At the end of a long road

Chrysler’s plunge into bankruptcy closes the doors on a dealer that stayed in business for four generations

HOBART, Ind. – At the end of the 81-year marriage, the Isaksons said goodbye by turning off the lights. The partnership was over. The Chrysler sign went dark. It was an unceremonious finale to a four-generation bond between one family and one company, but it was not a surprise. Rob Isakson had known for weeks his dealership was on a Chrysler hit list – the cuts were part of the troubled automaker’s survival strategy. Still, when the moment arrived, he did not go gently into the night.

“It hurts,” he says. “How do you put into words 81 years of your family’s blood, sweat and tears? How many times did my father miss some family event … because the business came first? And all of it is for nothing now.”

It has been a wrenching few weeks, beginning with Chrysler’s notification in mid-May that the family was losing its franchise. The word came in a form letter. “How insensitive is that?” Isakson asks.

Then came futile efforts – through calls and e-mails – to find why they were being dropped, even though they say their sales were better than some dealers that survived.

Last week, a judge ruled for Chrysler: The bankrupt company, having sold most of its assets to Fiat SpA, the Italian automaker, could trim about a quarter of its dealer franchises.

Isakson Motor Sales was among the dealers to go. And thus ended a proud family history.

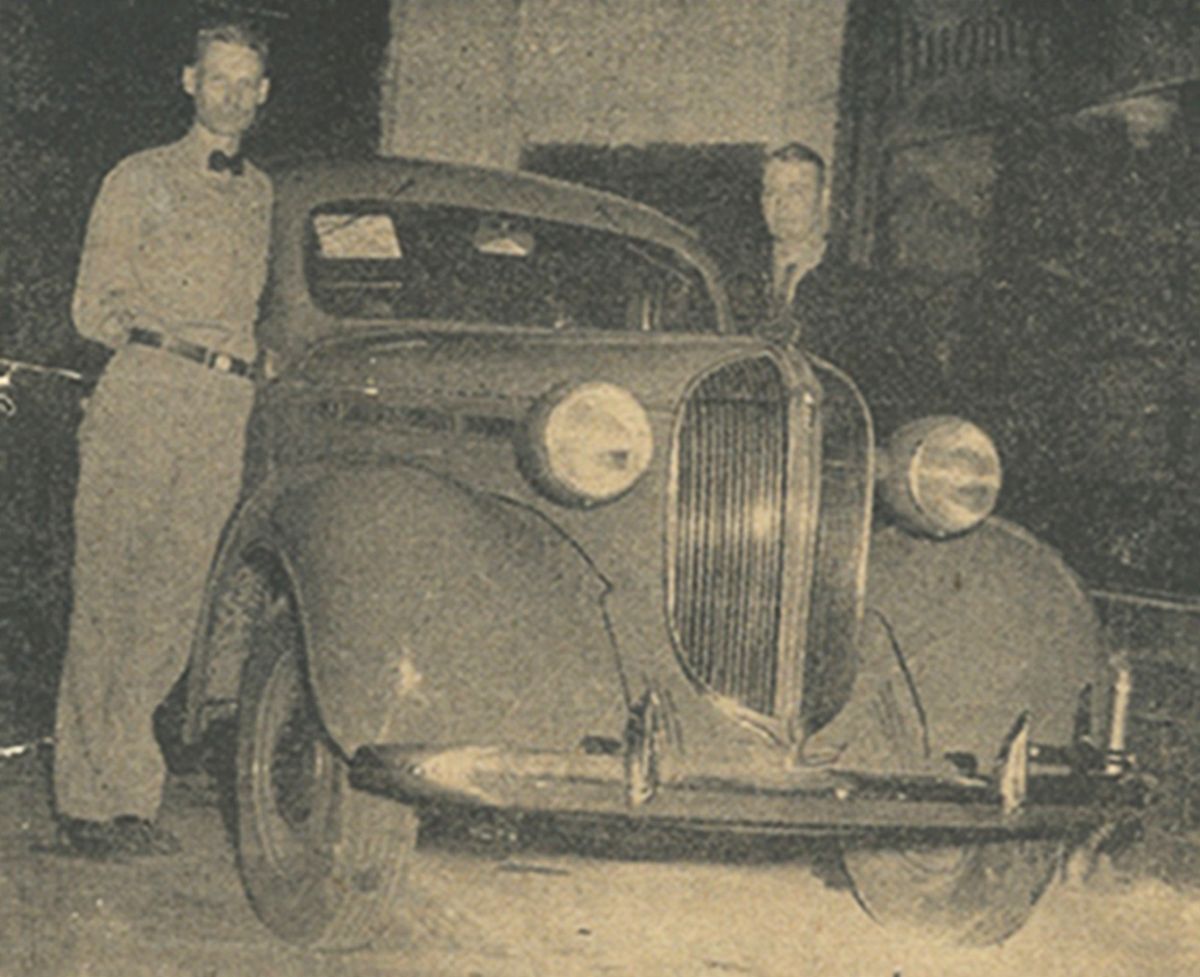

Their ties to Chrysler go back to 1928 when two Isakson brothers who were farmers invested $5,000 in an exciting new venture: the DeSoto. They opened a showroom, in the heart of what once was booming steel country, at an auspicious-sounding intersection – Front and Center.

Over nine decades, the names of the cars changed, but the name of the dealership did not. It was the Isaksons. Clarence and Walter. Bill. Rob. Eric and Steve.

Father to son, father to son, selling cars and handing over the keys to one, two, even three generations of customers, making a go of it even in the leanest years.

“How many businesses survive their first five years, or the next five?” Rob Isakson asks, huddled in his office with his 83-year-old father, Bill, and his two sons. “We survived 81 years of ups and downs in this industry. … .”

“And now,” he pauses, “we’re surviving but Chrysler says we’re not worth keeping.”

“Am I angry?” he asks, then quickly answers. “You’re darn right I am.”

GM and Chrysler, once symbols of America’s industrial might, filed for bankruptcy. And as part of their get-small strategies, they decided to shrink the number of dealers.

Chrysler released its list first. Hundreds of dealers objected, but a bankruptcy judge approved the automaker’s plan to drop 789 U.S. dealerships. (GM eventually expects to shed about 40 percent of its 6,000-dealer network.)

The Isaksons – who sell only Chryslers and Dodges – say they can understand cuts. But why punish them? Their sales, they say, have been good (about 205 new cars, 150 used in 2008). They point out they’ve received high marks from customers.

And as far as being a burden, Rob Isakson says that’s ridiculous.

“We buy our own cars, every tool … every part,” he says. “What are we doing that’s costing Chrysler money? We’re doing nothing. All we’re doing is creating more market for them. What’s wrong with that?”

The dealers aren’t the only ones who will be taking a hit. The National Automobile Dealers Association estimates the GM and Chrysler dealer closings will wipe out more than 100,000 jobs; the average wage is between $45,000 and $55,000 a year.

Then there’s the domino effect.

“How many insurance company salespeople are going to be gone?” Rob Isakson asks. “How many tire stores are going to be closed? How many barber shops, how many restaurants? There’s going to be a ripple effect.”

Add to that taxes and the gaping holes left by dealers – many of them family-owned businesses – who have been mainstays in their communities.

“They’re one of the few vestiges of what used to be Main Street America where businesses are locally owned and operated,” says John McEleney, chairman of the dealers association. “They’re the fabric of the community.”

“We’re the people the community goes to for support for Little League, for high school athletics, the fund drives for hospitals and colleges,” he says. “If GM closes a plant, it’s a huge thing. But closing 2,100 dealers is almost like closing 2,100 plants in some of these communities.”