League patriarch vs. likable geek

DETROIT – Dan Rooney was attending the funeral of New York Giants owner Wellington Mara last October when he felt a tap on his shoulder.

He turned around and saw Bill Parcells.

“You have to carry the torch,” the two-time Super Bowl-winning coach told the owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers. “You’re our guiding light now.”

The 73-year-old Rooney has been one of the NFL’s inner circle for a quarter-century or longer.

But the death of Mara, the Giants owner who died at 89, made Rooney the last active member of the NFL’s founding fathers. Or, more accurately, the son of a founding father: Art Rooney, known as “The Chief,” started the team in 1933 as the Pittsburgh Pirates when his son was a year old.

Paul Allen, the owner of the Seattle Seahawks, whom Rooney’s Steelers will meet in the Super Bowl next Sunday, is a founding father himself – of Microsoft, which he began in 1976 with Bill Gates.

If Rooney is the NFL’s most influential owner, Allen might be its least.

“I’ve only met him twice,” Rooney said this week. “He seems like a pretty nice guy.”

Still, the man listed by Forbes as the world’s seventh richest (Gates is No. 1) is becoming more visible lately as the Seahawks have ascended to a place in the sports world they’ve never before approached. A computer whiz who dropped out of Washington State, the 52-year-old Allen has always shunned the public spotlight. He left Microsoft in 1983 to battle Hodgkin’s disease and Gates has always been the face of the software giant.

Rooney actually cares little about attention, too.

He has no biography in the team’s media guide, where the only reference to him is under administration on page 2: “Daniel M. Rooney, Chairman.”

And while he’s far more available to the public and the media, he doesn’t seek the spotlight, often walking quietly out of league meetings.

Truth is, the shy Allen and the more open Rooney actually have a lot in common.

Both are patient with their teams.

The Steelers have had two coaches since 1969 – Bill Cowher, hired in 1992, is the longest-serving current NFL coach with the same team and has survived a few 6-10 seasons that would have cost him his job with less patient bosses.

Allen has stuck with Mike Holmgren, hired in 1999, even though entering this season his record was 50-49 with the Seahawks, including 0-3 in the postseason, after winning one Super Bowl and getting to another in Green Bay.

Both are civic-minded.

Rooney is a fixture in Pittsburgh going back to 1949, when he was a second-team all-city quarterback behind a guy named John Unitas. And his interests are almost all in sports – he and his brothers own racetracks and dog tracks, businesses started by their father.

Allen, who also owns the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers, bought the Seahawks in 1997 to keep former owner Ken Behring from moving them to his home state of California.

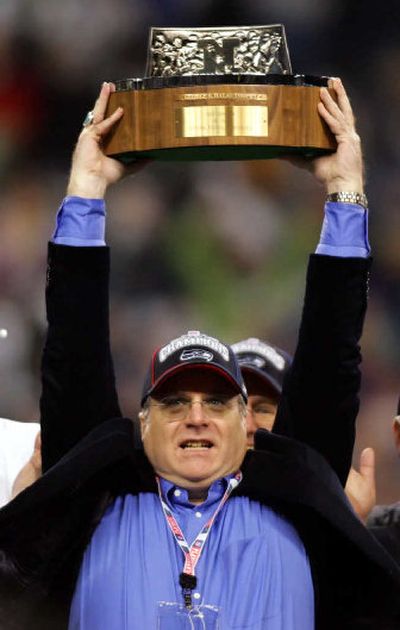

The Seahawks’ success has brought Allen out in public more often. “Reclusive” is being dropped as the prefix to “billionaire.” He’s been surfacing a lot lately to cheer on his team, raising the “12th Man” banner that honors the Qwest Field fans before the NFC championship game, and showing up to chat with the media in the locker room.

“I’ve been to a few Super Bowls and I was at the game last year just hoping that one day we’d be able to get there,” he said. “I may seem like a mild-mannered guy, but my gut was churning inside: ‘Let’s win this game. Just win this game. We’ve got to win this game.’ “

Spoken like the fan he has always been.

“If you’re a fan of NFL football, how great is it to be able to root on your team to win the Super Bowl? It’s incredible.”

Rooney has had a lot more football success – and a lot more failure.

But he’s handled both with a sense of perspective, one reason why NFL commissioners past and present turn to him as the voice of reason.

He helped end player strikes in 1982 and 1987. More recently, he chaired the league committee that has helped increase the number of black coaches in the past four years from two to six – “the Rooney Rule” requires all teams with head coaching vacancies to interview at least one minority candidate.

He also is one of the people who worked out the modern salary cap, and is involved in a revenue-sharing dispute among owners as the leader of a number of small-market teams.

Rooney’s commitment to diversity is shared by Allen, who now directs Vulcan, Inc., a management company which invests in science, the arts and movie production, among other things. The six-person Seahawks board of directors includes a black, an Asian and a woman, Jody Patton, who also is CEO of Vulcan.

When the Seahawks and Steelers meet next Sunday in Detroit, Allen will watch the game with a fan’s eye.

Rooney will watch it as a football man, hoping things go right, but knowing they can go wrong very quickly. He’s seen both sides.

With Chuck Noll as coach, the Steelers began a run in 1974 of four Super Bowl victories in six seasons. Noll retired and Cowher came in, but the front office was shaken up a few times, even to the point that Dan Rooney fired his brother, Art Jr.

The Steelers have made the AFC championship game six times in 12 years, but won it only twice in that time.

For Rooney, that was almost as big as the first one, 31 years ago.

“I feel almost the same now as I felt then, like it’s the start of something with all the good, young players we have,” he said. “But I’ve been around this business too long to take anything for granted.”