Intuition may be key to success of new Fed chairman

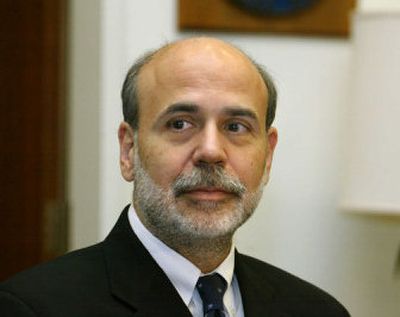

WASHINGTON – Ben Bernanke, the president’s pick to head the Federal Reserve Board, has the resume for the job, but former Fed governors and other experts say his success will depend in part on whether his intuitive skills can match Alan Greenspan’s legendary judgment.

The road Bernanke traveled to the top was paved with research at Princeton University, not with real-world business experience. No one doubts his book smarts, but some question whether he understands market psychology like his predecessors do.

Before becoming Fed chairman in 1987, Greenspan was a long-standing Manhattan-based hired gun for corporations that paid top dollar for his economic forecasts. His predecessor, Paul Volcker, ran the Fed’s New York branch.

In those roles, both future Fed chairmen rubbed shoulders daily with international finance and Wall Street moguls. That experience schooled them in how markets sometimes move more on emotion and psychology than on hard-headed economic calculation, and it informed their judgment ever after.

Bernanke’s experience, in contrast, is primarily in academia. That raises concerns about what kind of Fed chairman he’ll be. When deciding whether to raise interest rates, potentially slowing the economy and affecting Americans’ jobs, will he rely on strict mathematical models developed on university campuses? Or will he factor in intuition?

“When you’re an economist trained in conceptual stuff, you tend to be less intuitive. You fall back on this conceptual framework that the profession has invested a lot of time in,” said James Glassman, a senior policy strategist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York.

Glassman was a self-described academic economist at the Federal Reserve from 1979 to 1988. He helped Greenspan in his shift to Fed chairman. Like many at the Fed, Glassman squirmed when he realized Greenspan didn’t limit himself to strict conceptual models and favored his own personal judgment about the economy.

“I saw in Greenspan somebody who thinks differently about the world than I did. Over time, I watched this process and (realized) that’s what gave Greenspan such an edge,” Glassman said. “The real edge he had is that he’s fairly humble and realizes that no human being knows the answer, and he listens to market signals for guidance.”

Edward Gramlich was a Fed governor until August, working alongside Bernanke and Greenspan on the board. He believes well-honed intuition is essential, especially when deciding when to start or stop a cycle of rising interest rates, because their effect on the broader economy often isn’t evident for months.

“I think that Greenspan does have a very good intuitive sense of the economy, and the hardest thing with central banking is dealing with turning points,” said Gramlich, now interim provost of the University of Michigan.

But intuition isn’t everything, Gramlich said.

“Knowing how to spot turning points is partly a matter of very intense scrutiny of the data, disaggregating numbers. Alan Greenspan is extremely good at that… . He’s probably one of the world’s best at that. Ben would not be far behind.”

Greenspan believes in breaking the economy down to its smallest pieces, looking at what economists called “disaggregated” data. He doesn’t want just a statistic on, say, productivity, the output of a worker per hour, but rather productivity across every sector and subsector of the economy.

This approach led Greenspan to an important discovery in the 1990s. Then, fellow Fed governors wanted to raise interest rates to head off inflation. But Greenspan recognized that rate hikes weren’t needed because productivity was growing faster than conventional statistics showed. That meant the economy could surge without inflation, so he left interest rates low and let the ‘90s boom roll.

In short, Greenspan didn’t trust conventional economic models and relied on his intuition, which told him something was amiss in the data.

Bernanke’s academic bent contrasts with Greenspan’s blend of analysis and intuition. Bernanke favors inflation targeting – having the Fed set explicit targets for how much inflation it will tolerate, then rigidly meet the targets. That relies on complicated mathematical models. Followed strictly, it effectively puts policy-making on autopilot, minimizing judgment.

Greenspan, in his first speech since Bernanke’s nomination, advised his successor Wednesday to keep an open mind.

“Economic policy-makers face enormous uncertainty. Economic models provide a set of useful tools to frame future outcomes, but as we were reminded repeatedly during our efforts to forecast the economy in 1974 and 1975, models can go off track in myriad ways,” Greenspan said. “Objective and thorough analysis … is the most effective counterweight to this challenge.”