15-year-old ballplayer is all heart

Teen with rare medical problems stands out as a teammate, too

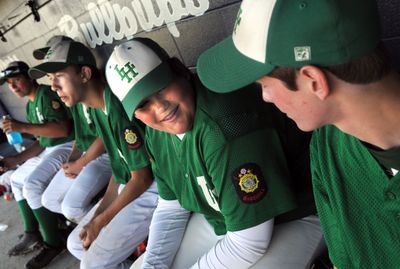

Tyler Whitehead-Edmundson sits in a shaded dugout, his eyes glued to the dusty ball field in front of him.

Shells of barbecue-flavored sunflower seeds litter the Gatorade-soaked grass around him.

Tyler, 15, is serene and cool, a man of few words, which makes him stand out in a dugout of teenage boys gibing skinny teammates and dodging insults of a “you are soo into Pokemon” nature.

Tyler is watching the sport he’s played since kindergarten. It’s the only sport he can play.

When Tyler was 4 months old, doctors discovered a heart murmur, believed to be a ventrical septal defect. When Tyler was 4 years old, a cardiologist determined that Tyler didn’t have VSD but that a ridge had formed below his aortic valve. On a mild, moderate or severe heart condition scale, Tyler was two years past severe at the time of the discovery. That’s when he underwent open-heart surgery.Now, two surgeries, two bouts of pericarditis, one bout of endocarditis (which required a six-week intravenous antibiotic therapy), and numerous infections later, Tyler is pacing back and forth next to the dirty bag under his charge, first base. A replacement valve is pumping his blood, a result of a Ross-Kono procedure performed in 2005.

During that surgery, his own pulmonary valve replaced his diseased aortic valve, and a donor pulmonary valve was inserted in place. Complications during the surgery required a coronary artery bypass. Tyler is one of very few children in the world who’ve undergone that procedure.

The Lakeside High School teen is repeatedly a one in 1,000 or one in 1 million kid, said his mom, Robin Frank, 36, while recounting a laundry list of rare past infections.

“The miracle of all of it is Tyler is an amazing human being,” she said. “And I don’t just say that because I’m his mom. … He has every right to be angry and spiteful, and he’s not.”

Tyler said he’s a typical 15-year-old who likes to play video games and paintball, hang out with friends and ride personal watercraft.

With his teammates packed on the bench around him, Tyler fusses with the Rawlings leather glove in his lap and shoots seed remnants out of his mouth.

A teammate mocks Tyler’s relaxed position – leaned forward, elbows on his legs and hands draped between them.

“You’re gonna be front-page news and you’re sitting like this,” the teammate says, hunching forward.

“Because I’m watching the game,” Tyler replies calmly, a smile creeping across his face, displaying the bright blue bands on his braces.

Tyler said everyone assumes he’s a normal kid until they notice the 6-foot teen hasn’t tried out for things like the Lakeside High School football team.

“When they figure out, they say, ‘I never would have guessed’ and that’s what I like,” he said. “I don’t want to tell anyone unless I have to. I don’t want to be treated differently.”

However, Tyler has an internal radar; he is very aware of his limitations, Frank said.

“I can’t do what everyone else does,” he said. “My body will start telling me ‘no’ when other kids are still going.”

His inability to engage in rough physical contact or lift heavy weight precludes him from playing football or wrestling, so he manages those teams at school.

“I think it’s cool. If he can’t do it, get as close to it as you can,” said his teammate, Bryan Jennings, 15.

“With everything that he has been through, nothing can kill his spirit,” said Tyler’s dad, Deric Edmundson, 36, in an e-mail. “He stays positive, focused and motivated. He didn’t let it get him down when he was told he couldn’t play certain sports. Instead, he found ways to contribute his time and talents to the team, and they greatly value him.”

Frank said while Tyler’s condition warrants extra worry, she would do Tyler a disservice by treating him differently from her other child, Samantha, 5.

“Sometimes it scares me to death to let him go do these things,” she said. “But what’s the point of saving his life if he can’t live it?”

Tyler said he appreciates the fair treatment from his summer baseball coach, Bruce Holbert, who expects Tyler to make plays and critiques him when he doesn’t.

“He gives me a chance to play and show off what I can do when other coaches have held me back,” Tyler said.

While first base is the only position Tyler can play comfortably, he also bats and practices with his teammates.

“He’s the kind of kid who’s rock solid,” Holbert said. “He’s not the best player, but we would sure miss him if he wasn’t around.”

On the field, dressed in his emerald green jersey and bleach-white pants, Tyler growls out “atta kids” and reassuredly taps the chest of a scolded teammate. He squats down toward the diamond, glove in position, his cheeks flushed from the sun. Meanwhile his teammates on the bench discuss “T.W.”

“He’s humble and funny and never puts you down,” said close friend, Ryan Gunderson, 15.

Tyler gave him the nickname “Big Sexy,” which he calls out to make Gunderson laugh when he’s pitching.

“He’s really cool, and he’s always involved in things,” said Colby Dvorak, 15.

Everyone makes it clear Tyler is an “incredible human being” who got dealt a bad deck of cards. Frank said although she wishes she could bear his burden or shield him from it, she can’t.

“I’ve told Tyler, when we’ve both been in tears, this is not a choice. We don’t have a choice. We have to do it.”

Tyler still has a severe blood clotting disorder. Due to the turbulence in his heart, platelets are destroyed as blood flows through. His donor pulmonary valve, which is prone to calcification, is starting to fail, Frank said, so he likely will have another surgery next summer.

Meanwhile, Tyler keeps living his life. Earlier this summer he went to Oklahoma to play in the world’s largest paintball game.

“I want Tyler to have exactly what he wants,” Frank said of her hopes for her firstborn. “I want him to continue to be the person that he is.”

Tyler said he plans to move to New York City after high school, attend culinary school and become a chef. He also plans to get a tattoo – a heart with scars that reads, “For every scar there’s a story.”

“I try to make the best out of life even though I have a bad ticker,” he said.