Tough race, GOP problems keeping incumbent focused

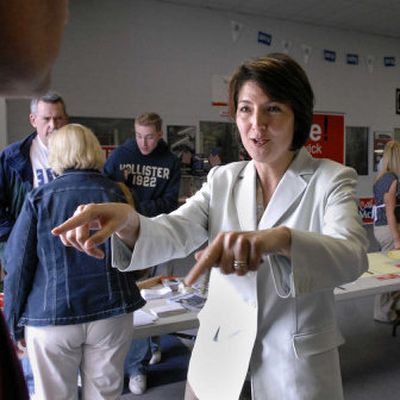

Surrounded by veterans with various campaign hats, medals and patches, Cathy McMorris tried a full-frontal assault last week on her opponent’s campaign ad that accuses her

of caring so little about veterans that “guys are dying in the parking lot” of the Spokane Veterans Affairs hospital.

Two hours earlier she’d been in front of a group of National Rifle Association supporters, urging about 60 people to do everything possible to get their friends and neighbors to vote.

“This is a tough election,” she warned. “The Democrats are organized, they’re motivated, they’re working hard.”

Three hours earlier, she’d been in Pullman, part of a “rally the troops tour” through Eastern Washington with Republican Senate candidate Mike McGavick.

Although candidates always urge supporters to be active and vigilant as an election approaches, the determined and frenetic pace underscores a surprise reality for the freshman Republican congresswoman. She’s in the toughest, and likely the closest, race of her life.

“People always say your first re-election is the hardest,” she said after one of her campaign events. While she instinctively knew that, “I probably didn’t believe it to this degree.”

That she’d have to defend her work on veterans’ services – the latest commercial by the opposition features a 25-year-old Iraq war veteran looking right into the camera and accusing her of being callous to their needs – never occurred to her.

She had worked with Sen. Patty Murray, a Democrat, to fight off closure of the Walla Walla VA hospital. “If anything, I feel it’s one of my strengths.”

Last spring, 2006 seemed to be just another easy election for 37-year-old McMorris. Sure, Democrats would complain about some votes or bills, but Spokane’s biggest employer, Fairchild Air Force Base, was spared from closure and the economy was rebounding.

Her lone Democratic opponent, Peter Goldmark, was a relative unknown with little money. She traveled Eastern Washington’s 5th District to announce her re-election bid with an upbeat video that showed her walking, talking and smiling with a variety of people.

The orchardist’s daughter with the girl-next-door smile was getting married and when possible, she introduced her fiancé, Brian Rodgers, a Spokane native and former Navy pilot she’d met last year, as the best thing that happened in her first term. She was more likely to be asked “When’s the wedding?” than “Why did you vote on …”

They married in August, during a break from campaigning and summer congressional stops around Eastern Washington. With campaign signs and literature already printed, she put off a decision on whether to go by McMorris or Rodgers until after the election.

She said she got an inkling of a tough race ahead sometime in July: “It was the day I heard Goldmark had bought 500 4-foot by 8-foot signs.”

The conventional wisdom through the summer, though, was this was an easy race. The National Republican Campaign Committee, whose job it is to keep the GOP in control of the House, didn’t set aside any money for her. Only in the last week has the NRCC taken the step of signaling its big-money donors that McMorris was in a race that needed financial support.

“That’s been my biggest challenge. Everywhere I went I’d see people and ask them for money or to get involved and they’d say ‘Cathy, you’re a shoo-in.’ “

Although she’s raised nearly $1.5 million for the campaign – $655,000 from PACs and $830,000 from individuals – there were periods when Goldmark raised more money than she did.

McMorris has faced voters every two years since 1994, when she was appointed to fill the 7th Legislative District House seat her former boss Bob Morton vacated to go to the state Senate. The first election for the daughter of a one-time Stevens County GOP chairman coincided with a Republican tidal wave in the nation, and the state, that gave the GOP rare control of both houses of the Legislature.

Lynn Harsh, chief executive officer of the conservative Evergreen Freedom Foundation, watched McMorris grow from a legislative staffer into the state House minority leader. For the first five or six years McMorris spent in Olympia, she lived in Harsh’s basement.

“She’s matured in her thinking and her ideas, how she collects information and how she uses it,” Harsh said. “She asks good questions and genuinely wants answers – I rarely see her jump to conclusions.”

McMorris’ succeeding races were relatively easy, including an unopposed run in 1998 and a 3-to-1 margin victory in 2002 over a perennial gadfly candidate. Her closest race was in 2004, when she received 60 percent of the vote against Democrat Don Barbieri for the open U.S. House seat.

But all of those elections were in years when it was good to be a Republican, at least in Eastern Washington where most legislative seats outside of the Spokane city core and most county courthouses have been held by the GOP since 1994.

This does not appear to be such a good year for Republicans in Congress nationally, but there’s no telling yet whether Washington state will be the bellwether of national disgust in 2006 that it was in 1994 or 1980 when powerful incumbent Democrats were felled.

“There’s a lot of Republicans in trouble,” agreed Duane Sommers, a former legislator who served with McMorris and later served as Spokane County assessor. “But I don’t think that the Democrats are as united as (Republicans were) in 1994.”

GOP candidates will have to sharpen their message this year, Harsh said. “Many people are disappointed with the Republicans’ apparent lack of direction.”

But friends and colleagues say McMorris’ direction as a fiscal and social conservative has always been clear and hasn’t been changed by two years in Washington, D.C.

