Wiesenthal kept focus on Nazi war criminals

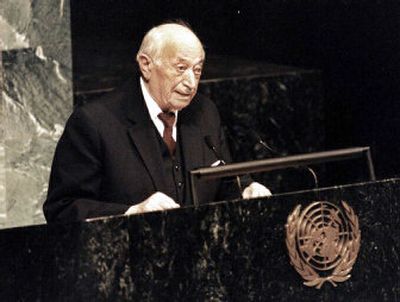

When Simon Wiesenthal died Tuesday in his sleep at age 96 in Vienna, Austria, he had outlasted almost all of the thousands of former Nazis whose dossiers he meticulously collected in his Vienna offices. But surviving them had not been Wiesenthal’s goal. Making them answer for their atrocities was.

Partly because of dogged pursuit by Wiesenthal, a survivor of the Nazi concentration camps, many did pay, including the Gestapo officer who arrested Anne Frank in her secret attic, the commandant of two death camps in Poland and, most spectacularly, Adolf Eichmann, the industrious technocrat who used his knack for solving problems to contrive the mechanics of the Nazis’ Final Solution.

Wiesenthal’s activities have been credited with drawing the world’s attention to the Holocaust when it was inclined to forget and with helping to bring hundreds of former Nazis to justice.

To many, he was known as “the Nazi hunter,” as relentless in his pursuit of his prey as the perpetrators of the Holocaust had been in theirs. But unlike the Nazis, who annihilated hope, Wiesenthal’s efforts restored a measure of faith that justice could prevail over monstrous evil.

“He not only tracked down quite a few Nazis, but he made the pursuit of Nazi war criminals something that was front and center,” Deborah Lipstadt, a Holocaust scholar at Emory University, said Tuesday. “He also made clear that this wasn’t about vengeance but about bringing murderers to justice. He was talking about it when others were not.”

Wiesenthal saw his hunt for Nazi war criminals as an admonishment that would outlive him and them. “The only value of nearly five decades of my work is a warning to the murderers of tomorrow that they will never rest,” he said in 1994.

Wiesenthal, who lost as many as 90 members of his family in the Holocaust, did not sidestep detractors or controversies. Some criticized him for suggesting that in addition to 6 million Jewish victims, the Holocaust had claimed 5 million non-Jews. His assertion was problematic in definition and arithmetic, and many thought that Wiesenthal had made the claim to stoke non-Jewish support of his efforts.

Some critics, including Nobel Prize winner Elie Wiesel, accused Wiesenthal of grandstanding, of overstating the number of Nazis he helped collar (he claimed 1,100) and his role in their capture.

Wiesenthal’s longtime friend Martin Mendelsohn, a Washington attorney who headed what is now the Office of Special Investigations in the U.S. Justice Department, said Wiesenthal had no choice but to try to attract attention if he was to spur governments to address war crimes.

“Of course, he was a self-promoter,” Mendelsohn said, “but when no one is listening, you have to be.”

Wiesenthal was born Dec. 31, 1908 in Buczacz, in what is now western Ukraine. In 1932 was awarded a degree in architectural engineering by the Technical University of Prague in Czechoslovakia. He went to work for an architectural firm in Ukraine and married Cyla Mueller in 1936.

When the Germans invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he was swept up by the SS. He was moved among several concentration camps, narrowly missed numerous mass killings, attempted suicide twice to avoid torture and endured forced marches.

When he was liberated from the Mauthausen camp by American forces on May 5, 1945, the 6-foot Wiesenthal weighed less than 100 pounds.

Reunited with his wife – each thought the other was dead – Wiesenthal offered to describe everything he had witnessed to a U.S. Army section investigating war crimes. The evidence was used in prosecutions.

That effort led to his forming the Jewish Historic Documentation Center, a group of volunteers who worked to assemble evidence for trials. But as the Cold War deepened, governments lost their appetite for prosecuting war criminals. Wiesenthal’s volunteers drifted away, his money dried up, and he closed shop in 1954.

During that period, he received credible information that Eichmann, one of his most prized targets, was in Argentina. He shared his information with the FBI and the Israelis, and the Israelis captured Eichmann in Buenos Aires. He was tried in Jerusalem and executed.

Encouraged by the success in tracking down Eichmann, Wiesenthal opened the Jewish Documentation Center in a cramped, three-room office in Vienna, where he developed tips, researched records and tracked down witnesses. That led to the prosecution of hundreds of war criminals and ignited public zeal in seeing justice done.