Firms hope ink sells

NEW YORK – What does Angelina Jolie have in common with Joseph Stalin and Thomas Edison as well as two out of every five Americans between the ages of 26 and 40?

They all have tattoos.

Once seen as a silent cry of rebellion, tattoos possess a status so firmly mainstream that advertisers are using them to market everything from tires and shoes to wine and energy drinks. That has its downside, though. The more acceptable tattoos become, the more they lose their edginess – and their value as advertising.

“There is always an element of rebellion or rite of passage with these things,” said David Crockett, assistant professor of marketing at the University of South Carolina. “What makes them interesting is how the marketplace appropriates that rebelliousness and serves that back to you in the form of an energy drink.”

The 7-Eleven convenience store chain recently started selling an energy drink called Inked, aimed at people who either have tattoos or those who want to think of themselves as the tattoo type. The company plans to market the drink at motorcycle rallies and tattoo conventions.

“We wanted to create a drink that appealed to men and women, and the tattoo culture has really become popular with both genders,” said 7-Eleven’s manager of noncarbonated beverages, Michele Little. “The rite of tattoo passage isn’t only limited to the young but also to those who think and act young.”

As the attention of young consumers gets spread between TV, blogs, online video and other distractions, marketers have resorted to alternative methods to get their interest.

Marketers use tattoos both as a cultural icon and as the method to deliver the message, said Kevin Lane Keller, a marketing professor at the Tuck business school at Dartmouth College.

“It’s an attempt to do something different in a fresh way,” he said.

On a never-ending quest to appeal to the young and young-minded, companies from Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. to Volvo are using tattoos in advertising and promotion. Even wine sellers have adopted the tattoo, with managers of the popular Yellow Tail brand sending 600,000 temporary tattoos out with an October issue of the New Yorker magazine and wine importer Billington Wines taking the name Big Tattoo Wines for its $10 a bottle brand.

For three years, Goodyear’s Dunlop tire unit has offered a set of free tires to anyone who will get the company’s flying-D logo tattooed somewhere on their body, and 98 people have taken up the offer. Some of them are brand loyalists who already own Dunlop tires, while others were tattoo fans who wanted to add to their body art, Dunlop brand marketing manager Janice Consolacion said. One returned for his third Dunlop tattoo this year.

For those friendly to the idea of being a walking billboard, the Web site Leaseyourbody.com connects advertisers with people who want to be paid for sporting tattoo advertisements.

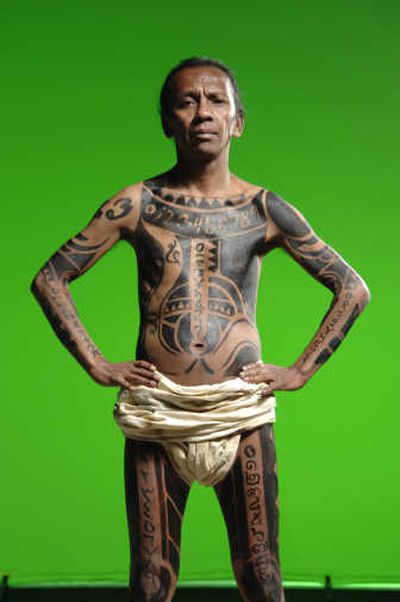

Volvo recently utilized tattoos in another way, by creating a fictional character whose tattoos spelled out the coordinates of an undersea location of $50,000 in gold coins and the keys to a new car. Linda Gangeri, national advertising manager of Volvo Cars of North America, said the tattoo man was a way to get people to think differently about the Volvo brand.

Tattoos are becoming so pervasive that some see them as less effective in marketing to trendsetters.

Nathan Lin, a tattoo artist and organizer of the annual Boston Tattoo Convention, said the event’s sponsors reflect the shifting demographics of tattoo culture in the U.S. This year, it was Toyota Motor Corp.’s Scion brand and Anheuser Busch Cos.’ Budweiser. Next year’s convention has gotten sponsorship interest from Internet service provider NetZero among other corporate names, he said.

“It puts it far outside the stereotypes of bikers and rough types,” Lin said. “People think of urban moms having tattoos.”

A study done last year by the Pew Research Center shows that 36 percent of 18- to 25-year-olds have at least one tattoo, while an even higher 40 percent of 26- to 40-year-olds have at least one.

Once corporations use tattoos, it’s clear they have lost some of their edginess, Crockett said.

“You’ve got this constant game of cat and mouse, of youth culture and these companies. That lifecycle just gets shorter and shorter and shorter,” he said.

General Mills has been selling Fruit Roll-Ups with tattoo-shaped cutouts that let children make temporary tongue tattoos. Shoe maker Nike Inc. has employed celebrity tattoo artist Mister Cartoon to design six lines of limited-edition shoes. And just this month, the glass and crystal seller Steuben Glass announced it would sell tattoo-inspired vase and crystal sculpture designs by artist Kiki Smith.

“I would certainly say it has lost most of its social stigma,” said Vince Hemingson, a writer and documentary filmmaker who runs the Vanishing Tattoo Web site. The American stereotype of tattoos being for military types has become passé, he said.

American consumers watched as rock stars of the 1980s got tattoos. Their supermodel girlfriends followed, and that, Hemingson said, made tattoos visible on the women who are seen by many as icons of beauty.

That led to the proliferation of tattoos, as seen in Pew’s survey results.

To underscore that, corporate lawyer David Kimelberg published in April a book, “INKED Inc., Tattooed Professionals,” that features photos of doctors, lawyers and other executives, first in their normal work clothes then dressed so their large-scale tattoos can be seen. Kimelberg, who lives and works in Boston, said the goal of the photos is to show how tattoos are gaining popularity in corporate America.

Noting the shifting trends, he writes: “The rest of the world is finally catching up to us.”