Gehrig’s speech still resonates

“Today … I consider myself … the luckiest man … on the face of the Earth.”

Lou Gehrig, Yankee Stadium, July 4, 1939.

Do the words echo in your ears, as they did 68 years ago today?

They do for Vinnie Anella. Not because of the clips he’s seen on TV, the credit card commercial from a few years ago, or even the movie biography of Gehrig’s life, “The Pride of the Yankees,” starring Gary Cooper in an uncanny likeness.

They still resonate in Anella’s ears because he was there.

Anella was 7, and he is likely one of the dwindling number of people still alive from the more than 62,000 who shoe-horned into Yankee Stadium that day to hear perhaps the most famous non-political speech in American history.

“I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for. Thank you.”

With those final words from Gehrig, Yankee Stadium erupted in a two-minute standing ovation. Gehrig’s No. 4 became the first uniform number retired in baseball history. Later that same year, baseball waived its five-year mandatory wait and inducted the 36-year-old Gehrig into its Hall of Fame.

“In just two sentences, Gehrig said so much. He summed it all up,” said Anella, who is retired and living in Viera, Fla., two weeks shy of his 75th birthday.

Actually, only four sentences survived from all the audio clips and movie reels that recorded Gehrig’s moving, 279-word speech.

And it was powerfully poignant and moving. Toward the end of his speech, chroniclers of the event reported that the only sound heard from the stands were people weeping.

There is Abraham Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address.” Franklin D. Roosevelt insisting, “The only thing we have to fear, is fear itself.” John F. Kennedy imploring, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.” Martin Luther King Jr.’s passionate, “I have a dream.”

And then there is Lou Gehrig, approaching death’s door, saying, “Today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth.”

It still sends chills.

That day, Gehrig’s echoing words bounced off the cathedral of old Yankee Stadium, as if to emphasize his character. And the silence, an absolute stillness enveloped everyone as Gehrig spoke into the microphone.

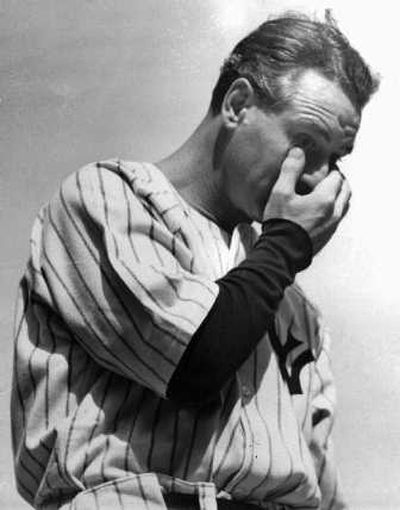

The only way Anella sees it all now is when he closes his eyes and his mind takes him back. He can still see Gehrig, withered by the disease that would come to bear his name. He was standing frail on the field during a doubleheader intermission, a man less than two years away from a death that came exactly 16 years to the day that he replaced Wally Pipp in the Yankees’ lineup. Anella can still feel the stadium’s stillness. He can still hear the echoing words.

“I was only 7, but it made an impact,” he said. “You know what I think of, though, when I see a clip of it on TV? I think of my father. We shared so many baseball games and special moments.”

Anella’s father, Joseph, was a postal worker who started work at 5 a.m. and then often took his son to afternoon games with tickets he’d get through a friend.

“Our seats were right behind the Yankees’ dugout, about five, six rows,” Anella said. “They were beautiful seats.”

As they were sitting there that day, so close, watching the famous ceremony, Anella recalls a figure emerging from the Yankees’ dugout, and his dad’s subsequent excitement.

“It’s Babe Ruth.” the father told the boy. “Look, they’re going to make up.”

Sure enough, Ruth threw his arms across Gehrig’s shoulders and hugged him about the neck as photographers snapped away. It was the first time in five years the two men spoke.

Growing up in Brooklyn and attending school two blocks from Ebbets Field, Anella experienced a lot of baseball. He recalls jockeying for position on the other side of the outfield fence at Ebbets Field on April 15, 1947, trying to get a glimpse of the action in Jackie Robinson’s historic first major-league game.

He also saw two games at Yankee Stadium during Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in 1941. After one game, his father told him to hop the wall and run onto the field. Anella, just 9, did, and he slapped DiMaggio on the back as the Yankees legend ran off the field.

“I remember two things, very distinctly,” he said. “The back of DiMaggio’s neck was so red, so sunburned. I’ll never forget the way it looked. And when I slapped him on the back, he was soaking wet.”

Two years later, while in Greenwood Lake, N.J., in the summer of 1943, Anella and his father met Babe Ruth at a gas station.

“He was larger than life, such a big guy, robust. He grabbed me and shook my hand. It happened so fast. You didn’t even think about an autograph back then.”

It was five years later, on July 26, 1948, when Ruth succumbed to cancer. For two days his body lay in state at Yankee Stadium. Anella’s father asked his son if he wanted to go and see Ruth, one last time.

“I was in high school then, and thought I was too old for that,” Anella recalled.

Some 200,000 people filed past Ruth’s casket, but Vinnie Anella wasn’t one of them.

“At the time, I didn’t really understand the historical significance.”

But now he does. Like Lou Gehrig’s famous farewell speech, he understands better.

He knows to have been at Yankee Stadium exactly 68 years ago is significant. And special. Other than his father, who has been dead 20 years, Anella has never met anyone else who was at that game. Likely, there aren’t too many people remaining.

But the words, Lou Gehrig’s immortal words, still live today.