Clean-air advocate quits over dust-ups

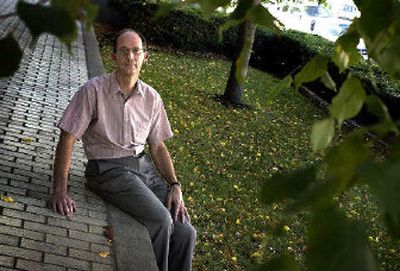

Eric Skelton, a nationally known air quality expert who helped get Spokane off the federal list of cities with the dirtiest air, has resigned as director of the Spokane County Air Pollution Control Authority.

Skelton says he’s no longer willing to work with a board he claims is hostile to him and that has put increasing pressure on him to be less assertive in regulating local business.

“I’ve simply had it,” said Skelton. His resignation letter was submitted Friday and he’ll leave his job on Sept. 30. In an e-mail to his supporters on Sunday, Skelton said he’ll continue his work in another city – “where the representatives of the public believe that preserving and improving air quality is a lofty goal worthy of their attention.”

Skelton’s departure will be a big loss for Spokane, said Dr. Kim Thorburn, director of the Spokane Regional Health District and chairwoman of the Washington State Board of Health.

“It’s too bad for our community. It’s been under Eric’s leadership that we’ve seen the turnaround in our air quality. He’s highly qualified. He was recruited here when there was a group of people committed to cleaning up the air. He just feels it’s a very different climate than when he came here,” Thorburn said.

Skelton is the victim of a smear campaign aided and abetted by SCAPCA’s board, said Karen Lindholdt, a public-interest environmental attorney. “We live in a political climate where industry feels enabled to go after someone who is cleaning up the air,” Lindholdt said.

Spokane County Commissioner Todd Mielke, who joined the SCAPCA board last fall, denied there was an intentional effort to get rid of Skelton. Recent accusations by two businessmen that SCAPCA staff had fraudulently altered asbestos inspection reports proved to be “without merit,” Mielke said. But the board wants to redirect SCAPCA from a “heavy-handed” regulatory approach used in the past, where the agency obtained some of its revenues for its $1.8 million annual budget through fines on regulated industries, Mielke said.

“The so-called ‘heavy-handed’ program we’re running was adopted by the SCAPCA board in 2002. We are carrying out what the board directed,” Skelton said.

Skelton’s departure may mark an about-face from the early 1990s, when county commissioners pushed for a more assertive board to curb carbon monoxide, dust and field smoke pollution. Spokane had repeatedly flunked air-quality standards for carbon monoxide and particulates, and tough federal sanctions on industry loomed if the county couldn’t clean up its air. Skelton, an air toxics expert in Sacramento, was the top choice in a national search in 1991.

On Aug. 30 this year, Spokane was removed from the federal government’s dirty air list, and Skelton was widely credited by state and federal clean-air officials with leading the way.

Meanwhile, tension between Skelton and the SCAPCA board has been building for months.

The board called him into a closed-door session in April, chiding him for helping the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency work on a policy memo supporting stricter emission standards on tailpipe emissions from automobiles based on stringent California limits – a change in state law under consideration at the time in the Washington Legislature.

The board acted after Chud Wendle, president of Wendle Motors Inc., an auto dealer who opposes the California standards, complained to board members about Skelton’s input, which he discovered from a public records request.

Spokane County Commissioner Phil Harris, also a SCAPCA board member, echoed Wendle’s concerns, saying the legislation will “run all of our business for larger vehicles across the state line” into Idaho. Mielke said he shared Harris’ concerns and he was “tired of seeing Spokane be the best economic development tool for Kootenai County,” according to the board minutes.

Wendle came to the April board meeting, where he laid out his complaints, Skelton said. “His message was, somebody needed to rein me in. The board took me behind closed doors and said, don’t do this again,” Skelton said.

The board said afterwards it would not take a position for or against the California emission limits under consideration in the Legislature. The Legislature later endorsed the stricter California mileage standards if Oregon concurred; Oregon’s governor recently signed an executive order supporting them.

Wendle did not respond this week to a request for comment on Skelton’s resignation.

The criticism of Skelton continued this summer – most loudly from Harris.

At SCAPCA’s June meeting, Harris remarked that Skelton did his job “only half the time.” He accused SCAPCA of being management-heavy and said if Skelton wanted more money than the $93,000 he earns as the top manager, “he should look somewhere else,” according to board minutes. An assistant to Harris said he’s out of the country this week and unavailable for comment.

Skelton said he told Harris that SCAPCA’s managers also run projects and the county “gets good payback from their managers because they are also workers.”

In August, the board scheduled a meeting to listen to complaints from two local businesses, Inland Asphalt and Northwest Renovators, Inc., that SCAPCA was meddling in zoning decisions and too quick to hand out fines and penalties. At that meeting, renovators Mike Lee and Doug Gore accused SCAPCA of falsifying asbestos tests at a burned-put property on East Sprague that they’d purchased as an investment.

Harris referred the matter to the Spokane County prosecutor for investigation of possible criminal fraud. The prosecutor turned the asbestos documents over to city police. The accusation turned out to be meritless, according to an internal review presented to the SCAPCA board in September by staff attorney Michelle Wolkey.

“It does not appear there was any intentional or unintentional falsification at SCAPCA,” Wolkey said.

Alarmed by the tone of the August meeting, Skelton’s supporters in the environmental and public health communities fought back. About 50 people attended the SCAPCA board’s September meeting, where speakers said Spokane was lucky to have Skelton and chided the board for its one-sided treatment of him.

At the meeting, Harris denied he was out to get Skelton and said the board was simply reviewing how SCAPCA does business with its “customers.”

Paul Lindholdt, an Eastern Washington University professor and environmental activist, criticized the board for its narrow focus on business interests. “We are all customers of SCAPCA,” Lindholdt said.

The board was planning another closed-door session for its October board meeting to question Skelton about his handling of yet another controversy.

The latest incident involved a letter Skelton sent last month to Anne Bailey, risk manager for Eastern Washington University who oversees asbestos issues. Her husband, Sam Bailey, is a private asbestos inspector who recently worked on a board-ordered asbestos cleanup plan for Gore and Lee at their East Sprague property.

Skelton’s letter was delivered after Bailey attended the August board meeting to comment on a new asbestos survey form SCAPCA was developing for use with private asbestos contractors working in burned-out buildings. She said the new SCAPCA procedures represented a major change that would raise costs for asbestos contractors and should go through a formal hearing and public comment process.

“I’m a department manager. My job is to keep abreast of the rules,” Bailey said this week.

On Aug. 29, Skelton wrote to Bailey, saying she had no business representing EWU at the August meeting because it was a special board meeting narrowly focused on the complaints by the private businesses and had nothing to do with the university. “I wanted to know what prompted her to come,” Skelton said.

“It was a public meeting,” Bailey said. “I wasn’t trying to make a big stink, and I wasn’t attacking SCAPCA.” Bailey said Tuesday she was sorry to learn that Skelton has resigned. “I think SCAPCA has done a lot of good for Spokane County,” she said.

This time, faced with another board inquiry, Skelton balked at being hauled to the woodshed again. “In April, I agreed because I was afraid I’d lose my job. This time, I said enough is enough,” Skelton said. A public employee has a right to have complaints handled in open public session where both sides can be heard, he said.