Mountaineers still out there after 90 years

In the past 90 years, the Spokane Mountaineers have gained a reputation as masters of cheap thrills in the great outdoors.

Car-pooling, sleeping on the ground, potluck dinners, sharing expertise and trading gear for muscle-powered sports have been the foundation of a club that’s left tracks on virtually every notable mountain destination in the Inland Northwest.

More than 220 people, familiar from shared adventures on foot, ski, bicycle and paddle boat, celebrated the club’s anniversary Saturday at a banquet in the Masonic Temple.

Spokane residents Joe Collins, Bill Fixx and Lorna Ream were given an ovation for being active members for around 50 years. Asked how he was able to endure to become the senior-most Mountaineer in attendance, Collins said, “Having a wonderful wife who wants you out of the house.”

The retired jewelry maker joined the club in 1952 and went on to reach 600 summits – 40 of them in the Cascades.

“I never lifted a weight, never ran even across the street, and, except for climbing, I never participated in any exercise other than breathing,” he said.

“And I’ve never owned a down jacket.”

Collins, 80, said he came to Spokane from the East Coast after carefully looking at the outdoor options with a 300-mile radius of various cities throughout the country. “That’s the distance a working stiff can cover and still do weekend adventures,” he said. “And no base offers more options than Spokane.”

Joining a club geared to your interests “instantly puts you in touch with the right people,” he said.

Soon after settling in Spokane, Collins was making a trip to the West Side when he stopped to admire Mount Adams, the biggest mountain he’d ever seen. “I said I’d like to climb that mountain sometime, and my wife said, ‘You can’t do that.’ “

With the instruction and the help of mentors Collins found in the Mountaineers, he was on top of Adams within a year.

“That’s how it all began,” he said. “And everybody agrees that the most dangerous and exciting part of those climbing trips was my driving.”

The Spokane Mountaineers, Inc., was founded as the Spokane Walking Club by five women librarians in 1915.

With renewed national emphasis on physical fitness during the Kennedy administration and the growth of the outdoor recreation industry, the club swelled to more than 300 members in 1971, increasing to more than 500 in 1990 and about 850 today.

As the membership grew, so did the activities.

The club started scheduling bicycling trips in 1935. Climbing instruction started in 1939 and developed into the popular annual Mountain School starting in 1959. The school spans eight weeks and forges the club’s strongest bonds as students and instructors link into rope teams and tackle major peaks, including the annual graduation climb to Alberta’s Mount Athabasca.

The club has a history of fiery board meetings and a tradition of enduring fellowship.

“The interesting thing about Mountaineers is that generally they are extremely independent individuals; on the other hand, they depend on each other with their lives,” said George Broatch in an interview 15 years ago when the club celebrated its 75th anniversary.

Neither gender nor status based on social standing or wealth is an issue in who rises to the peak of esteem among Mountaineers.

Competence and devotion to the group effort singles out the leaders.

Iris Wood, co-leader of the club’s annual backpacking school, said her volunteer time has been rewarded in many ways.

“This year we read in the newspaper about a couple that did a hiking trip across England and they said the skills they learned in our school’s map and compass session saved their lives in a storm. That’s the difference this school can make.”

Scot Nass, a climbing school instructor and master of ceremonies for the banquet, sprinkled the evening with outdoor wisdom, including the Mountaineers mantra: “Cotton is to be forgotten. Stinky polypro is the way to go.”

Collins had learned some timeless lessons, too: “Never climb with a person who has all new equipment.”

Phillip Lindesmith co-organized one of the club’s newest instruction programs. “It’s called the high-angle rock climbing clinic,” he said. “It’s about how to get down when you’re in trouble three pitches up a climb.”

“Been there; needed that,” said a voice from the crowd.

The club also has active groups of skiers and kayakers, as well as an active conservation contingent that has lobbied to protect wild areas from Minnehaha Rocks along the Spokane River to the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness in Idaho.

Collins was one of the members who traveled to testify and lobby for the creation of North Cascades National Park in 1968.

This year alone, club members have rolled up their sleeves to work with groups such as the Backcountry Horsemen to build and maintain trails from the Salmo-Priest Wilderness to the natural areas Spokane County has acquired through the Conservation Futures program.

Jeff Lambert, a conservation committee member since 1997, also serves on the Washington state Nonhighway and Off-Road Vehicle Activities Committee that allocates the 1 percent of the state’s gasoline fuel excise tax dedicated to funding motorized and nonmotorized trail projects.

Asked what the club must do to survive another 90 years, Collins said, “Take care of our natural areas,” another mantra emphasized by some of the club’s best recognized members.

Chris Kopczynski told how he and John Roskelley met in 1967 as teenagers in the Mountaineers climbing school before going on to make climbing history.

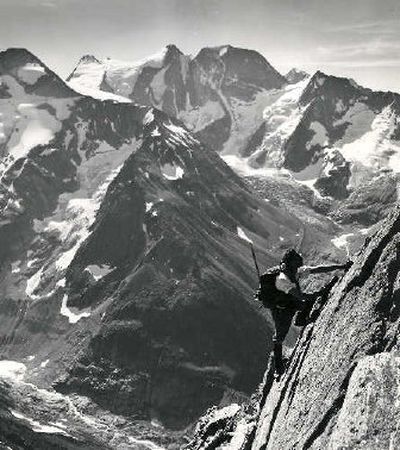

Kopczynski was on climbs that made the first free ascent of the east face of Chimney Rock in North Idaho – “carrying 40-pound packs because we didn’t know any better,” – before joining Roskelley to make the first ascent of Mount Thor in British Columbia. They became the first Americans to climb the North Face of the Eiger in the Alps. Kopczynski later climbed Mount Everest and eventually scaled the tallest summits on all seven continents.

Roskelley, still among the most accomplished Himalayan climbers in the United States, was content to sit back and let Collins and Kopczynski summarize the comedy and drama of Mountaineers climbing history.

“A friend you make in the mountains will be a friend forever,” Collins said. “It’s better than a relative.”

The ballroom often was noisy as Mountaineers caught up with old friends, but the crowd went dead quiet as Kopczynski showed a few dizzying slides and described how he brought an aging Joe Collins off Canada’s Mount Robson on a rope that was looped around a mound he compacted out of snow.

“I didn’t have an ice screw and I didn’t tell Joe that was the only way I had to anchor,” he said. “It was my scariest moment in mountaineering,” he added.

“Except for when he got in the car with me to drive home,” Collins said.