Prosecutor’s nature well-suited to case

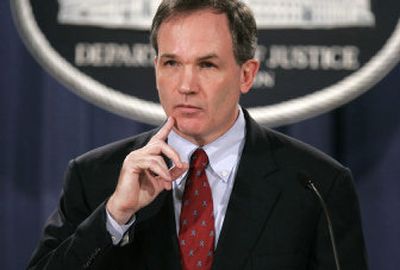

WASHINGTON – The reputation of Patrick J. Fitzgerald was well-known to colleagues, defense lawyers and others long before he brought criminal charges against I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby in the CIA leak investigation: meticulous, aggressive, intense and, most of all, by-the-book.

All those traits were on public display Friday as the special prosecutor delineated his reasons for seeking Libby’s indictment by a federal grand jury. The traits were also on display in the charges themselves.

Within hours of the grand jury’s indictments, Fitzgerald was being described by some critics as being overly cautious in limiting his charges to Libby, while others portrayed him as being overzealous and overreaching in his determination to bring any criminal case at all.

But according to some of Fitzgerald’s legal associates, friends and former adversaries, Fitzgerald did just what they expected: He filed exactly what he believed the facts called for, no more and no less.

Some former colleagues and adversaries agree that Fitzgerald, 44, may come across as overly aggressive, especially given the creative and at times unprecedented legal tactics he has used to prosecute terrorists and mobsters. More recently, Fitzgerald has been prosecuting top Chicago city officials on corruption charges as U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois.

But they predict that, if anything, Fitzgerald’s obsessive nature will work in his favor in the CIA leak case.

They describe him as being exceedingly careful and deliberate, and say he would only file charges if he is sure he is on solid legal footing and has gathered the evidence for a good – and winnable – case.

“One of the things that makes him so effective is that he is incredibly perceptive and insightful,” said David N. Kelley, who successfully prosecuted many organized crime and terrorism cases with Fitzgerald. “He will dive into the facts and let the facts take him where they lead him, (and he) is blinded by nothing.” On Friday, Fitzgerald hinted at the scope and breadth of the investigation, saying that he and his team of FBI agents and prosecutors didn’t spend two years looking to prove whether any one crime was committed. “Investigators do not set out to investigate a statute,” Fitzgerald said in a rapid-fire monotone. “They set out to gather the facts.”

Fitzgerald was appointed on Dec. 30, 2003, to investigate “the alleged unauthorized disclosure of a CIA employee’s identity.” But it is difficult to prove a violation of the federal law that prohibits disclosing the identity of an undercover agent.

So just a few weeks after getting his initial marching orders, Fitzgerald requested, and obtained, additional “authority to investigate and prosecute violations of any federal criminal laws related to the underlying alleged unauthorized disclosure, as well as federal crimes committed in the course of, and with intent to interfere with, your investigation, such as perjury, obstruction of justice, destruction of evidence, and intimidation of witnesses,” according to a memo made public last week.