Power entrepreneurs eye Northwest’s waterways

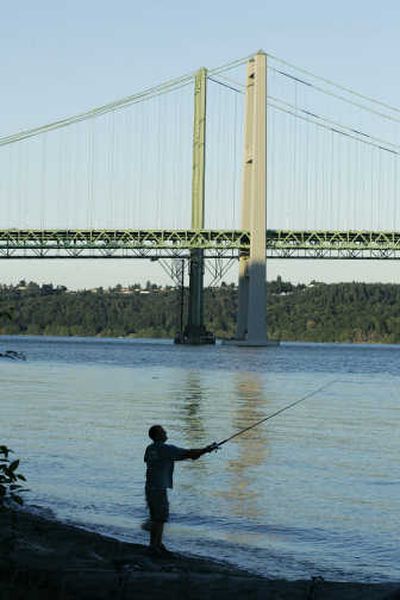

TACOMA – It’s been likened to a giant bellows or a massive fire hose, sending huge amounts of water roiling and churning between Puget Sound’s southern and northern basins with every change of the tides.

Some entrepreneurs, however, see the mile-wide channel of the Tacoma Narrows as more than a natural wonder. It’s also the next frontier of green energy.

“It’s awe-inspiring,” said Burt Hamner, chief executive of Puget Sound Tidal Power. “There is so much power out there that it boggles the mind.”

Hamner’s firm is part of an emerging industry that hopes to turn the Pacific Northwest’s wind-swept coasts and powerful tidal currents into a bountiful source of electric power.

Their pursuit is one of the big changes on the horizon for the Northwest’s hydropower industry, which faces both peril and promise from the projected effects of climate change.

On one hand, dam operators who helped build the region’s economy face a big worry: that climate change will disrupt runoff cycles, increasing tension among utilities, farmers and fish when the water supply is short.

But proponents of both old and new hydropower technologies see the chance to claim a bigger slice of the nation’s energy plans, as policy-makers look for sources of power free of greenhouse gases.

“I think we’re probably going to need to do everything when it comes to climate,” said Dan Adamson, a Washington, D.C., attorney who served on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission during the Clinton administration.

“It’s going to take a lot of different technologies to solve the problem. It’s pretty unlikely that there’s going to be one technology that’s going to be the magic bullet,” he said.

Hydropower is by far the largest renewable source of electricity in the U.S., dwarfing the contributions made by wind, solar and other green technologies.

Even so, there’s still plenty of room to grow.

The Electric Power Research Institute, an industry group, has estimated the U.S. could increase its hydropower capacity by 23,000 megawatts in the next two decades.

That’s enough power to equal nearly two dozen nuclear power plants – all without significant greenhouse gas emissions.

A good portion of that capacity could be wrested from traditional hydropower systems. For instance, the National Hydropower Association says only 2 percent of the nation’s dams currently generate electricity.

Dam operators like Tim Culbertson, general manager of the Grant County Public Utility District, say their task is wrangling more incentives from government, which has tended to favor wind development in recent years.

At the same time, Culbertson and others are looking over their shoulders at the ways climate change could alter the timing of the natural water cycle.

In a warmer climate, dam operators might face the need to spill more water for farmers or fish during a dry summer, cutting into electric generation.

A 2005 report from the Northwest Power and Conservation Council showed that by 2020, the Columbia River hydropower system could lose as much as $230 million per year due to climate change.

“We’ve lost roughly 2,000 megawatts of this hydro system for fish passage and spill issues. The concern is, do we lose more of that capacity?” Culbertson asked.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Cascade Range, utilities are lining up for a chance to launch the next generation of hydropower systems.

There are presently about 10 projects in various stages of federal permitting – including the Tacoma Power project on the Narrows – that aim to capture energy from the movement of water around Puget Sound.

Entrepreneurs and utilities also are focusing on technology that could generate power from the undulations of ocean waves.

In Oregon, a British Columbia-based company called Finavera Renewables is about to test one such system based on a floating buoy.

Conservation concerns apply here as well.

The technology is still in the experimental stage, but environmentalists such as People for Puget Sound’s Kathy Fletcher worry that large arrays of electric turbines could harm threatened killer whales, salmon and other species.

“For a lot of reasons, including protection of Puget Sound, we need to develop clean energy,” Fletcher said. “But it would just be unfortunate if we do that at the expense of Puget Sound.”

Developers say those concerns aren’t falling on deaf ears. Hamner, who is working with Tacoma Power to study the Narrows project, says new hydro technologies will only get off the ground in the Northwest if environmental worries are satisfied.

“The bottom line is, the power’s out there. But it’s got to be developed in an environmentally sustainable fashion,” he said. “We believe that is absolutely the core of our being.”