Group hopes to make history with launch of solar spacecraft

A space advocacy group is hoping to show the world a new way to power vehicles through space by launching the first “solar sail” into orbit Tuesday.

If successful, the privately launched Cosmos 1 will pioneer an elegant method of space travel that uses gentle pressure from sunlight to ply outer space.

In theory, the impact of each light particle, or photon, from sunlight on the spacecraft’s sails will propel the probe through space’s airless, near-frictionless vacuum.

The mission is the collaboration of a cast of characters not usually featured in space missions. NASA experts have been consulted, but the Planetary Society based in Pasadena, Calif., is sponsoring the launch of the $4 million experimental spacecraft. Half of the money comes from Cosmos Studios, a maker of science documentaries that is chronicling the mission.

Because fuel takes up much of the weight of modern satellites, solar sails made of stronger modern materials have long captivated space enthusiasts.

If the launch from a submarine in the Arctic Barents Sea goes well, the 220-pound experimental Russian-built spacecraft will reach a 500-mile-high orbit.

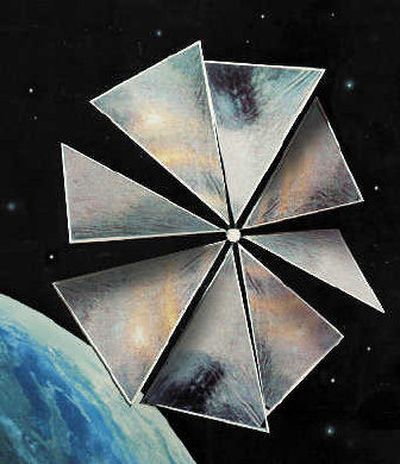

After it circles Earth for four days snapping photos, its eight sail blades, which are made of aluminum-backed plastic about one-quarter the thickness of a trash bag, will unfurl into a 100-foot wide circle.

The unfurling of the sails is the riskiest part of the mission because the material could rip or tangle.

Once the sails unfurl, mission controllers will attempt the first space navigation propelled by the pressure of sunlight. By turning the sail to different angles from the sun’s light, the spin-stabilized spacecraft should be able to raise and lower its orbit.

The sail should be visible at night, shining as brightly as a full moon, but smaller.

The spacecraft should circle Earth once every 101 minutes for weeks.

Sunlight pressure on the sails should be enough to increase the speed of the satellite by only about 100 mph each day, but over time that adds up.