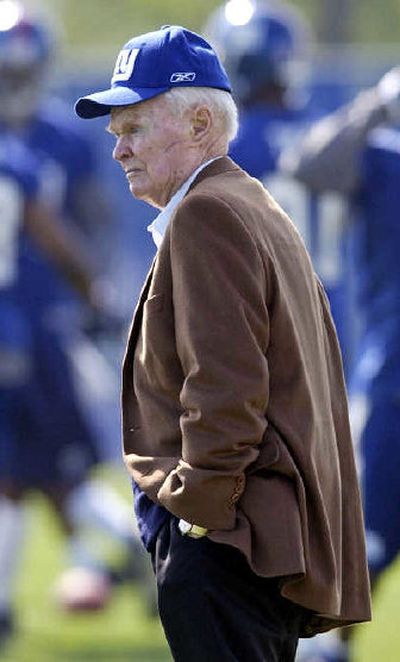

Football’s humble hero

A few years ago, after a game in Dallas, Wellington Mara had to catch a plane to an NFL owners meeting while the rest of the New York Giants flew home on their charter.

Team officials, fearing Mara would be late if he waited for the team bus, called for a car to get their owner to the airport. A stretch limo showed up.

“I’m not taking that,” Mara said.

“Go ahead, it’s here, just take it,” he was told.

“I don’t need one of those,” grumped Mara, who waited for the team and barely made his flight.

That was typical of the Giants’ longtime owner, who died Tuesday at the age of 89, the patriarch of the NFL and a man whose commitment to revenue sharing more than 40 years ago is the most important reason it is the nation’s premier sports league.

In a “look at me” era, even among owners, he put himself last. His family, his religion, his players and Giants fans were 1-2-3-4 in whatever order you’d care to put them.

“In a way, it was the Marine ethic,” said Ernie Accorsi, the Giants’ general manager. “You know the rules? It’s the officers who eat last. He would always consider himself last.”

Somewhere, Mara is probably smiling in his shy (and sly) way about all the praise heaped upon him over the last few days, especially kind words from the likes of Daniel Snyder, Jerry Jones and George Steinbrenner, whose ownership style was the antithesis of his.

Talk to anyone who met him for the first time and the reaction was always a surprised, “He’s so humble, so gentle, so friendly.”

Absolutely.

From a distance, Mara seemed on a pedestal somewhere between George Washington and Vince Lombardi. In reality, he shunned celebrity, even scorned it. It was that real smile and a wry sense of humor that made him truly unique for a man of wealth and power.

When he stood up at owners meetings, a normally raucous room would turn silent and his counsel was almost always heeded. Yet he left the room inconspicuously, while others (Jones most often) headed for the television cameras.

Twenty years ago, Mara, Art Modell, Dan Rooney, Tex Schramm and others sat with Pete Rozelle in a federal courtroom almost every day during the USFL’s lawsuit against the league.

It was a tense time. Donald Trump, another man whose persona was the antithesis of Mara’s, was trying to force a merger of the spring league and the NFL, hoping to collect billions in the process. Worse, the NFL had a long losing streak in court and its lawyers, including Paul Tagliabue, were worried.

One morning, the USFL’s witness was Howard Cosell, who had, for reasons long forgotten, turned on Rozelle. He carried on to the point that Frank Rothman, the NFL’s lead attorney, finally sat down and let him ramble about the 1969 New York Jets, Muhammad Ali, and other Cosell favorites.

At the lunch break, Mara walked up to a reporter, flashed his sly smile, and whispered: “Who’s that guy doing a parody of Howard Cosell?”

The NFL finally won by losing. The jury found it had violated antitrust law, but fined it only $1, trebled to $3. The USFL went out of business and the Giants got a huge benefit – four ex-USFL players helped them win their first Super Bowl the next year, and they traded their rights to another, Gary Zimmerman, for draft picks they turned into players who helped them win again in 1990.

Mara, of course, was delighted with the victories in court and on the field. He was a competitor and suffered for nearly two decades as the front man for a losing team, the man who sat and watched planes fly over his stadium trailing banners with messages like: “Fifteen years of lousy football … We’ve had enough.”

Mara cared about the fans then, regularly answering even the most hostile letters. And it was the fans who were in his thoughts when he made major decisions.

Two years ago, a team that hoped to challenge for a Super Bowl berth collapsed in the second half of the season. The last straw was a game against Buffalo that began with a full stadium that was three-quarters empty by the fourth quarter of a 24-7 loss.

It was then he decided to fire Jim Fassel, a coach who a few years earlier had taken the team to the Super Bowl, and only a year before had earned a hearty, though private, endorsement from the owner. “The message comes across loud and clear,” Mara said of the fan exodus. “All it tells me is that we need to improve the product.”

How many sports owners are loved by their players?

Mara was, in part because he was at practice almost every day, always congratulated them after wins and losses, and considered himself more a football man than a businessman although, unlike some, he never got involved X’s and O’s.

He was always there in a crisis.

During a period from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, an unlikely number of Giants contracted cancer: Doug Kotar, Dan Lloyd, John Tuggle, Karl Nelson and the retired Spider Lockhart. Mara made sure the team paid for their treatment, hired limousines to transport them to hospitals and pushed for studies to ensure that nothing in the ground or air near his stadium in the New Jersey Meadowlands was contributing to the statistical anomaly of cancer in young athletes.

The current player who clicked with him, surprisingly, was Jeremy Shockey, the tight end whose sometimes outrageous behavior seemed the antithesis of Mara’s strict moral code. And Shockey was one of his favorites.

While all the other players called him “Mr. Mara,” Shockey addressed him by his nickname, “Duke.”

So it wasn’t surprising that Shockey, along with running back Tiki Barber, was invited by the family to Mara’s home the day before he died to pay their last respects on behalf of the players.

Yes, Mara had a major role in making the NFL what it is. But it tells as much about the man that he also cared about Giants fans, a rare trait in these days when fans are just a vehicle for turning a buck.

He was the classiest of class acts.