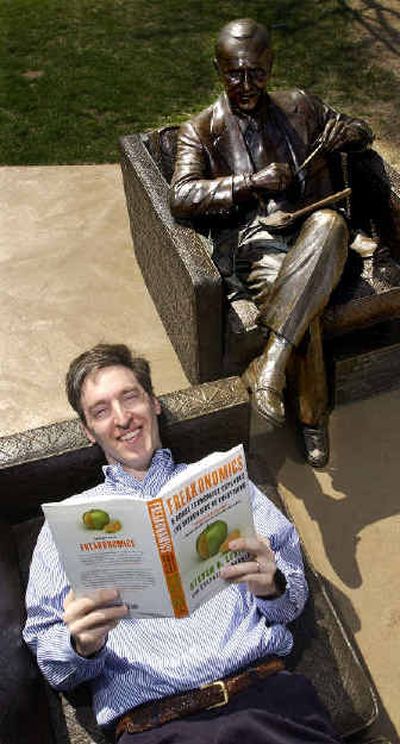

Economist delves into the unusual

CHICAGO — Steve Levitt’s world is economics, but he has no patience for inflation charts or stock market tables. He’d much prefer to plunge into a scholarly study of … cheating sumo wrestlers.

Or slippery real estate agents.

Or drug-dealing gang members.

Levitt is a maverick economist at the University of Chicago, a school known for esteemed scholars.

With a boyish curiosity and a powerhouse resume (Harvard, M.I.T., Chicago), Levitt has explored everything from provocative social issues — linking abortion and lower crime rates — to patterns of ethnic and age bias among TV game show contestants.

“It’s not like I go looking for trouble,” Levitt says. “But I try to find unusual ways to ask questions that people care about. And the most interesting answers you can come up with are the ones that are absolutely true and completely unexpected.”

Levitt summarizes his unorthodox research in a new book, “Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything.” With co-author Stephen Dubner, he details some eyebrow-raising findings:

Guns kill fewer kids than swimming pools.

Gang members may not be mama’s boys, but they often share mama’s house.

Not typical fodder for an economics book — one that manages to mention both W.C. Fields and John Kenneth Galbraith — but that probably helped it climb to No. 2 on Amazon.com’s nonfiction list.

At age 37, Levitt already has compiled some impressive accomplishments: In 2003, he won the John Bates Clark medal, an award given to the leading U.S. economist under age 40 that is regarded by some as a junior Nobel. He has a legion of admirers and his share of critics. And a host of businesses are knocking on his door — everyone from the New York Yankees to General Motors.

Levitt has always been fascinated by corruption and crime. Growing up in Minneapolis, the reality-based “Cops” was his favorite TV show. “Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been attracted to the dark side,” he says.

But young Steve also liked to fiddle around with correlations on a calculator, study stock options in the Wall Street Journal (for his father) and hole up in his room playing simulation baseball board games.

He started out doing economic research on political campaigns, but when that didn’t appeal to him, he says he decided: “I’m just going to study things I like and I’m just going to roll the dice. Maybe it’s going to turn out that other people are going to care and maybe it’s not.”

They cared, all right.

Levitt and John Donohue, then of Stanford University Law School, created an uproar in 2001 when they concluded that legalized abortion significantly contributed to a drop in crime in the 1990s.

Here’s Levitt’s explanation: “Legalized abortion lowered unwantedness. Unwantedness is related to crime, so legalized abortion lowered crime.”

Angry letters poured in. The authors were branded racists proposing a form of eugenics. Levitt insists he was stunned by the reaction and the study made no moral judgments on abortion.

“It never occurred to us that anybody would be upset,” he says. “I’ve done a lot of research. No one ever cares.”

Levitt took on another social issue when he teamed up with another researcher to develop a statistical method that found a small number of Chicago teachers cheated on standardized tests to help their students. Those findings led to disciplinary action.

Levitt is intrigued by incentives — financial, moral and social, good and bad.

And he found them in the wrestling ring.

Levitt co-authored a study that analyzed the won-loss records of sumo wrestlers in tournaments and concluded the matches were rigged. Levitt says he didn’t hear a peep from the Japanese press — even after sending the findings to the Japanese version of the National Enquirer, which had written about corruption in the sport.

Levitt frequently challenges conventional wisdom.

He wrote one op-ed piece concluding a child is 100 times more likely to die in a swimming pool than be killed by a gun.

That work had a poignant origin: Levitt began looking into pool deaths after his infant son, Andrew, died from meningitis and he and his wife attended a bereavement support group, where many parents had lost children in drownings.

Even when his studies might seem trivial, there’s a serious message.

Levitt detected bias on the “Weakest Link,” the game show where contestants vote out a player at the end of each round. He says players tended to see Hispanic contestants as weak, even when they weren’t, and old people as undesirable. He doesn’t point any finger of blame and says players might not even be aware of their biases.

But when it comes to real estate agents, there’s no mistake.

Levitt reviewed tens of thousands of home sales in the Chicago area and found that when agents sold their own houses, they held out longer and got a better deal than they did for their clients.

Levitt has won plenty of press and praise.

“He has a talent for getting data sets that other people don’t have or that other people didn’t think to use,” says Derek Neal, chairman of the economics department at Chicago, where Levitt received tenure after just two years. “He has gifts in terms of creativity that you can’t teach.”

Levitt says he’s sometimes surprised by his findings, including his research of the corporate-like hierarchy of a crack-dealing Chicago street gang. The foot soldiers who risked their lives made so little money they couldn’t live on their own.

Thus, one pithy chapter title in his book: “Why Do Drug Dealers Still Live With Their Moms?”

Strange as it may seem, Levitt says drug dealers reveal economic truths.

“Most of economics is actually about individual human behavior,” he says. “Faced with a set of constraints, what decisions do we make to do the best we can for ourselves? The gang is a great example …. It really is unfettered competition. There are no labor market rules. There are no minimum wages. There’s no workers’ compensation. It is really a market.”

The prolific economist is riding high these days: His book debuted on the New York Times best-seller list last week and VIPs want his ear.

The Clinton administration offered him a job, he says, and President Bush’s campaign approached him about being a crime adviser. He suggested they read his abortion study. “If you’re still interested, let’s talk,” he said. The phone didn’t ring again.

But the New York Yankees and the Chicago White Sox, he says, did call, asking about developing ways to make pitchers most effective against batters. GM wanted to talk about car pricing strategies. Tour de France racers asked him to look into the doping question.

The CIA even had him in for the day to talk terrorism.

“I think it’s better to leave it at that,” he says with a smile.

Levitt is now working with a foreign bank to analyze banking records to catch terrorists. “I think following money is the wrong idea,” he says. “I’m looking at something more mundane — how they use banks, what kinds of transactions they do.”