‘The Devil’ blends history and culture

They call Chicago the Second City.

But in 1893, the biggest city in the Midwest stood second to no American metropolis. Thanks to architect Daniel Burnham, who was given the job of preparing the city for the 1893 World’s Fair, a rough section of Chicago was transformed into something known as the “White City.”

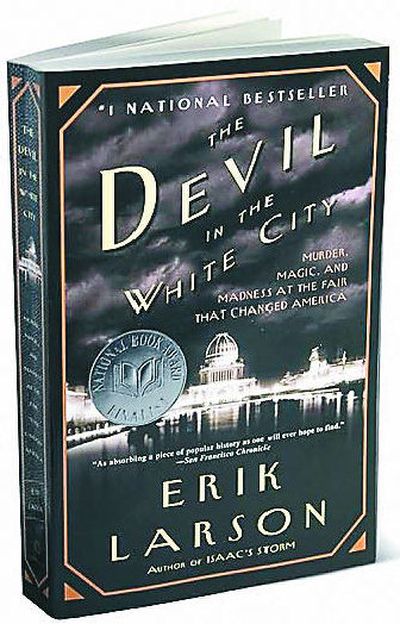

The fact that someone with a black soul ended up haunting the fairgrounds provides the basis for Seattle author Erik Larson’s nonfiction book “The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America” (Vintage, 447 pages, $14.95).

Larson’s book, a favorite of book groups across the nation, is the February choice of The Spokesman-Review Book Club.

Some readers will recognize Larson’s name. His 1999 book “Isaac’s Storm” (Vintage, 336 pages, $14 paper) was nominated for a National Book Award, was named to several Top 10 lists and earned both Book Sense of the Year and Pacific Northwest Booksellers awards.

“Devil in the White City” ended up being no less popular.

Not only does Larson use the book to explain the significance of the 1893 World’s Fair – it attracted such luminaries as Thomas Edison and Buffalo Bill, was the site of the world’s first Ferris wheel and represented the triumph of man’s ingenuity – but he proves to be an adept biographer of both Burnham and H.H. Holmes, the man who would become America’s answer to Jack the Ripper.

“Taken together, the stories of how Daniel Burnham built the fair and how Dr. Holmes used it for murder formed an entirety that was far greater than the story of either man alone would have been,” Larson said on the Random House Web site (www.randomhouse.com).

“… The juxtaposition of the architect and the murderer seemed to open a window on the forces shaping the American soul at the dawn of the 20th century.”

Burnham was a man who, early on, seemed ill-equipped for success. It was only after discovering his skills as a draftsman, then teaming up with John Wellborn Root, that Burnham helped build a firm that would be responsible for some of the tallest buildings in early Chicago history.

One of those buildings – The Montauk – had the distinction of being called the world’s first “skyscraper.”

Burhnam and Root were hired as the lead designers of the fair, putting them on the same level as the likes of Frederick Law Olmsted, the man who created New York City’s Central Park.

Holmes, to the contrary, was a twisted personality who used an inherent intelligence to, first, amass a small fortune through fraud and, second, to lure what turned out to be dozens (estimates range from 27 to 200) people to their deaths.

As he said in his 1896 confession, “I was born with the devil in me. I could not help the fact that I was a murderer, no more than the poet can help the inspiration to sing.”

The irony was that Holmes’ one-man crime wave was so easy to commit. Part of that was because of the sheer size and mass that Chicago had become.

As Larson wrote: “Anonymous death came early and often. Each of the thousand trains that entered and left the city did so at grade level. You could step from a curb and be killed by the Chicago Limited. …

“In the first six months of 1892 the city experienced nearly eight hundred homicides. Four a day. Most were prosaic, arising from robbery, argument, or sexual jealousy. Men shot women, women shot men, and children shot each other by accident.”

This, then, was life as Chicagoans experienced it in the 1890s. But what Holmes did was something new, though it seemed to come as part of new attitudes and tolerances.

“Everywhere one looked the boundary between the moral and the wicked seemed to be degrading,” Larson wrote. “Elizabeth Cady Stanton argued in favor of divorce. Clarence Darrow advocated free love. A young woman named Borden killed her parents. …

“And in Chicago, a handsome doctor stepped from a train, his surgical valise in hand. He entered a world of clamour, smoke, and steam, refulgent with the scents of murdered cattle and pigs. He found it to his liking.”

The New York Times described “The Devil in the White City” as “a dynamic, enveloping book” that “relentlessly fuses history and entertainment to give this nonfiction book the dramatic effect of a novel.”

The Chicago Sun-Times was even more specific in its praise of this “wonderfully unexpected book.”

“Larson is a historian,” the Sun-Times reviewer said, “with a novelist’s soul.”

The irony, of course, was that this kind of evil could flower in an environment of creative invention. Such a melding of good and bad was, in the end, anything but second-rate.