Iraq veterans join POW ceremony

The war veterans on one side of the aisle bore the physical scars of wounds in Iraq.

Those on the other side carried the invisible emotional scars of surviving prisoner camps in Japan, Germany, Korea and Vietnam.

But the decades and generations dividing the two groups of soldiers evaporated Friday in a ceremony honoring prisoners of war.

This was the first year that Iraq War veterans participated in the annual POW Remembrance Day ceremony at Spokane’s Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

Many were still recovering from their own war wounds but said they wanted to honor those who served before them – those who survived the horrors of World War II’s Bataan Death March and German POW camps and the Vietnam War’s “Hanoi Hilton.”

“It’s just a complete honor to be able to respect their generation, the ex-POWs,” said Army National Guard Sgt. Scott DeWaide of the 81st Brigade. His father served in World War II but was not a POW.

Washington First Gentleman Mike Gregoire was the event’s highlighted speaker.

About 100 ex-POWs and wives and widows of former POWs belong to the Spokane Chapter of American Ex-Prisoners of War, but just 10 former POWs were able to attend Friday’s ceremony.

Don Head of Spokane was captured in World War II’s Battle of the Bulge. After being herded into a rail car and taken to a POW camp near Frankfurt, Head endured four months of food deprivation, losing more than 60 pounds before being liberated.

Meals consisted of watery coffee or tea and rutabaga soup for lunch, bread for dinner – one loaf for 10 men.

“All of us have something wrong with us,” said Head, who still endures severe pain in his feet because of the frostbite he suffered more than 60 years ago.

Jack Donohoe was captured by the Japanese and survived the Bataan Death March and a prisoner camp.

“The Japanese at the end of the war weren’t satisfied with the numbers of Americans they’d killed, tortured and starved,” said Carroll McInroe, the VA Medical Center’s POW coordinator. So, said McInroe, the Japanese loaded men like Donohoe onto unmarked boats to ship them to Japan for more forced labor.

Donohoe’s boat was destroyed by an American ship whose crew was unaware it held POWs.

He was one of just 81 survivors able to swim to shore and was later rescued by Filipino guerrillas and then retrieved by an American submarine.

Elton Wood was one of the 83 crew members on the USS Pueblo, which was confronted by four North Korean torpedo boats in 1968. He spent 11 months as a POW in Pyongyang and suffered severe beatings at the hands of his captors.

Others at the ceremony were shot down over Vietnam and Germany.

As McInroe told of each POW’s ordeals, the Iraq War veterans listened, looking from time to time over at the veterans who preceded them.

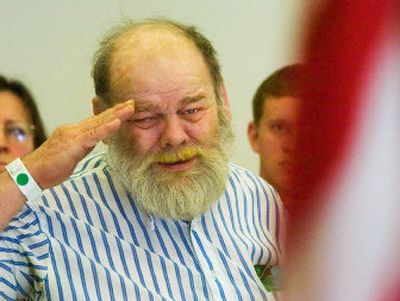

And while raised, red scars marked the healing physical wounds of some of the younger veterans, the tears shed by their older counterparts spoke of other wounds that never heal.

“Most of us say, ‘How come I’m here? How come I’m still here?’ ” Head said. “It never ends. It’s with you every day.”