Kempthorne gets earful in visit to improve conservation cooperation

Environmentalists worked with business leaders to come up with a plan to clean up the Spokane River. Schoolchildren volunteered thousands of hours to help out at the Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge. Tribes, farmers and state leaders recently found common ground on managing water in the Columbia River.

Such stories were highlighted Wednesday in Spokane during a visit by Interior Secretary Dirk Kempthorne, who was in the region to kick off a 24-city national tour the Bush Administration hopes will gather ideas on how to foster more cooperation in conservation.

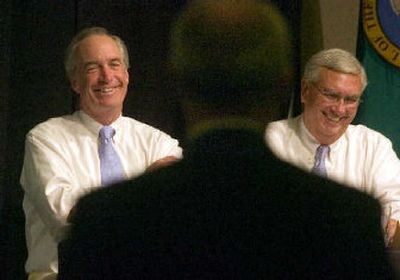

“We may not agree by the end of the day, but by golly we’re going to put in the effort to come out and listen,” said Kempthorne, whose department manages a fifth of the land in the United States. Kempthorne was joined by EPA Administrator Stephen Johnson.

The 180 or so people attending the forum at the Spokane Convention Center had much advice to give the government. More often than not, they expressed anger and frustration over federal environmental policies.

“I have a real hard time getting excited about cooperative anything,” said Joel Kretz, a state representative from Wauconda, Wash. Kretz expressed bitterness over the massive wildfires burning in north-central Washington, which he blamed on beetle-infested trees on federal land that “should’ve been harvested years ago.”

When it comes to federal environmental laws and programs, Kretz said, “It hasn’t been very cooperative; it’s been coercive.”

Protected by a squadron of Secret Service agents and wearing a pair of oxblood-colored cowboy boots, Kempthorne listened quietly to the testimony, nodding his head occasionally and dashing off winks when old friends stepped to the microphone. The former governor of Idaho is now in his second month leading the Interior Department.

For at least the first two hours of the testimony, most of the comments were critical of federal environmental programs, particularly the Endangered Species Act. Dave Billingsley, a rancher from Douglas County, Wash., said he lost access to 2,800 acres of pasture as part of a federal effort to protect the Columbia Basin pygmy rabbits, which are now believed to be extinct in the wild. Billingsley said he and his neighbors are fearful that more rabbits might show up, which could mean more restrictions would be placed on grazing or agriculture.

“When I have neighbors calling, ‘I think I have a rabbit, what should I do?’ I tell them to be quiet,” Billingsley said, adding that the federal government needs to somehow provide incentives for landowners to help conserve species, otherwise “We aren’t going to recover anything.”

The handful of environmentalists who spoke urged against gutting laws aimed at protecting wildlife, water and clean air. Such laws “create the incentive for cooperation to happen,” said Rob Masonis, with American Rivers.

In anticipation of Kempthorne’s visit, the Sierra Club issued a statement warning against placing too much faith in cooperating with the Bush administration on environmental issues. “We have found that it can often be the resources that we value so much – fisheries, healthy rivers, and wildlife habitat – that are sadly sacrificed in the name of collaboration,” it said.

Much of the testimony criticized federal management of wild salmon in the Northwest. Environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, say collaboration has failed to bring any hope for the threatened and endangered fish. Homebuilders, farmers and representatives from the timber industry say they feel the recovery process will forever hamstring their businesses.

“What is the target? What is the goal? When will these be recovered?” asked Washington state Sen. Bob Morton, R-Orient.

Before the listening session, Kempthorne said the president’s push for cooperative conservation would be a hallmark of his environmental record. When asked what else would be part of the Bush environmental legacy, Kempthorne pointed out the recent creation of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands National Monument, as well as a $4.7 billion investment in reducing the maintenance backlog at national parks.

“You’re going to see more great things accomplished,” Kempthorne promised.