Petition drive hires firm

Disincorporation group pays for help to meet deadline

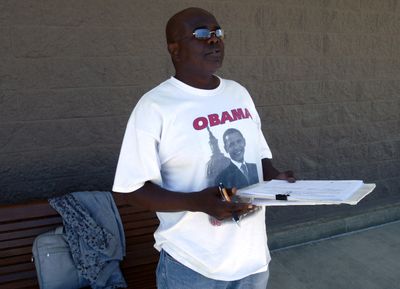

Backers of a drive to disincorporate Spokane Valley have turned to paid signature gatherers, including at least one with a dubious grasp of the issues.

A young man stationed in front of the Trading Co. store at Sprague Avenue and McDonald Road last week asked a Spokesman-Review reporter whether he wanted to sign a petition to merge Spokane Valley with Spokane – just about the last thing most disincorporation supporters would want.

“Oh, my God,” disincorporation organizer Sally Jackson gasped.

Jackson, chairwoman of Citizens for Disincorporation, said she had hoped to use only volunteers “because everybody who goes out knows what he’s doing and is dedicated to it.” But developer Dean Grafos offered to hire some signature gatherers to supplement the volunteers, she said.

Grafos, owner of Grafos Investments, declined to reveal the signature-gathering firm, the number of employees assigned to the job, the amount being paid or whether the workers are paid by the hour or by the signature.

He said members of Friends of Spokane Valley, a group he helped establish, have hired a “handful” of signature gatherers as an in-kind contribution to Citizens for Disincorporation.

Friends of Spokane Valley supports disincorporation because of dissatisfaction with the city’s proposed Sprague-Appleway Revitalization Plan. Members object to the plan’s “stealth rezoning, government taking and bureaucratic power grab,” Grafos said.

Jackson and Citizens for Disincorporation Treasurer Dorothy Dieni said they had no details on the professional signature gatherers, although their group will be required to report the contribution to the state Public Disclosure Commission.

In its latest monthly report on May 5, Citizens for Disincorporation reported collecting $3,471 and spending $1,614 since the organization registered with the disclosure commission on Feb. 24.

Grafos said the signature gatherer who talked about merging Spokane Valley with the city of Spokane was in his first day on the job and had confused Spokane with Spokane County. Disincorporation proponents want control of Spokane Valley, which was incorporated in 2003, to revert to the Spokane County government.

“We have that confusion cleared up now,” Grafos said.

That wasn’t the employee’s only incorrect information, though. And some of his financial claims were subjective at best.

Disincorporation would save Spokane Valley taxpayers $91.7 million, he told another Spokesman-Review reporter whose signature he solicited.

The disincorporation employee proffered a laminated sheet of talking points that said the city’s 2008 budget was almost $87 million and “essential services” from Spokane County amounted to $18.5 million.

“What did you get for the other $68 million?” the sheet asked.

So what accounts for the promised $91.7 million saving?

“I’m not really sure,” the youthful signature gatherer responded. “I’m still learning stuff offline. It’s Initiative 1094 for any further information that you’d like to find out. It’s on the secretary of state’s Web site, I believe. That’s where I got this from; it was from that Web site.”

Trouble is, the secretary of state provides no such information.

“A local issue would not appear anywhere on our Web site,” said David Ammons, the secretary of state’s communications director.

What’s more, there is no Initiative 1094. The highest number that has been assigned is 1050.

The disincorporation drive has no official name because it has had no official action. Unlike statewide initiatives that have to be registered with the secretary of state, a disincorporation petition gets no government review until it is submitted to the county auditor for signature verification.

Jackson and Grafos defended some of the financial information the signature gatherer presented, but said they had no idea how he came up with “Initiative 1094.”

Mayor Rich Munson said he couldn’t rebut the signature gatherer’s budget information because it “simply didn’t make any sense to me,” but taxpayers are getting their money’s worth.

He said taxes that used to go to Spokane County now are focused on Spokane Valley, and residents are represented by seven City Council members instead of one county commissioner.

Residents have their own park system, a legal department focused on their interests and a street department whose only duty is Spokane Valley streets, Munson said. Also, he said, council members represent the city on 17 boards and commissions, including the Spokane Transit Authority, the Growth Management Act Steering Committee and the Spokane Regional Health District.

With regard to disincorporation, Munson said, “It does speak to the grassroots aspect of the project when you go out and hire somebody.”

However, Ammons said almost all statewide initiative drives use professional signature gatherers. Otherwise, it would be “almost impossible” to get a measure on the ballot because signatures must equal 8 percent of the turnout in the previous general election.

For a disincorporation petition, the bar rises to 50 percent. That worked out to 24,012 when the Spokane Valley drive got under way in February.

Grafos said he is convinced most Spokane Valley residents want to vote on the issue, but “getting over 24,000 signatures within a very short time frame requires a multifaceted approach.”

There is no deadline for filing the petition at the county auditor’s office, but signatures more than 6 months old won’t be counted.

The employee gathering signatures for “Initiative 1094” said disincorporation supporters have a goal of collecting 30,000 signatures in 45 days. That’s true, Grafos said.

The employee also said 5,000 signatures had been gathered by May 14.

“That’s just five days’ work,” he said, overlooking weeks of door-to-door canvassing by volunteers. “We average about 1,000 a day.”

Enthusiasm for the city was lackluster when residents created it. Only 51.4 percent of voters supported incorporation in May 2002. Three previous votes for Valleywide incorporation and two proposals for smaller cities got no more than 44.3 percent support.

Jackson has said about 10,000 residents signed a disincorporation petition in 2005, when 23,865 signatures were needed. It was the second disincorporation drive to end in failure, and none of the petitions was submitted to the county auditor’s office.

Government officials won’t tell disincorporation advocates whether they followed the right procedures until they turn in a petition.

“We would not evaluate the language beforehand,” Spokane County Auditor Vicky Dalton said. “The law does not give us that authority. It’s up to the grassroots effort to make sure everything is proper.”

Dalton said disincorporation petitions are rare in Washington, and Spokane County has never received one. The last disincorporation in Washington was for the town of Elberton, in Whitman County, in 1965.

That was before state Boundary Review Boards were created and given a role in reviewing disincorporation petitions.

Dalton said she and other public officials are still studying the procedures they’ll have to follow if they receive a petition.

Susan Winchell, director of the state Boundary Review Board for Spokane County, said some details are murky, but her agency’s five-member board will decide whether to allow a disincorporation election if a valid petition is filed.

Among other things, the board would have to find that disincorporation would be consistent with the state Growth Management Act. Winchell said the act states that cities generally are best equipped to provide urban services, but doesn’t clearly say that urban areas should be governed by cities.

Board members also would have to consider the effect disincorporation would have on other units of government. A decision could take up to four months.

“There are all kinds of things they balance when they make a decision,” Winchell said.

The Boundary Review Board has two members appointed by the governor, one appointed by county commissioners, one appointed by mayors in Spokane County and one appointed by fire, water and similar special-purpose districts.