Ex-Taliban leaders seeking office

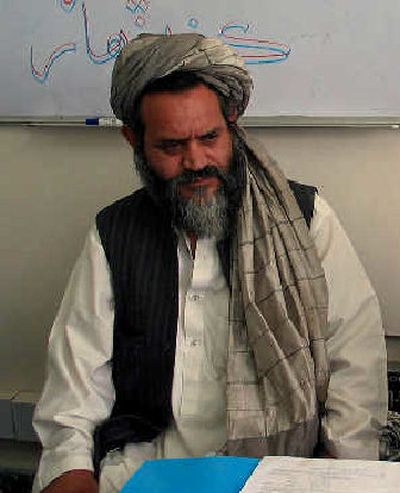

KABUL, Afghanistan – Four years ago, Mohammed Khaksar was the Taliban’s deputy interior minister, a powerful post in a regime feared for its Islamic fundamentalist policies, mistreatment of women and support for al-Qaida.

Now, he is one of at least four former senior Taliban officials running in U.S.-backed Sept. 18 elections for a new national Legislature, a vote that is seen as a key step in building Afghanistan’s democracy after a quarter century of fighting.

The Taliban candidacies come as holdouts from the Taliban regime pursue a reinvigorated insurgency that is seeking to undermine the vote. Their rebellion has caused more than 1,100 deaths in the past six months and has left large chunks of the country off-limits to aid workers.

Having publicly renounced the movement that was ousted by American-led forces in late 2001, the ex-Taliban officials running for office say it is better to pursue their goals peacefully.

“We need a strong government. We need (Islamic) Sharia law,” Khaksar told the Associated Press in an interview. “But I am no longer a member of the Taliban. I only want good things for this country.”

Still, many Afghans who suffered during the Taliban’s reign are troubled.

“These Taliban candidates were decision-makers in the regime. They were involved in policy that resulted in serious human-rights violations,” said Ahmad Nader Nadery at the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission. “I hope people will not vote for them. We have to keep them out of Parliament.”

President Hamid Karzai has encouraged Taliban members to leave the extremist group and go through a formal reconciliation program. So far, about 300 rank-and-file members and some 50 senior officials have done so.

“Those who no longer are involved in terrorism are welcome to join the peace process and take part in the elections,” said Karim Rahimi, Karzai’s spokesman.

“We need reconciliation. There were hundreds of ordinary people in the ranks of the Taliban. If we give them a chance, they will work for the future of the country rather than fighting against it,” Rahimi said.

Of the senior ex-Taliban officials seeking office, the highest-profile is Wakil Ahmad Mutawakil, the former Taliban foreign minister who spent three years in U.S. custody and then under house arrest after turning himself in. He is running as an independent candidate in the southern city of Kandahar, the Taliban’s former stronghold.

Qala Mudin, the former Taliban minister of vice and virtue, also is a candidate. Before the Taliban regime was ousted, officers from his department used to beat men for not praying frequently enough and women for not wearing the all-encompassing burqa.

Both declined requests for interviews.

Khaksar, the former deputy interior minister, said militants have tried to kill him. He secretly contacted the United States in 1999 to seek American help in stopping the Taliban, and he renounced the movement after its collapse.

“We want peace. We want security. We want good relations with the whole world,” he said. “But we also have to abide by our own customs. We need an Islamic system.”

Khaksar declined to say whether he still supports the Taliban’s strict interpretation of Islamic law, which included amputating the hands of thieves and stoning adulterers to death. The Taliban also barred girls from schools and women from jobs.

Khaksar said he favors the presence of the 21,000-strong U.S.-led coalition that is battling Taliban-led militants across southern and eastern parts of Afghanistan.

“We need the international troops to keep the peace,” he said.