Farmers greet Wi-Fi cloud

HERMISTON, Ore. — Parked alongside his onion fields, Bob Hale can prop open a laptop and read his e-mail or, with just a keystroke, check the moisture of his crops.

As the jackrabbits run by, he can watch CNN online, play a video game or turn his irrigation sprinklers on and off, all from the air conditioned comfort of his truck.

While some cities are battling over plans to offer free or cheap Internet access, and others, like Spokane, have established urban “hot zones,” this lonely terrain is served by what is billed as the world’s largest hotspot, a wireless cloud that stretches over 700 square miles of landscape so dry and desolate it could have been lifted from a cowboy tune.

Large providers, such as local phone company Qwest Communications International Inc., see little profit potential. So wireless entrepreneur Fred Ziari drew no resistance for his proposed wireless network, enabling him to quickly build the $5 million cloud at his own expense.

While his service is free to the general public, Ziari is recovering the investment through contracts with more than 30 city and county agencies, as well as big farms such as Hale’s, whose onion empire supplies over two-thirds of the red onions used by the Subway sandwich chain. Morrow County, for instance, pays $180,000 a year for Ziari’s service.

Each client, he said, pays not only for yearly access to the cloud, but also for specialized applications, such as a program that allows local officials to check parking meters remotely.

“Internet service is only a small part of it. The same wireless system is used for surveillance, for intelligent traffic system, for intelligent transportation, for telemedicine and for distance education,” said Ziari, who immigrated to the United States from the tiny Iranian town of Shahi on the Caspian Sea.

It’s revolutionizing the way business is conducted in this former frontier town.

“Outside the cloud, I can’t even get DSL,” said Hale. “When I’m inside it, I can take a picture of one of my onions, plug it into my laptop and send it to the Subway guys in San Diego and say, ‘Here’s a picture of my crop.”’

Even as the number of Wi-Fi hotspots continues to mushroom, with 72,140 now registered globally, just a handful of cities have managed to blanket their entire urban core with wireless Internet access.

But only Ziari appears to have pinned down such a large area.

The wireless network uses both short-range Wi-Fi signals and a version of a related, longer-range technology known as Wi-Max. While Wi-Fi and Wi-Max antennas typically connect with the Internet over a physical cable, the transmitters in this network act as wireless relay points, passing the signal along through a technique known as “meshing.”

Ziari’s company built the towers to match the topography. They are as close as a quarter-of-a-mile apart inside towns like Hermiston, and as far apart as several miles in the high-desert wilderness.

Asked why big municipalities have had a harder time succeeding, he replies: “Politics.”

“If we get a go-ahead, we can do a fairly good-sized city in a month or two,” said Ziari. “The problem is getting the go-ahead.”

“The ‘Who’s-going-to-get-a-piece-of-the action?’ has been a big part of the obstacles,” said Karen Hanley, senior marketing director of the Austin, Texas-based Wi-Fi Alliance, an industry group.

No major players were vying for the action here, making the area’s remoteness — which in the past slowed technological progress — the key to its advance.

Morrow County, which borders Hermiston and spans 2,000 square miles, still doesn’t have a single traffic light. It only has 11,000 people, a number that does not justify a large telecom player making a big investment, said Casey Beard, the director of emergency management for the county.

Beard was looking for a wireless provider two years ago when Ziari came knocking. The county first considered his proposal at the end of 2002 and by mid-2003, part of the cloud was up.

The desert around Hermiston also happens to be the home of one of the nation’s largest stockpiles of Cold War-era chemical weapons. Under federal guidelines, local government officials were required to devise an emergency evacuation plan for the accidental release of nerve and mustard agents.

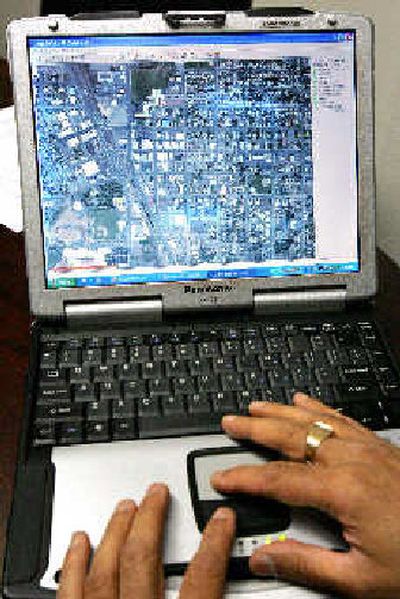

Now, emergency responders in the three counties surrounding the Umatilla Chemical Depot are equipped with laptop computers that are Wi-Fi ready. These laptops are set up to detail the size and direction of a potential chemical leak, enabling responders to direct evacuees from the field.

While the network was initially set up for the benefit of city and county officials, it’s the area’s businesses that stand to gain the most, say industry experts.

For the Columbia River Port of Umatilla, one of the largest grain ports in the nation, the wireless network is being used to set up a high-tech security perimeter that will scan bar codes on incoming cargo.

“It has opened our eyes and minds to possibilities. Now that we’re not tied to offices and wires and poles, now what can we do?” said Kim Puzey, port director.