Hospitals sale a done deal? Not yet

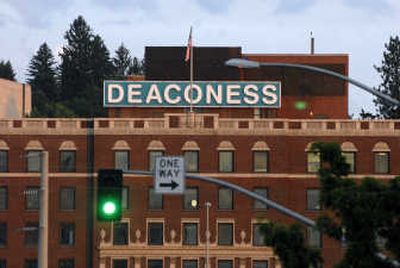

After nearly four years of roller-coaster dips and swells, Empire Health Services’ wild ride to financial stability appeared to level off this month with news that a potential buyer has been found for the century-old system that includes two Spokane hospitals.

But neither critics nor supporters of a possible sale to Community Health Systems Inc. of Tennessee should count the arrangement as a done deal, say state regulators responsible for approving it.

The proposal – signaled by a nonbinding agreement signed June 14 – marks only the second time in Washington history that a nonprofit hospital system would be sold to a for-profit buyer. The first, in Yakima in 2003, was a ground-breaking test of the state’s hospital conversion law enacted a decade ago.

Although the process is increasingly common in other parts of the country, it’s an anomaly in Washington, where seven of 97 hospitals are run by for-profit corporations.

Scrutiny of the shift, which is analyzed by the state Attorney General’s Office and approved by the state Department of Health, could take six months or more after a formal application is received, officials said.

As they did in Yakima, regulators will fix a critical gaze on everything from the proposed price tag to the promises swapped between an eager buyer and a willing seller, said Janis Sigman, manager of the health department’s facility certification program.

“It is not a rubber stamp,” she said. “We will thoroughly evaluate the application.”

At the heart of the analysis will be whether the deal properly benefits the party with the biggest stake in the decision: the public. As the statute notes, it’s the state’s job to safeguard the charitable assets of entities formed as nonprofit corporations.

For more than a century, the system that began with Deaconess Hospital has received the economic and civic benefits allotted a nonprofit company. Making sure the community is properly compensated for that investment is key, said Laurie Sobel, a lawyer with the Consumers Union, a public advocacy group.

“A nonprofit hospital system is a charitable entity. It is owned by the public,” said Sobel. “The value of the nonprofit should be considered, not just by the bricks and mortar, but by what’s the good will in the community.”

Community members with a stake in the outcome should pay attention, said Sobel. By any measure, that includes almost everyone with an interest in health care in Eastern Washington – and beyond.

With 511 beds and 2,400 employees, Empire treats more than 225,000 patients a year, snagging nearly 30 percent of the medical market in a region dominated by Providence Health System, the parent organization of Sacred Heart Medical Center, state figures show.

A potential sale could rock the foundation of that care, raising questions about everything from the status of employee union contracts and the level of charity care to the future of collaborative community endeavors such as Inland Northwest Health Services.

At the very least, state law requires that proceeds from the sale be used to create an independent charitable foundation with a mission to continue regional health care services founded on the nonprofit entity’s original values. In Yakima, Providence Health System’s sale of two hospitals to Health Management Associates Inc. meant an initial investment of $5.4 million net sale proceeds, plus an agreement by HMA to contribute $1 million a year for 10 years to the community foundation.

Nationwide, nearly 190 foundations with a combined $21.5 billion in assets have been formed or enhanced by health care conversions since the 1980s, according to Grantmakers in Health, a nonprofit agency that tracks the process.

That kind of charitable resource doesn’t come along every day, said Sobel, whose agency offers consumers advice about monitoring health care.

“Is it too early to become involved? No, definitely not,” she said. “The community should be involved from the beginning.”

The conversion process, and the required certificate of need evaluation that accompanies it, provides ample opportunity for community input in the form of public hearings and requests for comment. However, it’s up to interested parties to participate, Sobel noted.

In the case of the Empire deal, the process hasn’t begun quite yet. The letter signed in June was simply an agreement by the two entities to consider a sale, Empire and Community Health officials said.

