Saved by a vision of future science

RICHMOND, Va. – The forensic scientist cut off the tip of a cotton swab and taped it to a lab sheet next to a snippet of stained clothing.

Always save a piece of what you test, Mary Jane Burton instructed her watchful trainee.

But why? This was 1977, years before the invention of DNA testing. Yet day after day, she repeated this seemingly pointless procedure under the glow of the cramped laboratory’s fluorescent lights – taping swabs smeared with blood, semen or saliva and inserting them into their case files.

Finally, when the ache of arthritis in her hands grew unbearable, she retired from the Virginia state crime lab, leaving behind scores of forgotten files, each holding samples imprinted with nature’s barcode. They remained undisturbed for years, waiting for science to catch up with them – and waiting for someone to discover that they were there.

The bicyclist sat on the side of the tree-lined path, clutching his knee.

He must be injured, the young woman worried when she saw him. She set down the bucket of chicken she’d been carrying home for a late dinner and walked over to help.

The man grabbed her arms and dragged her off the path into a wooded area. For three hours, the woman was savaged – raped twice, sodomized, beaten. The rapist, who was black, told his young, white victim she reminded him of his white girlfriend.

At the same time, in another part of town, a young, black man named Marvin Anderson stood in his mother’s driveway, washing his orange Oldsmobile Starfire. Back at their apartment, Anderson’s young, white girlfriend was preparing dinner.

It was July 17, 1982, and interracial relationships were rare in the small Southern town. It wasn’t long before Anderson was under arrest.

Burton handled the evidence in the young woman’s rape case just like all the others. When she finished testing the specimen on a cotton swab, she cut off the top, took a strip of Scotch tape and secured it to a lab sheet.

At the defense table, Anderson was terrified. How could anyone think he had done such horrible things?

The victim testified that the man who had brutalized her – a monster, she said, who had the eyes of the devil – was unquestionably Anderson. “His face will always haunt me,” she said.

The jury foreman read the verdict and Anderson’s world went black. Guilty. His sentence: 210 years in prison.

Standard procedure in Virginia was for biological evidence to be returned to the authorities after testing. After a few years, it would be destroyed, except in death penalty cases.

Why Mary Jane Burton insisted on saving such samples is a mystery.

On June 18, 1997, after 15 years behind bars, Anderson was released on parole, but freedom was not easy. He had to register as a sex offender. His name was destroyed. He drew whispers and sour looks. Finding work was difficult. In 2001, Anderson’s attorney, Peter Neufeld of the Innocence Project, wrote a letter to Paul Ferrara, director of the state’s Department of Forensic Science, and asked him to dig up Anderson’s case file.

Ferrara opened the folder and idly flicked through the pages, eyes scanning fine lines of type for any indication of when the physical evidence had been returned to the authorities.

Suddenly, Ferrara’s thumb froze. He stared at the blood work report in front of him in disbelief. Scotch-taped to the paper was the tip of a cotton swab – the key to unlocking the truth.

The sophisticated DNA testing that was not available back in 1982 revealed what Anderson and his loved ones had known all along: He was innocent.

In September 2004, the governor ordered the lab to check the archives for more samples Burton might have saved.

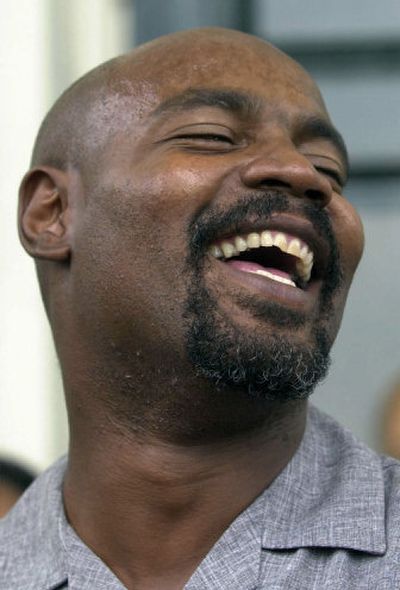

For Anderson, she is a hero. “That woman is a blessing from God,” Anderson said. “She was always looking toward the future.”