Housing fraud on rise

NEW YORK — On a cold, damp February morning, a car with two members of Freddie Mac’s special fraud investigation unit pulled up to 2175 Martin Luther King Blvd. in Atlanta.

What they found further stirred suspicions first raised by an internal report at the U.S. housing agency. The investigators would discover that the building, its yard littered with garbage and broken windows, was the linchpin of a $750,000 alleged real estate scam involving 38 condominium units.

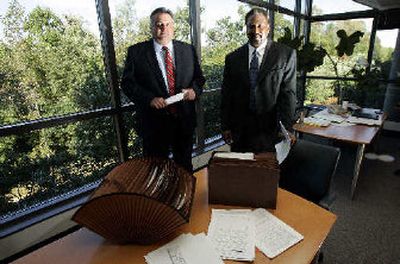

“It just didn’t have very good curb appeal,” quipped Kevin Ludden, one of the investigators. “In a minute you could tell it was a problem property.”

The two men parked their car in back of the building and, after a few words with the maintenance man at the stucco and brick two-story building, they found more clues to fraud that involved a real estate broker, a property appraiser and a closing agent.

“I noticed all the fixtures were missing,” recalled Ludden, who didn’t trust the building’s rickety wooden stairs with his over 6-foot-tall, 290-pound frame. The maintenance man then explained that “he gets a phone call that tells him what units to put the fixtures in so an appraiser can come and take photographs.”

The Atlanta building is still under investigation, but Ludden and his partner believed they had come across a case of real estate fraud, part of a growing problem across the country. Banks and other lenders as well as Freddie Mac, have voiced concern about the growing incidence of fraud, which can have a negative effect on neighborhoods and the market for mortgage-backed securities.

Some of the scams are intricate, while others are primitive. Typically, they involve the mortgage application process and the appraisals required for mortgage approvals.

In one case, a deceased appraiser’s appraisal seal was used by a family member to falsely certify documents, while in another case an appraiser was unaware that her son was using her seal. In another instance, a fabricated appraisal report was accompanied by photographs suggesting a property was in livable condition. The photographs were of the front and rear of a structure, but investigators found that the front of property had been freshly painted and disguised an uninhabitable home.

The photos of the rear of the structure were from an entirely different building and the actual property was gutted, open to the elements.

“It was like a kid’s doll house where you can reach in through the back,” recalled Ludden.

Investigators have also found so-called asset rental companies that promise to lend money to borrowers, who can then claim the money as savings for loan approval. Lenders are then fooled into thinking a borrower has more money than he or she actually does.

Fraud in housing often involves a member of the real estate industry, such as an attorney, broker or appraiser. New loan products that allow borrowers to get mortgages with less documentation about income and savings, so-called lo-doc or no-doc loans, also inadvertently aid fraud.

Some of the fraud does not become evident until loans become delinquent. In many cases, suspicions are only raised when a borrower fails to make any mortgage payments, as was the case with 2175 Martin Luther King Blvd.

As of Sept. 30, the end of the government’s fiscal year, there were 721 pending cases of real estate fraud being investigated, up from 534 in 2004, said Ronda Heilig, a supervisory agent with the FBI’s financial institution fraud unit.

States with heightened incidences of mortgage fraud include: California, Nevada, Utah, Colorado, Missouri, Illinois, Michigan, South Carolina, Georgia and Florida.

“The FBI recognizes these as the top 10 mortgage fraud hotspots,” Heilig said.