“I think her core principles are still the same, which takes a lot when you’re a freshman back there,” said state Rep. Lynn Schindler, a Spokane Valley Republican who was McMorris’ roommate for about six years in Olympia. “She’s one of these people who really listens to her constituents. She’s willing to talk to anybody, even if they disagree with her.”

Harsh said they “disagree almost entirely” on trade issues, yet McMorris called her earlier in the year to discuss the Central America Free Trade Agreement. “She never once talked about, is that good for re-election. That may be dangerous, but it’s also noble.”

As a freshman congresswoman, McMorris’ ties to leadership scandals may be more tenuous than someone with more time in Washington, D.C. She’s the freshman Republican on the Steering Committee, which assigns each member to his or her committees, and an “assistant whip,” which is a minor leadership position.

Some years, those would be signs of an up-and-comer among the new class in Congress. This year her opponent can point out a whip is someone in charge of lining up votes for the leadership’s key issues.

“I really don’t see myself in leadership,” she said. Those two positions – assistant whip and Steering Committee member – are about getting to know other members of the House, she added, and “being effective in Congress is largely about building relationships.”

She continues to talk of unhappiness with the partisan rancor in Congress, a complaint she’s had since her first months in Washington, D.C. But now Goldmark counters that McMorris votes more than 95 percent of the time with Republicans.

Like most fledgling candidates, McMorris took money in 2004 from political action committees set up by Republican House leaders. When Duke Cunningham of California and Bob Ney of Ohio were convicted of misdeeds, she gave amounts equal to their contributions to local charities. She has so far refused to do something similar with money from Rep. Tom DeLay of Texas, who resigned but has not yet been convicted of any crime.

She’s taken less from leadership PACs this year. She has no legislative ties to former Rep. Mark Foley of Florida and took no campaign money from the now-disgraced ex-congressman whose sexually explicit messages to House pages touched off the biggest firestorm for Republican leaders. But she did receive $10,000 in 2004 from House Speaker Dennis Hastert’s Keep Our Majority PAC.

She’s resisted joining calls for Hastert to resign for his handling of information about Foley, saying she wants to wait for the results of an FBI investigation before reaching a conclusion.

McMorris outpolled Goldmark in every county in the Sept. 19 primary except Okanogan, his home county. But for the first time, state primary voters had to stick with one party’s candidates so there was no chance for crossover votes and little incentive for independents to cast ballots. Republicans and Democrats alike agreed there was no way to use those results to forecast the general election.

Then the Foley scandal broke, and the prospect of a Democratic takeover of at least one house of Congress went from casual speculation to a daily theme in the national news media. Robin Ball, a former Spokane County GOP chairwoman, said she doesn’t think people link McMorris personally to the congressional scandals in Washington, D.C.

“The ads have been so negative,” Ball said. “But I think Cathy is solid and I think people who know her, know that.”

Now the Goldmark campaign has an ad featuring Ian Anderson, a 25-year-old Iraq War veteran, who looks into the camera and explains how he was wounded and returned home, unable to work and dependent on the VA for his medical care.

Anderson then says that McMorris cut VA benefits and “guys are dying in the VA parking lot here in Spokane.” The former is an ongoing bone of contention between McMorris and Goldmark. She points out she voted for an increase in VA funding that amounted to $12 billion over two years. He counters that the number of veterans and the cost of health care is rising, and services at some VA centers are being cut back; she should have voted for more money, which was contained in a failed Democratic amendment, he contends.

The parking lot reference stems from the case of 83-year-old Clinton Fuller, who arrived at the hospital with breathing problems shortly after the urgent care center had closed. Instead of treating him there, the VA staff called an ambulance, which took Fuller to Deaconess Medical Center where he died.

The McMorris campaign’s first response to the ad was to say it was wrong because there was only one case, so there weren’t “guys,” and to point out Fuller died at Deaconess, not in the VA parking lot. That was technically correct but may have been politically tone deaf.

On Friday, McMorris mustered a roomful of veterans and military families including her husband, who served in the Navy for 22 years, then stood in front of an American flag and let them tell about her work with local service members and veterans. Combat pay is up, noted Michelle Busick, an Air Force wife.

“We’ve all had personal frustrations with the VA, but Cathy has worked to solve these frustrations,” said Jon Castle, a veteran.

McMorris also said that there are problems with the way the VA communicates with some veterans about the services and benefits it provides. Her office has helped about 125 veterans with benefit or medical care issues, but “a vet shouldn’t have to come to a congressional office to get VA benefits. There’s room for improvement.”

The Spokane VA hasn’t had an emergency room for decades, and some veterans have had problems getting reimbursed for emergency room care at local hospitals, she said later. The change in the urgent care center’s hours wasn’t well known. Her office was working on those problems even before Fuller died.

She was momentarily taken aback by an unfriendly question from a Democrat who had crashed the rally, regarding why she voted against funding for studies at the National Institutes of Health on head trauma and prosthesis problems. But she recovered to say that the vote was really about giving the NIH more ability to decide how it would spend its money, not tie it to specific programs dictated by Congress.

In an interview after the veterans rally, McMorris tried to be philosophical about the upside of a tough race.

“In the long run, it makes you work harder and think harder about what you’ve done, and what you want to accomplish,” she said.

As someone who’s been in political office most of her adult life, McMorris said she hasn’t given serious thought to what she’d do if she loses on Nov. 7, other than having a longer “honeymoon part two” before looking for a job. She has a bachelor’s degree from Pensacola Christian College and later earned an MBA at the University of Washington.

But Jennifer Dunn, a former member of the House, gave her some advice when she got to Washington, D.C. “Jennifer told me I must remember there is life after Congress.”