Monsignor Francis Maniscalco, said church leaders believe the payouts “should be just to all sides.” He said victims deserve compensation, but the church must also have enough money to continue serving parishioners.

The bishops are set to meet in Chicago next week to review their plan for protecting youngsters.

The exact financial effect on the church is hard to determine, since each diocese owns property separately and settles cases on its own. Insurance policies cover some costs, but policies differ across the country. And in many places, the coverage has run out.

Also, many dioceses already had money problems before the scandal hit, because of rising labor costs, maintenance for old churches and other expenses, said Charles Zech, an economics professor at Villanova University who studies church finances.

However, the church avoided one financial hit: A feared widespread boycott by donors never happened, Zech said. The number of donors has fallen in the past few years, but the amount contributed overall has held steady, he said.

Still, some of the damage is plain.

The Archdiocese of Boston and several others have agreed to sell property to cover their multimillion-dollar settlements. In addition to Spokane, the Archdiocese of Portland and the Diocese of Tucson, Ariz., have filed for bankruptcy, and more are expected to follow.

Though it was the third to seek bankruptcy protection from lawsuits, the Spokane Diocese is embarking on a risky court strategy that could affect how the U.S. Catholic Church uses federal bankruptcy law to manage abuse claims.

On June 27 the Spokane Diocese will defend a long-held stance that Catholic parishes are separate entities from the diocese. Though the diocese holds legal title to parish assets such as churches, schools, trusts and other assets, the diocese maintains it holds the property in trust.

If the diocese wins and withstands appeals, it may signal to other dioceses that bankruptcy is the best way to force all claimants into settlement talks.

Should the Spokane Diocese lose, it may be forced to mortgage or sell parish properties to settle claims, much like a corporation would to settle the claims of creditors.

The billion-dollar cost to the church does not come close to other major legal settlements in recent years. The tobacco industry, for example, has agreed to hundreds of billions of dollars in payouts.

The AP calculated the price from settlement announcements by dioceses and from reports commissioned by the nation’s bishops, including a study by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice of claims from 1950 to 2002. Victims’ groups believe the church reports have underestimated the total cost.

Among religious groups confronting abuse, the Catholic Church is the only one to release settlement figures covering decades. But experts believe that Catholics have paid more to victims than any other denomination. Researchers commissioned by the bishops found more than 11,500 abuse claims against priests since 1950.

Catholics disagree over whether the church is being forced to pay too much for its failures.

Barbara Blaine, founder of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, noted that most recent agreements have been reached before trial – a sign, she said, that bishops know the true scope of the wrongdoing and are trying to minimize the cost.

“That the settlements could go that high shows us the seriousness of the harm and the cover-up,” Blaine said.

But defense attorneys say public opinion has moved so far against the church that the bishops have little choice. Several states extended the statutes of limitation for suing over the abuse; California abolished the time restriction for one year, leading to hundreds of new claims that have yet to be resolved.

Patrick Schiltz, an attorney who has defended many dioceses in abuse cases, agreed that bishops have a moral obligation to pay victims but said the size of the settlements is “getting out of hand.”

The Covington fund is the biggest settlement so far. Last December, the Diocese of Orange, Calif., agreed to pay $100 million to 87 victims. In 2003, the Archdiocese of Boston settled with 552 victims for $85 million.

“It’s because of the media coverage,” said Schiltz, a professor at the University of St. Thomas School of Law in Minneapolis. “The thumb is heavily on the scale against the church.”

Schiltz said he disagreed with Catholics who contend that many of the newer claims are fake. But he said weaker cases that once would have been thrown out of court are probably succeeding.

Despite the rising cost to the church, advocates say the majority of victims never sue.

“Victims want to feel as though their experience is valued, helping the church understand the problem so that it will never happen again,” said Sue Archibald, head of the victim advocacy group The Linkup. “With lawsuits it’s ‘Here’s your money, now go away.’ “