The intent-to-sell notice represented the end of a long process spurred by Empire’s $36 million loss posted in 2004 and ensuing $40 million turnaround that led the organization to barely break even nearly two years later. Hospital officials hired Cain Bros., a Wall Street brokerage firm, last fall, hoping to seek investors or a potential buyer for the resuscitated hospital system.

More than 40 prospects were contacted by Cain Bros., said Becky Swanson, an Empire spokeswoman. Ten firms pitched formal offers; four finalists were considered. Of those, Community Health Systems, the nation’s largest for-profit hospital chain, emerged as the top contender.

Community Health recently struck a $6.8 billion deal to buy Triad Hospitals Inc., a move expected to be approved this summer, forming a megachain of 133 hospitals in 28 states with debts exceeding $9 billion.

Ron McKay, chairman of Empire’s board of directors, estimated that it would be a matter of weeks before a final agreement was inked in Spokane. But Rosemary Plorin, a spokeswoman for Community Health and veteran of many similar deals, said final agreements typically take months.

Price, of course, will be a sticking point in any potential sale – and in the final approval for any potential conversion. Neither Empire nor Community Health officials would name a figure.

Bystanders might be tempted to speculate based on Empire’s so-called “book value,” the estimated value of its physical assets, which is about $200 million, records show. But that number likely will have little relation to a final figure, said Jim Greenleaf, president of Greenleaf Valuation Group Inc. of Seattle, the independent firm that put a price on the Yakima sale. Typically, the sale price is less than book value.

“When somebody buys the asset, the book value is what goes onto their new books,” Greenleaf said. “The difference between the book value and the purchase price is generally termed ‘good will.’”

It was up to Greenleaf, for instance, to evaluate the validity of the $65 million to $75 million figure that a brokerage firm estimated for the Yakima sale. In the end, HMA offered $80 million for the two hospitals.

Figuring a fair market value is a crucial – and difficult – step in any sale, said Greenleaf, who declined to offer an estimate for the Empire sale.

“It’s not something that you’re going to do on the back of a napkin,” he said. “In the Yakima sale, there were 5,000 pages of documentation from the hospital alone.”

Still, a review of recent sales of hospitals and systems about the size of Empire provides at least a ballpark range of potential prices. Of 20 hospitals with 400 to 600 beds sold since 2000, the average price was $151.5 million, ranging from a low of $81.5 million to a high of $290 million. The figures come from data compiled by Irving Levin Associates Inc., a Connecticut publishing firm.

Terms of sales can vary, with some buyers agreeing to acquire significant debt or invest in improvements. In May, for instance, as it was negotiating the Triad deal, Community Health also completed a deal in Indiana, agreeing to pay $80 million in cash and assume $40 million in debt to acquire Porter Health, a two-hospital system with 338 beds at two sites.

In Empire’s case, the system owes about $75 million in bonded debt to the state, according to records from the Washington Health Care Facilities Authority. Jeff Nelson, chief executive officer, also had said the system will require about $100 million in infrastructure investments.

Scrutiny of the process will become easier once formal applications are filed. Details such as price, debt and other terms of sale must be included in the documents, which will be available to the public, noted Sigman, of the state Department of Health. However, there’s still a question about how accessible the documents will be. Sigman said she’d be happy to provide CDs of the application to interested people, but limited staffing would prevent her from posting information on a Web site.

That surprised Sobel, who said Spokane-area consumers should expect to be able to follow the sale of their hospital system. Even the mammoth proposed conversion of Premera Blue Cross from a nonprofit to for-profit insurance company was available online, said Sandi Peck, spokeswoman for the Washington Office of the Insurance Commissioner.

“We just had a policy decision right up front that anything that was a public document would be posted,” said Peck. Premera’s plan ultimately was rejected.

Public interest in the process may take a while to catch on, although certain segments of the community have been watching already. Changes in Empire’s operation can’t help but alter the foundation of care in the region, said Dr. Brian Seppi, president of the Spokane County Medical Society, which includes about 800 doctors.

“I think there’s hopeful anticipation that it’s going to be a smooth process and that it will go through,” Seppi said. “But the people that are using Deaconess the most understand that it’s not a done deal. They understand that there are a lot of hurdles to overcome.”